Thomas Harris could never be considered prolific, publishing just 5 novels in the 44 years since his debut (66% of those novels being Hannibal Lecter-related), but he almost became a household name anyway, when he had the fortune of publishing Red Dragon (his masterpiece) and, more specifically, the bestselling phenomenon The Silence of the Lambs at a pivotal time in pop culture history. The very successful film adaptations of his Lecter novels seem to have permanently overshadowed the source material, however, and even though some might argue that the novels are as noteworthy as they deserve to be, or even slightly overrated, I still maintain this his work is the teeny-tiniest bit underrated (I am holding my index finger and thumb approximately a half inch apart).

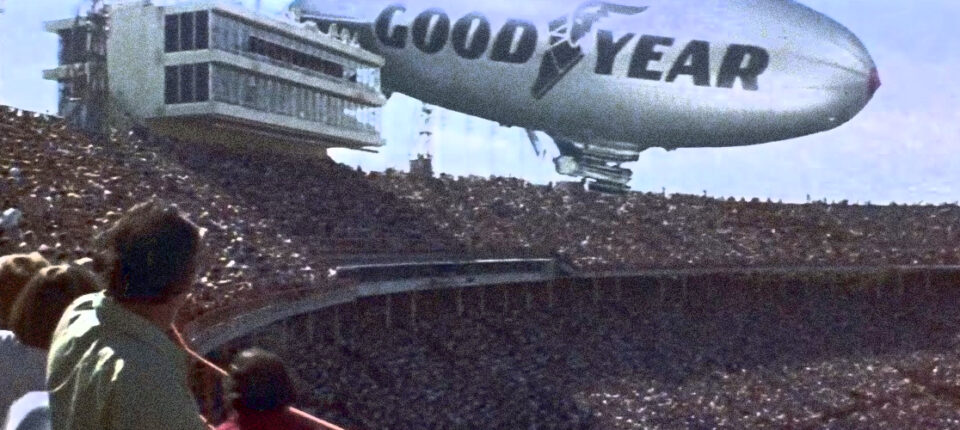

But six years before his big splash with sardonic serial murderer, Harris’ first novel, Black Sunday, published in 1975, was an efficient and fairly popular crime thriller about a very unique way to drop a bomb on a Super Bowl (millions of steel darts? yikes!), and it’s release was just successful enough for him to quit his day job as a crime reporter. But in spite of a high-profile film adaptation containing at least one iconic and alarming scene of the Goodyear Blimp buzzing the 50-yard line during the game, Harris’ real superstar status was still to come, and this book, and the film version, have been mostly forgotten, which is a shame as it was an introduction to many of the writing strengths that would serve him so well later.

In interviews, Harris mentioned how he was inspired by real-time news reportage of the murder of Israeli athletes by terrorists at the Munich Summer Olympics. This extended hostage crisis, which played out live on television for the world, had quite an impact on Harris, and anyone else who saw it, and this book was the result of that shared “text,” published three short years later. In his latest introduction to the novel, the author says his depiction of efficient and driven terrorist ringleader, Dhalia Iyad, was a dress rehearsal for Clarice Starling. And there are more inspirations for Harris’ hugely popular series found in the pages of Black Sunday, such as the haunted but brilliant bombmaker, “Michael Lander,” portrayed suitably tortured by Bruce Dern. Of course, Lander is no Lecter, but a case could be made that this early evil genius was another Harris test-run in a novel front-loaded with an unusual focus on the villain.

A mere 2 years after the publication of this novel saw the release the movie version, directed by The Manchurian Candidate’s John Frankenheimer, which according to reports, received one of the most enthusiastic initial test screenings in Paramount history. However, it famously found itself in a losing battle with another movie that fateful summer, a modest little go-getter named Star Wars. It turned out that world-weary audiences in ’77 wanted a little more escapism and a little less terrorism? Although it’s tough to imagine any movie thriving in the shadow of Lucas’ blockbuster, no matter the subject matter. Just ask Smokey & the Bandit, another bit of escapist entertainment, which also came out that summer and has been relegated to the sale bin of faded memories (I got my copy for .99 cents!).

But despite its hazy place in history (the book and the movie), it’s easy to see what might have enthralled those early test audiences who screened Black Sunday, as well as anybody who took a chance as it withered in theaters. There’s just something undeniably shocking about the main set piece, a daylight attack on a televised football game (see also: The Dark Knight Rises). In the novel, this was an attack at a Super Bowl in New Orleans’ Tulane Stadium, a game between the Washington Redskins (now the Washington Commanders) and the Miami Dolphins. In the movie, this was switched to the Miami Orange Bowl, where the filmmakers received unprecedented access to Superbowl X between the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Dallas Cowboys (Final score: 21 to 17). The NFL allowing the use of real teams, as well as the branding of their championship game, is something you’d never see today. Consider, for example, the massive Oliver Stone football epic, Any Given Sunday, which ended up saddled with team names like the Houston Cattlemen (instead of the Dallas Cowboys?), and the Chicago Rhinos, though the benevolent “Dolphins” did get an upgrade to the Miami Sharks. Fun fact: Stone filmed the fictitious “Sharks” games in the Miami Orange Bowl, just like Black Sunday. The same open-air setting makes for great visuals, and, as the Harris points out, a glaring weakness in protecting a crowd from any sort of airstrike. It should be noted that some of Stone’s reimaginings were a good fit for the conspiracy-minded director, especially the shot of the 50-yard line (the same one the blimp skimmed in Black Sunday) which was no longer sporting the NFL logo in Stone’s film, but instead a pyramid and an eyeball, the sort of iconography that the stoner in Dazed and Confused might have recognized as “the spooky shit you’d find on the back of a dollar bill.”

So the fact that Black Sunday keeps these logos and team names intact is incredibly effective at convincing us that this footage is not just a movie, that the game on our screens is real, and the friendly Goodyear Blimp that infiltrates the airspace of this beloved sport is a betrayal of this revered form of uniquely American televised recreation. Surprisingly, Goodyear also allowed use of its trademark airship to carry the gruesome bomb, under the condition that the explosion of the blimp was shown from the side that didn’t say “Goodyear.” All of this “bleed” between fiction and reality, as well as duplicity between entertainment and history, is what has always fascinated me most about the film version of Harris’ debut thriller. This is also what inspired me to reference such a postmodern invasion of mediums in my new novel, Head Cleaner. In my book, the night manager of “The Last Blockbuster” has a bit of a minor obsession with Black Sunday (among other things). For one thing, it contains possibly the worst helicopter explosion ever immortalized on film (take that, Star Wars: Special Editions!), which makes it very “rewindable.” But also because it contains the extended, real-life football game between the Cowboys and the Steelers, it becomes a prime opportunity for characters in possession of a seemingly supernatural VCR to somehow alter the outcome of an actual historical event, simply by altering the events of a film which used “real” footage.

As the characters begin to realize the implications of what they are doing to the world around them, their impulse to change the ending to suit their tastes, or indulge in their own fantasies, becomes intoxicating. This urge is, apparently, a universal one. Case in point, the notoriously high audience scores reported at the screenings of Black Sunday also came with an addendum; 91% of the screeners who enjoyed the movie said the one thing they found disappointing was that the bomb didn’t go off. This has been interpreted by some as the real reason for its box office failure. Of course, everyone’s rival, Star Wars, never skimps on the final explosion.

I find it comforting, however, and conducive to creativity, when the sometimes troubling impulses of viewers or readers to rewrite films or books to satisfy their worst instincts means they will almost always do this in the most dangerous and cathartic way possible.

***