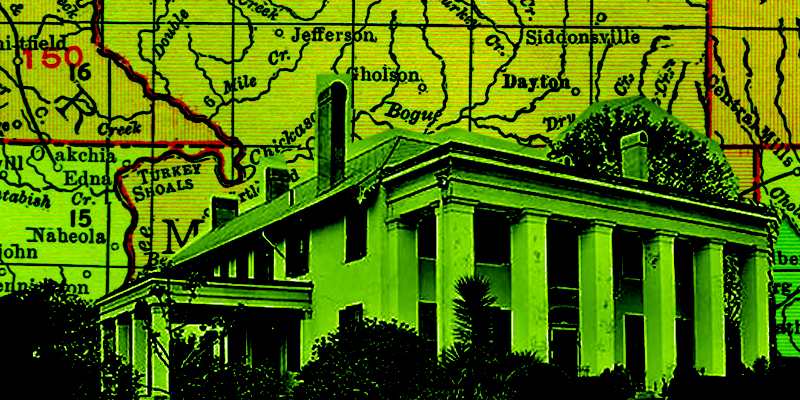

1. The 1934 Extinguishing of the Frank Clements and Elsie Hildreth Smith Family

The coroner declared that there was no evidence that the house had been forcibly entered, but added that the investigation showed that the Smiths frequently did not lock doors and windows at night.—“Alabama Banker and Family Slain—Couple Were of Leading Families,” New York Times, November 26, 1934

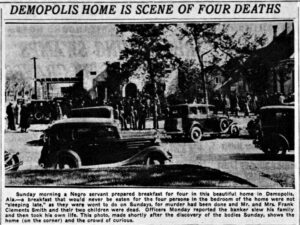

As day began to dawn on Sunday morning, November 25, 1934 in Demopolis, a quiet little Alabama town of just over four thousand souls situated in rural Marengo County at the confluence of the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers in the heart of the state’s old plantation belt, Gertrude Robertson, cook to Frank Clements Smith, cashier at Demopolis’ Commercial National Bank, his wife, Elsie Hildreth Smith, and their two young children Frank and Sabra, entered the Smith house—as she had for over a year now, ever since Clements and Elsie had wed on another Sunday morning a year and seven weeks ago on October 8, 1933—to make the family’s breakfast. Having prepared the meal and set the table, Gertrude called for the family to come and eat. Receiving no answer in the strangely silent house, the cook knocked and entered the Smiths’ master bedroom. There she confronted unimaginable horror, what the Demopolis Times four days later pronounced “[u]ndoubtedly the most shocking tragedy that has happened in the city of Demopolis.”

Gertrude Robertson, a twenty-eight-year-old black woman who a decade earlier had born a son, Nathan, knew very personally the tragedy of the death of a child, for her boy had passed away earlier that year in July. Yet the Smiths’ cook could not have been prepared for the nightmarish tableaux which faced her now, in that grim bedroom. So appalling was her brief seconds’ sight of the occupants that she fled panic-stricken from the scene to the home, directly across the street, of the widowed Hannah Koch and her bookkeeper son Isidore, members of Demopolis’ once significant Jewish community, which numbered around 150 people at the time. Desperately beseeched by Gertrude, Isidore Koch entered the Smiths’ master bedroom and there found the entire family—husband, wife, toddler son and infant daughter—gruesomely slain, each and every one of them brutally shot to death.

Clad in his pajamas, thirty-six-year-old Clements Smith lay on the floor by his and his wife’s bed, his forehead grazed by a bullet and a powder-scorched hole by his right ear. Thirty-three-year-old Elsie, fully clothed, rested across the foot of the bed with two bullet wounds to her chest. Her hands were crossed reposefully over her disfigured breasts, as if she were a stone sarcophagus effigy slumbering timelessly in a mediaeval church. Elsie’s three-year-old son by a prior marriage, Frank Alkire, who normally slept in his own room, lay on the bed beside his mother, dead like his stepfather from a shot to the head, while the couple’s infant daughter, Sabra, just six weeks old, lay tucked snugly in her netted crib, shot through her mouth.

Police found two pistols in the bedroom. Under the bed was an old style “lemon squeezer” .32 short revolver, so named for the grip safety in its back strap, which made it necessary to firmly grasp the gun while depressing the safety lever to fire it. From the lemon squeezer three lead bullets had been fired. On a shelf in the closet there was also a blood-spattered, pearl-handled automatic pistol, which Clements had only recently purchased. From this weapon four steel-jacketed cartridges had been fired. Elsie, her son and Sabra had been killed by steel jacketed cartridges, Clements by a lead bullet. Scattered around the room were four steel-jacketed cartridges and a single lead bullet.

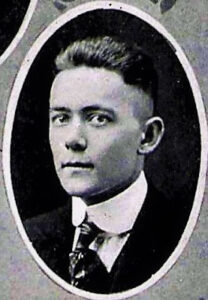

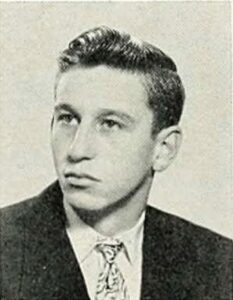

Clements Smith

Clements Smith

Coroner Cedric C. F. Hickman, professionally affiliated with the B. J. Rosenbush Undertaking Company and Furniture Store in Demopolis, soon arrived to take charge of the house and bodies. By this time word of the murders had spread like fire through the small town and hundreds of people, foregoing church services, had gathered round the Smiths’ small but fashionable Spanish Revival home to witness the comings and goings of law enforcement and exchange thrillingly bloodcurdling speculations about just what horrors had taken place there. Sheriff Sam Drinkard, who appears to have rotated in and out of the county sheriff’s office with his elder brother Dwight Moody Drinkard, arrived next from the county seat of Linden, a little town of under one thousand inhabitants located seventeen miles to the south of Demopolis, to take charge of the murder investigation. The previous year both of the Drinkard brothers had been ignominiously hauled into federal court on a charge of conspiracy to violate the soon-to-be repealed National Prohibition Act by accepting bribes from Vester Ward, a farmer and moonshiner in the small town of Thomaston, eleven miles east of Linden; but they had been found not guilty and their reputations as lawmen evidently remained good, at least within the confines of Marengo County.

Upon his arrival in Demopolis, Sam Drinkard summoned Officer George Burton Porter, an ambitious and keen-eyed young fingerprint identification expert from the city of Selma, a comparative metropolis of over 18,000 inhabitants located sixty miles to the east of Demopolis in neighboring Dallas County, to take the pistols back to Selma for testing. Officer Porter, who on his own initiative six years earlier had started Selma’s identification bureau literally from his desk drawer, was familiar with the Drinkard brothers, having worked with then Sheriff Moody Drinkard in 1929 on another brutal Marengo County murder case, when he had been called in to take fingerprints from the bloody axe used to bludgeon to death seventy-six-year-old James Richmond Moss, storekeeper and postmaster at the village of Hugo, located between Linden and Thomaston. Moody Drinkard had vowed then that to find the slayer of old Jim Moss he would get Officer Porter to “fingerprint every person in the county if necessary.” In reality, however, he locked up a dozen or more black people, ultimately securing a confession from a pair of Birmingham men who had come down to Marengo to visit some of their kinfolk.

As they had five years earlier in the Moss murder case, Marengo cops initially looked for the culprit of the mass shooting at the Smith home among the county’s large black population. They quickly arrested and questioned John Robertson, the seventy-four-year-old yardman at the Smith house (it is unclear whether he was related to Gertrude), but soon set him free. The initial theory that the Smiths had been robbed and murdered by a home intruder dissolved after a wristwatch and rings on Clements and Elsie’s bodies, along with other assorted valuables, were found untouched in the house. Also quickly exonerated was Gertrude, who resided quietly and blamelessly with her elderly grandparents, James and Ella Robertson, at their humble place on Arcola Street, a couple of miles away from the Smiths’ fancy residence on South Cedar Avenue. Thus after several days the case remained officially unsolved, as newspapers around the country blazed horrific headlines about the affair (Demopolis Shooting Wipes Out Family).

The Smiths of Bluff Hall

The slain Frank Clements Smith was the son of the late Andrew Reid Smith, in life an electric company executive and president of the Demopolis Commercial National Bank, and his wife Clara Estelle Clements Smith. When they married in 1893, Andrew and Clara were socially prominent natives of the city of Tuscaloosa, home of the University of Alabama, located sixty miles north of Demopolis. Clara, “one of the most brilliant ornaments of Tuscaloosa society,” was a daughter of attorney Rufus Hargrove Clements and granddaughter of Hardy Clements, said to have been the wealthiest planter in Tuscaloosa County before the Civil War, owner of a thousand slaves, twenty thousand acres of land and declared personal wealth in 1860 of around nine million dollars (in modern worth). Seven years after Andrew and Clara moved to Demopolis at the turn of the century, the couple purchased Bluff Hall, an imposing, white-columned antebellum mansion overlooking the Tombigbee River that originally had been owned by planter-politician Francis Strother Lyon and his wife Sarah Serena Glover Lyon, a sister of Williamson Allen Glover of Rosemount plantation in neighboring Greene County, one of the great architectural showpieces of the South.

Bluff Hall

Bluff Hall

At Bluff Hall the socially ambitious Clara established herself as Demopolis’ reigning hostess, organizing such festive occasions as the 1915 fall harvest celebration of that “unique and exclusive dinner club,” peculiarly indigenous to the town on the Tombigbee, known as Ye Kanterberry Klan—not to be confused, of course, with the Ku Klux Klan, which had been revived, coincidentally (or not), that same year. The society page editor at the Demopolis Times painted this pretty, if precious, picture of the lavish event (to which I can but say, Ye Gods!):

One of the most brilliant social functions which has taken place this season was the meeting and banquet of Ye Kanterberry Klan which occurred on ye night of the eighteenth of November at Bluff Hall, the magnificent home of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Reid Smith….From seven to eight Ye Klan held a reception of good fellowship…after which hour ye banquet was announced and the guests were ushered into ye banquet hall….Immediately following the dinner….Andrew Reid Smith was unanimously selected [Konsort] and escorted in pomp to ye throne by Ye Klan and crowned in stately grace by Ye Kommander.

Aside from its gracious parties, Bluff Hall was noted for its lovely collection of Japanese curios, which had been sent to Clara by her wealthy brother Julius Morgan Clements, a mining geologist and engineer of international repute and a noted Asiatic traveler who was fluent in a dozen languages. It was at beautiful Bluff Hall that Andrew and Clara’s boys—Frank Clements Smith and his two brothers, Fenton Reid Smith and Charles Singleton Smith, all three of them short, slim, blonde and blue-eyed—grew to manhood with gilded prospects seemingly glittering enticingly before them. Although Andrew died from heart disease at the age of sixty-three in 1932, Clara still resided at Bluff Hall two years after her husband’s demise, when her middle son and his family died so horrifically within a five minutes’ drive from the mansion. On that other Sunday morning on October 8, 1933 when Clements had wed Elsie—“very quietly, with only relatives present,” the Demopolis Times reported—the ceremony had taken place at Bluff Hall with far less ostentation than had that Qwyte Kolorful celebration of Ye Kanterberry Klan. On the occasion of her second son’s quiet wedding Clara decorated the stately old southern home with “vases of dahlias, roses and other cut flowers” and the bride had “carried pink rose buds and lilies of the valley.” What flowers Clara placed on Elsie’s grave, and the graves of her son and grandchildren, after their gruesome violent deaths a year and seven weeks later went unreported.

It was also at Bluff Hall on the Monday morning after the murders that a short funeral service was conducted on behalf of the fallen family. Two caskets were provided for the four family members, one for Elsie and her son Frank, and one for Clements and little Sabra, who had barely had a chance to live before she died. From Bluff Hall a funeral cortege made its somber way sixty miles northward to the city of Tuscaloosa, where, after another service at Trinity Episcopal Church, the dead were interred in the old family plot at Evergreen Cemetery.

Bluff Hall

Bluff Hall

Newspapers divulged that the late Frank and Elsie Smith had been “considered a very devoted couple by all who knew them” and that both of them had “seemed to idolize their children.” Man and wife alike were “great favorites in the circle of the younger married set” in Demopolis and Clements in particular was deemed to have a “gentle and pleasant disposition that makes friends.” These bouquets of praise thrown upon the dead couple only seemed to make their murders, and those of their children, yet more mystifying.

Officer Porter and the Incurious Inquest

At the coroner’s hearing held a couple of days after the discovery of the dead family, it was revealed that Clements and Elsie had spent Saturday evening at the home of the singularly named Mem Creagh Webb, Jr. and his wife Frances, another locally esteemed young couple with two small children of their own, leaving Frank and Sabra in the care of the redoubtable Gertrude Robertson. According to Chief William Bedford Davis of the Demopolis police, “the couple had quarreled at a party earlier in the night,” by which, presumably, he meant the get-together at the Webbs’ place. Around 9:30 p.m., the Smiths left the Webbs’ house, located on West Capitol Street just down from the old John C. Webb mansion, to drop off at the Demopolis Inn (Modern in Every Way), just two minutes away on West Washington Street, forty-three-year-old Austin Thomas Ars, a tall, brown-haired, gray-eyed accountant and Great War veteran who had been married for fifteen years but had no children. Clements and Elsie then returned to the Webbs’ house, where they remained until shortly after ten, when they left for home.

Around 10:30, Clements entered his house and immediately dismissed Gertrude, informing her that “his wife would be in in a few minutes” and that he would give the infant Sabra her bottle of formula. Some in town had deemed this an odd circumstance, but Police Chief Davis, choosing his words with evident care, speculated that “Mrs. Smith and her husband might have preferred that the cook not see her on her return home and that she might have remained in one of the front rooms of the house as the cook took her departure for the night.” On a table police found a liquor bottle and two glasses containing remnants of whiskey.

“What followed is problematical,” reported the Demopolis Times, but perhaps things were not so challenging at the Demopolis newspaper wanted its readers to believe. Admittedly, Coroner Cedric Hickman had clouded the matter by maintaining there was a “slight chance” that “an outsider might have been responsible for all the deaths.” Coroner Hickman—who belying his sober profession as a mortician, conducted a Demopolis dance orchestra, served as music director of the First Baptist Church and was celebrated, among the town’s white population anyway, for his performance in blackface minstrel shows (“His monologue with a broom will be remembered by all who saw it,” his 1961 obituary avowed.)—doubtlessly did not want to alienate potential future customers in Demopolis society and thereby made sure to handle the hearing with extreme discretion. However, according to the Selma Times-Journal, which was rather more forthcoming than the Demopolis Times, the Selma fingerprint man George Porter, the lead expert at the hearing, chattily confided to reporters that Clements had shot both himself and his family. Both of the discharged pistols in the bedroom, he explained, bore Clements’ fingerprints. Newsmen naturally pricked up their ears at this. “Frank C. Smith, Demopolis banker, snuffed out the lives of his wife and babies with a fusillade of shots and then turned a gun on himself—that is the theory Fingerprint Expert Porter, of Selma, will substantiate with scientific evidence before a coroner’s jury Tuesday,” was the blunt first paragraph revelation in another nearby newspaper, the Clarke County Democrat, located in the town of Grove Hill, sixty miles south of Demopolis.

Voluble Officer Porter begged to differ with Coroner Hickman about the prospect of a home invader having been the culprit of the crimes, discounting the possibility entirely. He theorized, both on the stand and to the press, that after shooting his wife and children with the automatic, which he had carefully replaced on a shelf in the closet, Clements had shot himself with the old revolver, but had succeeded only in grazing his forehead with the bullet and stunning himself for a time. “The weapon used, a small caliber revolver with a ‘lemon squeeze’ handle that had to be pressed hard to fire the pistol, caused him to miss a vital spot,” Porter speculated. He believed that Clements, after lying in a stupor on the floor for an hour and a half, revived and finished the grim job which he had started, fatally discharging a bullet into his brain from the revolver, which fell under the bed. With ghoulish implication Porter added that at some point Elsie’s body had been “tampered with” after she had been shot, presumably by Clements. “There were two bullet wounds, one in each breast,” the cop elaborated, “and [Mrs. Smith’s] hands had been placed over each wound and her elbows pushed neatly down beside her.”

Notwithstanding Officer Porter’s opinions—which were substantiated at the hearing by Dr. Claude Nicholson Lacey, the Demopolis physician who had examined the bodies—the six-man coroner’s jury, likely influenced by or simply sharing Coroner Hickman’s hope of pinning the crime on a home invader, balked at placing responsibility for the murders explicitly on Clements Smith’s shoulders. As Police Chief Davis dogmatically insisted, the Smiths “just weren’t the kind of people for that.” Instead the jury, after listening to over four hours of testimony from Officer Porter, Dr. Lacey, Sheriff Drinkard, Chief Davis, Gertrude Robertson, the Creaghs and others, merely allowed what seemed the bare, bald facts at this point: that Elsie, her son Frank and her daughter Sabra had been murdered around three a.m. and that Clements had committed suicide an hour and a half later around four-thirty.

We Know Who Did It—But Why?

Since the jury in deference to the denizens of Bluff Hall had refused to assign responsibility for the murders of Elsie and her children, they naturally could not answer, or even broach, the question of why they had been murdered. If we assume the obvious, that Clements was the murderer, we are left to answer for ourselves the question of why a devoted husband and father who loved his wife and adored his children would so heinously have slaughtered them and then himself. Embezzlement is ruled out, for Demopolis police examined Clements’ books at the bank and found them to be, in the words of Police Chief Davis, “in good shape.”

Since the jury in deference to the denizens of Bluff Hall had refused to assign responsibility for the murders of Elsie and her children, they naturally could not answer, or even broach, the question of why they had been murdered.A year after the tragedy Clement Eaton, a distinguished historian of the American South who was then chairman of the History Department at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania (apparently he was no relation to the Smith family), visited Demopolis, where he toured the town’s fabled old antebellum mansions, Gaineswood and Bluff Hall, and had his ear filled with lurid details about the recent ghastly killings. “I was told that the inheritor of Bluff Hall married a divorcee—one night he and she returned from a wild party, and later he found her untrue to him & shot her, her two children & himself,” Eaton confided that night in his diary, concluding sententiously: “In this beautiful home an unlovely home life must have existed.” Despite the fact that Eaton got some of the detail wrong—presumably none of the murders had been committed at Bluff Hall, where Clara still lived with her youngest son, Singleton Smith, and his wife and son—the whispers which the professor heard of a “wild party” and amatory unfaithfulness provide us with motive for Clements’ seemingly inexplicable act, in this lurid light one of the most extreme fury and despair. As the Linden Democrat-Reporter bluntly put it: “[I]t is believed that jealousy drove Mr. Smith to the breaking point.”

What had happened between Clements and Elsie to prompt them to quarrel on that fateful Saturday night in 1934? Had the Webbs held a “bottle party” with some of their friends? What had occurred on the Smiths’ short drive with Austin Ars to the Demopolis Inn (and back)? Why had it taken the Smiths nearly half an hour to reach their home from the Webbs’ place on Capitol Street? (This should have been a four or five minutes’ drive at most.) And where was Elsie when Clements confronted Gertrude at their home? Was she inebriated, as Chief Davis seemingly implied, and unfit to be seen by the help? Was she even present at the house at all? In the findings of the coroner’s jury we have no solid evidence as to Elsie’s whereabouts between her departure with Clements from the Webbs’ house around 10:00 in the evening and her death, presumably in the bedroom of her own home, around 1:30 in the morning. In the astounding dénouement to a Golden Age detective novel—the sort of book so popular with Thirties fiction readers—it might have been revealed that Elsie actually had been done in by her mother-in-law Clara at Bluff Hall, which lay just a minutes’ drive around the corner from the Webbs’ place, with Clements serving as Clara’s fall guy.

The home in which the murders were committed.

The home in which the murders were committed.

Elsie Smith was, as Clement Eaton had noted, a divorcee—indeed she had been twice divorced. This is a point of interest, I think, whether or not one agrees with Clement Eaton and his Demopolis gossips that the dread word divorcee deserves a connotation of moral dubiety. Certainly newspapers at the time thought this was relevant, for in banner headlines many of them—the Demopolis Times excepted—damningly included, in reference to Elsie, the dread words SHE HAD BEEN DIVORCED.

The Dubious Case of the Double Divorce

Yet as even those newspapers admitted, Elsie came from a respectable social background. “Her large family connections are of the very best, and she was quite a favorite among them” the Demopolis Times avowed of Clements’ bride. Although Elsie, the youngest of four children with three elder brothers, had been born in St. Augustine, Florida, where her father was a railroad conductor, she was descended from the Hildreth family of Jefferson, a planter village located a dozen miles southwest of Demopolis. However her mother, Willie Jefferies Alston, had died in 1910, when Elsie was just nine years old, leaving her father, Levin Hildreth, to raise the children. After World War One, Levin along with his youngest son and Elsie relocated to the mining town of Prescott in central Arizona, where he worked as a railroad brakeman. From then on it appears that his fair and fleet daughter ran footloose and fancy free.

In 1920 Elsie Hildreth was lodging separately from her father in Prescott with a druggist and his family. On December 15 of that same year, Elsie, now nineteen, at her brother’s house in Prescott married twenty-four-year-old Riverside, California native George Battles Finch, 6’2”, 170 pounds, blond-haired and blue-eyed. Elsie, whom the Prescott Weekly Journal-Miner in a notice about the wedding described as “a well-known and popular member of Prescott’s younger set,” was dressed in “a becoming brown satin gown, with hat and shoes to match.” Despite Elsie’s purported popularity, however, “only a few intimate friends were present” at the ceremony. Recalling her and Clements’ later wedding, which was conducted “very quietly, with only relatives present to witness the ceremony,” can one sense a pattern of avoidance here?

In Prescott, George Finch had superintended the Arizona Bus Company, but the new couple moved to his native Riverside in southern California, where George had accepted a position with the firm of J. W. Kemp, Cadillac dealers. Apparently Elsie left both Riverside and her husband just a few weeks later, however. Ten months after the wedding, the Prescott Weekly Journal-Miner reported tersely that “Mrs. Elsie Hildreth Finch…left [Prescott] to return to her former home in Alabama, where she will remain with relatives.” The romantic career of Elsie, who was now divorced and going by her maiden name, fades from view for most of the rest of the Roaring Twenties, although in Arizona she popped up occasionally in Prescott and Phoenix and in 1925 she wintered at the home of her brother Kent Hildreth in Palm Beach, Florida.

Franklin Tomlin Alkire

Franklin Tomlin Alkire

Four years after her winter sojourn in Florida, Elsie, now twenty-eight, was back again in Arizona, where on December 2, 1929 she wed strapping 6’1”, 190 pound, black-haired Josiah Franklin Alkire, a thirty-eight-year-old trader on the Navajo Nation reservation and son of the respected pioneer Phoenix rancher and merchant Franklin Tomlin Alkire. Like Elsie, Jay, as he was familiarly known, had been previously married and divorced. In 1931 Elsie gave birth to the couple’s son, named Frank in honor of his paternal grandfather, but the marriage had foundered by 1932, the same year in which Elsie’s father passed away. Elsie returned yet again to her relations in Marengo County, where she met and enchanted with her peculiar charms Clements Smith, a diminutive but dashing University of Alabama graduate and cashier in his late father’s bank who though in his thirties still lived with his parents at elegant Bluff Hall. Elsie briefly returned to Phoenix to obtain a divorce from Jay and then fatefully married Clements.

At UA back in 1920 the school yearbook had portrayed the handsome young Clements, a member of Alpha Tau Omega fraternity, as a dirty-blond and blue-eyed heart breaker: “How so much good-heartedness and pep can be combined in five feet four inches, has long been a wonder to us. A ‘top’ sergeant in SATC days [Student Army Training Corps] and the cause of many broken hearts and wistful glances.” Yet it appears to have been UA’s heartbreaker Clements Smith who in 1934 was mastered by his passion for his wayward wife and destroyed both himself and her, along with their innocent children.

Faded Snapshots from Some Family Albums

Bert Julius Rosenbush, Sr.

Bert Julius Rosenbush, Sr.

In 2011 the Southern Jewish Historical Society sponsored a fascinating interview with Bert Julius Rosenbush, Jr., the so-called “last Jew in Marengo County” whose father, Bert Julius Rosenbush, Sr., at the time of the extinguishing of the Clements Smith family owned a Demopolis furniture store and funeral home which employed none other than Coroner Cedric Hickman. Although he was only five years old at the time of the slayings (his sister was just two), Bert, Jr. recalled with palpable and poignant sadness that the terrible violent deaths of this attractive young family had prompted his sensitive father, who was given the mortifying task of preparing the victims for burial, to abandon the funeral business for good and all. Just five years earlier Bert., Sr. himself had been wed, to Miriam Stein, in a widely attended ceremony performed thirty-five miles to the west at the Baptist Church at the little town of Cuba in neighboring Sumter County (no synagogue was available there); and their marriage had produced much happiness in both of their lives, along with their little boy and girl.

Two years prior to the Smith murders, Bert, Sr., on his way back to Demopolis from the city of Birmingham, in his own ambulance had removed, with the assistance of his two trained nurses, the lifeless body of eighteen-year-old farmer Lawrence Daniel Garris, who had been killed when his truck overturned east of Demopolis, and prepared him for burial at his mortuary. “To forget is vain endeavor,” Lawrence’s grief-stricken parents inscribed on their dead boy’s gravestone; and, true to those words, Bert, Sr. found that he simply could not get the ghastly images of the bullet-felled Smiths—Clements, Elsie, Frank and Sabra—out of his mind:

Rosenbush: [W]hen my daddy went in the business he went to Cincinnati and became a licensed embalmer. He practiced embalming along with running the furniture store with my grandmother until a tragic accident happened here in Demopolis. After that accident…it was just such a sad affair that my daddy decided to give it up.

Interviewer: What was the accident?

Rosenbush: It was…a man killed his family and they were about the same age as [my daddy’s] family. So, he just decided…just to stick to the furniture business and give up the undertaking part.

Death seemed greedily to stalk and devour the Smith family during the Thirties and Forties. Both Clements’ elder brother, Fenton Reid Smith, and his sister-in-law likewise were taken in unexpected ways. In 1923 Fenton married Alice Portman Bright and later the couple moved to the Panama Canal Zone, where Fenton was employed as a plant manager with the General Electric Company. About eight months before Andrew Reid Smith’s own passing in 1932, his daughter-in-law Alice died from Spanish Influenza in the Canal Zone at the Gorgas Hospital (named for the famed native Alabamian disease battler William Crawford Gorgas). Nine years after his wife’s untimely death, Fenton himself perished in the Canal Zone at the age of forty-eight, when in 1943 he drowned while fishing for tarpon in the roiling waters of Gatun Spillway.

The Smith family matriarch would have been forgiven for having found it all too much to bear, but she must have had more than an inkling of danger when Clements married Elsie back in 1933, for she knew well from her own family history the menace which lurked in mésalliances. Fifteen years earlier her previously divorced brother J. Morgan Clements, the bestower of her celebrated Japanese curio collection, had made an ill-advised marriage in 1908 to a beautiful brunette double divorcee, a certain Mrs. Josephine Burley, a stenographer of ambiguous antecedents from Butte, Montana. The couple had first met four years earlier, when Josephine had immediately won the mining expert’s sympathy by tearfully confiding to him that she was contemplating suicide over some bad mining investments which she had made. “The bride was well known among a select circle of friends who felt for her the warmest friendship, as her splendid womanly nature appealed to all her knew her,” the Butte Miner put it in words that, in my eyes at least, raise several red flags, adding reassuringly, if vaguely: “She is a woman of superior mental attainment and belongs to an old southern family of revolutionary fame.”

Unfortunately, Morgan—who from his copper mines and other holdings annually earned, in modern value, an income of around half a million dollars a year, making him a tempting matrimonial mark for a sharp-eyed adventuress—found life with this most womanly of women utterly unbearable. Within a year of the wedding he left Josephine and returned to New York, providing her with monthly support of $125 ($3500 today), the equivalent of what she had earned as a stenographer before her marriage. Over the next year Josephine racked up $6000 ($170,000 today) in personal expenditures and sent a flurry of importunate and recriminatory letters to Morgan’s friends and family, including his sister Clara, in which she lengthily accused her estranged husband of myriad acts of insanity and immorality. She also claimed that Morgan had sent her to Alabama to visit Bluff Hall in order to have Clara procure her an abortion. “When a bug seeks shelter under a rotten log,” Josephine warned Morgan after he refused to return to her, “someone is going to kick that log and expose it.”

In 1910 Josephine brought a separation suit against Morgan in New York, where he then resided, requesting monthly alimony of $400 ($11,000 today)—an action which prompted her exasperated husband to counter through his lawyers that the extravagant “termagant” whom he had so foolishly married deserved not a dime more from him. While not rising to the notoriety of the recent Johnny Depp-Amber Heard defamation suit, the case of Clements v. Clements made newspaper headlines across the country over the next couple of years and was heard by famed judge John W. Goff, once characterized as “the cruelest, most sadistic judge we have had in New York this century.” Morgan’s lawyers introduced evidence of Josephine’s lies about her social background, instability and “vain, conceited, coarse, vulgar” behavior in general and they even plausibly urged that at a Phoenix, Arizona ranch, where male guests familiarly nicknamed her “The Rose of the Rancho,” Josephine had covertly carried on an affair with her attorney at the time, Julius McLain Jamison. This latter point was advanced through what newspapers mirthfully dubbed the “honeybun love notes” exchanged between Josephine and Julius (who occupied adjoining rooms at the ranch), which were intercepted by a “negro maid,” Zoe Burney, who forwarded them to Morgan. “Can’t I love my baby,” Julius, then fifty-five years old, cooed pleadingly in one of the notes, much to the amusement of the press. “I just can’t keep away from my pet baby.” Julius urged Josephine to rap on the wall, according to their prearranged signal, to let him know when he could pay her a call.

Despite this evidence, however, Judge Goff, a native Irish Catholic who took a stern view of a husband’s legal responsibilities to his wife, awarded Josephine alimony, albeit a reduced monthly amount of $72 ($2000 today). Morgan may not have met his Waterloo with this particular Josephine, but the affair had certainly constituted a costly lesson for him, both financially and emotionally, about wedding wisely or not at all. Unfortunately, his nephew Clements Smith did not learn from his uncle’s mishap, a failure with fatal consequences for four people. At trial Josephine Clements had claimed that her enraged husband at one point had called her a “goddamn bitch” and threatened to throw her out of a seven-story hotel window. Morgan denied the charge and countered with his own claims of intemperate behavior on his wife’s part, but, whatever the exact truth of the matter, the disputes between the two never came to actual physical violence, let alone multiple murder and suicide.

During the 1940s Clara, whom Clements had made the beneficiary of his will back in 1923, continued to reside at Bluff Hall with her sole surviving son, Clements’ younger brother Singleton Smith, a bookkeeper at the Commercial National Bank, and Charles’s wife Eleanor and their son, Andrew Reid Smith II, although to make ends meet she converted the upper floor of the spacious twenty-room mansion into rental apartments. Occasionally she hosted meetings of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) in her elegant double parlors and dining room, but things were never the same again. After Andrew Reid II in 1946 married Jule Barnes of Prattville, Alabama at Demopolis’ First United Methodist Church, the remaining Smiths resided at Bluff Hall for only another couple of years, when they sold the home and moved to the town of Long Beach, on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, where at the age of eighty-two Clara passed away in 1955. (This was five years after her brother Morgan, who lost a great deal of his copper mining fortune in border raids conducted during the 1910s Mexican Border War, expired on his coconut plantation on the island of Mo’orea in French Polynesia, where he had moved in 1925—finally putting, one presumes, literally thousands of miles of separation between himself and Josephine.) A dozen years after Clara’s demise, Bluff Hall became a house museum maintained by the city of Demopolis, and so it remains today: a beautiful white-pillared southern mansion and popular tourist attraction with an appalling family tragedy buried discretely in its past. Contrarily, the newer house that was raised on South Cedar Avenue, where the Clements Smith family so violently perished, no longer stands. In its place, I believe, stands Demopolis Hardwood Floors.

I toured Bluff Hall some three decades ago, around 1990, without once hearing from anyone the barest whisper of the terrible Smith family murders. By this time perspicacious Police Officer Porter had been deceased for a decade, having retired from the Selma force back in 1963 with an accumulation of more than 35,000 cards in his fingerprint file. His career highlight had come in 1957, when he received a reward of $3800 ($35,000 today) and a personal letter of commendation from FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover for identifying “Reco Glover” as Mississippi native Lemuel Taylor, accused slayer a couple of years earlier of Walter Hart, an off-duty police detective shot in Cincinnati, Ohio while heroically attempting to prevent a holdup at the Grey Eagle Café (Where Good People Meet). Taylor was convicted of Hart’s murder and executed the next year.

Likewise in 1990 the first of Elsie Hildreth Smith’s transitory husbands, George Battles Finch, who had been but a few years older than Elsie, had been dead for several years. Yet some of the key witnesses in that long-ago dreadful affair of November 24-25, 1934, lingered a little longer, including Mems Creagh Webb and his wife, whose daughter Frances “Sister” Webb, just three years old at the time of the murders, in 1983 became one of the first women elected to the Alabama State Senate. Then there was Gertrude Robertson, who, having married later in life, finally passed away in Mobile, Alabama in 1993. Just what had the cook seen and what had she judiciously refrained from telling? At this late date it is unlikely we shall ever know. Even Bert Rosenbush, Jr., who was just a young child at the time of the murders, is no longer with us, having expired three years ago at the age of eighty-nine. Clements’ nephew, Andrew Reid Smith II, who was eight years old at the time of the murders, predeceased Bert Rosenbush by a decade.

While a graduate student during the 1990s (to add a personal note), I wrote my history PhD dissertation on the remarkable northern-born antebellum and Reconstruction-era industrialist Daniel Pratt, founder of the manufacturing town of Prattville, Alabama, located ninety miles to the east. In the course of researching this Crimereads article I discovered, oddly enough, that the woman who introduced me when I last spoke in Prattville two decades ago, was—in addition to being a great-great-granddaughter of Daniel Pratt’s nephew Merrill Pratt—a great-niece, through her Demopolis grandfather Singleton Smith, of none other than Frank Clements Smith, the man who undoubtedly perpetrated, the deferential prevarications of Coroner Hickman and his jury notwithstanding, what likely remains today “the most shocking tragedy that has happened in the city of Demopolis.”

2. Sara Elizabeth Mason’s The House That Hate Built (1944)

Aunt Elizabeth went with her to the back door, and as Linda started toward the garage she heard the key turn in the lock. It was strange, the care and precision with which they all locked their doors now. It was as though they hoped to shut out the evil which came seeping into their house, evil that was tenacious and real, but which, like the fog, could not be shut out. They were only locking themselves inside with their nameless fears.—The House that Hate Built (1944), Sara Elizabeth Mason

Comment: I just read this book from the library. It’s called “The house that hate built.” I heard it was something that happened in Demopolis but she used another town name. It’s a murder mystery and was supposed to have really happened in the 1940s or so. Does anyone know about it?

Reply: Isn’t that a book by Sara Elizabeth Mason? She wrote “Murder Rents a Room,, I think in the 40’s too. If it’s her, I doubt that the story was based on a real event, but the town would almost certainly be based on Demopolis. I haven’t thought about that book in years!—Message board discussion at http://www.demopolislive.com/board/viewtopic.php?f=6&t=5112&start=30, 10 February 2007

Bluff Hall having been an ancestral home of Alabama author Sara Elizabeth Mason’s Glover ancestors (original mansion owner Sara Serena Glover Lyon was a great aunt), it seems likely that Sara, who had been born in Demopolis, though she grew to adulthood in the New South factory town of Gadsden, Alabama, heard an earful about the shocking murders committed in 1934, when she was twenty-three years old and a recent graduate from the University of Alabama, by Frank Clements Smith, the middle son of the couple who had bought Bluff Hall back in 1907 and owned it ever since. Sara drew on her own life experience and family history in her other mysteries (Murder Rents a Room, set in Greene County, ancestral Alabama home of the Glovers; The Crimson Feather, set in Tuscaloosa, home of the University of Alabama; and The Whip, set in Chicago, where Sara attended graduate school); and she evidently did so as well in The House That Hate Built (1944), which is believed to have been set by the author in Demopolis (under another name) and in my view draws loosely on elements of the Smith slayings, particularly in its depiction of bad blood stirred by what are deemed unsuitable matrimonial alliances with previously wedded women.

Nine years ago, when a performance of The House That Hate Built was staged at Demopolis’s annual Tombigbee Haints and Haunts Halloween celebration, the Demopolis Times asserted that “Mason’s book has a kernel of truth to it and is based on a local family feud.” To be sure, any crime novel based to the letter on the Frank Clements Smith murders would have much more resemblance to Alabama-affiliated author Truman Capote’s chilling true crime study In Cold Blood than to any of bestselling Thirties author Mary Roberts Rinehart’s lighter mystery-romances, which Sara Mason’s books, with the exception of her last (The Whip), decidedly favor. One wonders what crime writer Dashiell Hammett’s paramour Lillian Hellman, the author of the biting plays The Children’s Hour (1934) and The Little Foxes (1939) who had maternal Jewish family relations in Demopolis and spent some of her youthful days in the town, might have made of it.

Nine years ago, when a performance of The House That Hate Built was staged at Demopolis’s annual Tombigbee Haints and Haunts Halloween celebration, the Demopolis Times asserted that “Mason’s book has a kernel of truth to it and is based on a local family feud.” To be sure, any crime novel based to the letter on the Frank Clements Smith murders would have much more resemblance to Alabama-affiliated author Truman Capote’s chilling true crime study In Cold Blood than to any of bestselling Thirties author Mary Roberts Rinehart’s lighter mystery-romances, which Sara Mason’s books, with the exception of her last (The Whip), decidedly favor. One wonders what crime writer Dashiell Hammett’s paramour Lillian Hellman, the author of the biting plays The Children’s Hour (1934) and The Little Foxes (1939) who had maternal Jewish family relations in Demopolis and spent some of her youthful days in the town, might have made of it.

Sarah Mason’s The House That Hate Built takes place during a hot and sultry June in the fictional community of Monroe, Alabama, like Demopolis “an in-between place: too large to be a small town and not large enough to be a city.” Despite occasional bursts of boosterism by the local Chamber of Commerce, Monroe’s sole industry is a single cotton mill, most people in Monroe remaining “content for the town to stay as it was” and being “apt to resent any changes.” In real-life Demopolis a cement factory, taking advantage of the limestone deposits in the area, began operation about two miles east of town shortly after the turn of the twentieth century, and it remains in business today, over a century later. There was even a small textiles factory, Demopolis Cotton Mills, though it proved less durable than the cement factory. Notwithstanding the presence of these industries, however, Demopolis remained “distinctly rural,” notes a 2006 article in the Tuscaloosa News. “Cotton was king,” a townsman recalled. “The whole town would be full of wagons with people bringing cotton to the gin.” The town’s biggest employer was John C. Webb & Sons, a family firm of cotton merchants that owned the cotton gin. Mems Creagh Webb, a key witness in the Smith murder case, was one of John C. Webb’s grandsons.

In Demopolis the sprawling, double-porched, Victorian-style John C. Webb house, which comes complete with an ornamental fishpond (and which Clements and Elsie Smith would have driven past several times on the fatal night of November 24, 1934), seems reminiscent of the old Clark mansion in Monroe, as described by Sara Mason. “It had been built in the 1890s by [Linda’s] grandfather in the rococo style of that period,” observes the author with a distinct lack of enthusiasm for the ornate domestic architecture of her parents’ generation. “It was big and inconvenient, with only one bath and no closets. Its bleak lines were angular, and the wide front porch was draped with wooden lace. At odd places were small and completely useless balconies, and a cupola appeared unexpectedly at a second-story corner.”

In The House That Hate Built the old Clark mansion—at present occupied by the spinster Clark sisters, “precise and decisive” Elizabeth and vague and woolly-minded Mary, and their young and attractive niece Linda Clark—is one of three houses on its side of the block on Charles Street, a neighborhood that might most politely be described as genteelly decayed. “Charles Street was old-fashioned and a little shabby, but it was dignified and highly respectable,” explains the author, adding with a faintly ominous note: “Monroe had a saying that the only people who left it were the dead.” Very soon more dead—unnaturally dead this time—will be departing from highly respectable Charles Street.

In The House That Hate Built the old Clark mansion—at present occupied by the spinster Clark sisters, “precise and decisive” Elizabeth and vague and woolly-minded Mary, and their young and attractive niece Linda Clark—is one of three houses on its side of the block on Charles Street, a neighborhood that might most politely be described as genteelly decayed. “Charles Street was old-fashioned and a little shabby, but it was dignified and highly respectable,” explains the author, adding with a faintly ominous note: “Monroe had a saying that the only people who left it were the dead.” Very soon more dead—unnaturally dead this time—will be departing from highly respectable Charles Street.

In between the old Clark mansion and the home of a couple of childless married Clark relations, Will and Suzy Hunter (husband Will, who once had worked for the bank but allowed “good prospects and a fair inheritance” to slip through his fingers, now fecklessly sells real estate and the couple is in straitened circumstances), stands the titular “house that hate built”: the domicile of James Clark, retired bank president and father of Linda by his first marriage, and his second wife, Margaret, formerly Margaret Branch from a prior marriage. Fifteen years ago James’s prim and proper sisters were appalled when their beloved brother wed Margaret Branch after his first wife’s death, a fact of which the new Mrs. Clark was only too well aware. Simmering with resentment against these blue blooded women who dared to look down their noses at her, Margaret persuaded her husband, then “in the first bloom of love,” to build a house for them right next to the Clark mansion, so that the fact of their marriage would be thrown back in the faces of the Clark sisters every single day for the rest of their lives. The tall privet hedge which Elizabeth and Mary planted between the two houses in retaliation has become another source of contention between Mrs. Clark and her sisters-in-law. “So far as I can find out,” reflects one character to Linda, “nobody loved Mrs. Clark, unless it was your father.”

It is not long after the return of another person who seemingly does not love Mrs. Clark, Margo Branch, her recently divorced and drop-dead gorgeous daughter from her prior marriage, that Mrs. Clark is discovered in the music room of the house that hate built, lifelessly seated by the piano. Handsome local doctor Dan Kennedy, called to the scene of the crime, pronounces that Margaret has been fatally and viciously stabbed. In her cold hands the dead woman holds sheet music to “Ase’s Tod” (Ase’s Death), from composer Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite. Symbolic, to be sure, yet never in her life, to local knowledge anyway, did Mrs. Clark actually play the piano. What does the presence of this sheet music signify? Further, just what does the dashing Todd Innis, who four years ago sold an insurance police to the late Mrs. Clark, know about the murder? Or the old yardman Tom, whom Mrs. Clark cruelly evicted from a rental home she owned, leading to the death of Tom’s wife from double pneumonia? And—another moat pressing question in servant-avid Monroe—will Mattie, cook to the Misses Clark, give notice, exasperated beyond endurance with investigators annoyingly buzzing like flies around her kitchen? Sara Mason’s specificity in describing Mattie suggests a character modeled after real-life “help” like Gertrude Robertson:

It is not long after the return of another person who seemingly does not love Mrs. Clark, Margo Branch, her recently divorced and drop-dead gorgeous daughter from her prior marriage, that Mrs. Clark is discovered in the music room of the house that hate built, lifelessly seated by the piano. Handsome local doctor Dan Kennedy, called to the scene of the crime, pronounces that Margaret has been fatally and viciously stabbed. In her cold hands the dead woman holds sheet music to “Ase’s Tod” (Ase’s Death), from composer Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite. Symbolic, to be sure, yet never in her life, to local knowledge anyway, did Mrs. Clark actually play the piano. What does the presence of this sheet music signify? Further, just what does the dashing Todd Innis, who four years ago sold an insurance police to the late Mrs. Clark, know about the murder? Or the old yardman Tom, whom Mrs. Clark cruelly evicted from a rental home she owned, leading to the death of Tom’s wife from double pneumonia? And—another moat pressing question in servant-avid Monroe—will Mattie, cook to the Misses Clark, give notice, exasperated beyond endurance with investigators annoyingly buzzing like flies around her kitchen? Sara Mason’s specificity in describing Mattie suggests a character modeled after real-life “help” like Gertrude Robertson:

Mattie was an individual. When she first came to them Mary had provided uniforms, white aprons, and caps for company, but there had always been some reason why Mattie wasn’t wearing them. Now Mary apologized for her appearance and let it go at that. Mattie didn’t seem to mind the many steps necessary in the old house, and she was always agreeable whether or not she did what she was told to do. She wore a pair of men’s shoes, cut to allow her spreading feet more room, and on her head was an old and greasy felt hat. Otherwise she wore whatever the family gave her.

Before Sheriff Frank Garner finally catches Mrs. Clark’s killer in a startling dénouement, the thread of life of yet another resident of Charles Street is most unpleasantly snipped and Linda Clark’s own continued existence on this erring earth is decidedly put in question. Of the fact that marriage indeed can be murder readers most assuredly will be convinced after a reading of The House That Hate Built. While the novel may not make as grim a read as the real life tragedy of Clements and Elsie Smith, it certainly provides a memorable glimpse of long faded life in a small southern town unpleasantly obliged to confront the murderous paradox of genteel carnage.

Note: All four of Sara Elizabeth Mason’s crime novels have been reprinted by Coachwip as The Sara Elizabeth Mason Mysteries, Volumes I and II.