I like to walk in my neighborhood, preferably in the early morning. And I like to read, preferably literary fiction, but occasionally mystery novels.

When I take a walk in the suburban town where I live, it is not unusual to not run into another human being for an entire block or two, especially if it is a Sunday morning or a long holiday weekend. After having lived my entire adult life in Ohio, this is something I should be used to.

But I’m not. I grew up in a tropical city teeming with millions of people, whose streets were busy and crowed and loud at almost any time of the day. I will never completely make my peace with how suburban Ohio rolls up its carpet at dinner time and doesn’t unroll it until the next day when it’s time to go to work.

When I walk, I’m often thinking about the novel that I’m currently writing, thinking about my characters, mapping out the plot, muttering the dialogue under my breath. This is how I prepare for that day’s work. If I’m in-between novels, I cast about for story ideas for my next book.

Walking is meditative for me. Slowly, over a period of months, an idea forms and grows.

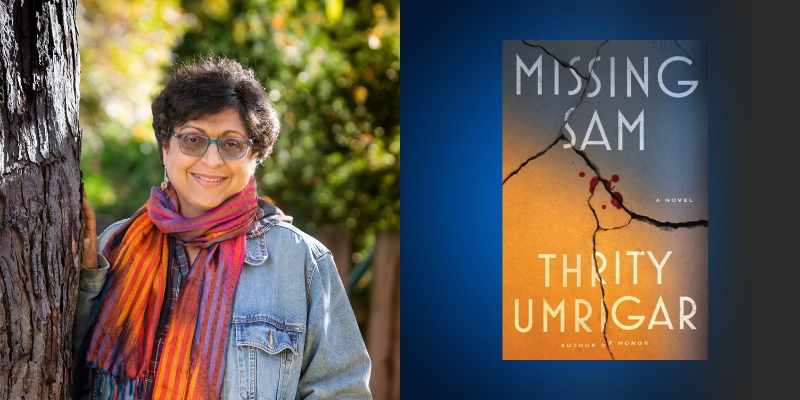

In the case of Missing Sam, the novel started with this casual observation—sometimes, the streets are so deserted that if someone on an early morning walk or run were to disappear, no one would see or hear a thing. They would simply vanish into thin air. Perhaps there was a novel there?

Still, I wasn’t sure. Because the runaway success of Gone Girl had spawned a dozen novels with a plot centering around a disappearance. The books had different settings, of course, but they often featured a white woman who had gone missing and someone else—usually a straight, male partner or husband—who was left behind to deal with the chaos.

I had no interest in retelling that story. But at the time I was conceiving the novel, there was a lot of anti-immigrant sentiment in the air. It was the age of the Muslim ban and Build that Wall.

I asked myself, what if the spouse who remains behind happens to be a gay woman? What if that woman is also brown-skinned? What if she is Muslim and the daughter of immigrants? How would society treat her?

What role would the media, especially social media, play in her treatment? And how would she reconstitute a new identity after realizing that even though she had always felt wholly American, those around her saw her at the Other?

So these two disparate strands–the early morning walks on empty streets, which sometimes looked benign and tranquil and sometimes sinister and menacing, and my growing excitement at the thought of writing a book that was both a thriller and social commentary, a social critique dressed up as a mystery novel—began to come together in what ultimately became Missing Sam.

I was also interested in exploring how our families of origin shape and influence us throughout our lives, how we bring the baggage from our childhoods into our adult relationships. I wanted my characters, Sam and Aliya, a mostly happily married couple, to grapple with how their past has intruded into their present by precipitating the absurd argument that leads to Sam’s disappearance.

As two young, gay women—one, the daughter of an alcoholic Irish-American father, the other the daughter of a loving but traditional Indian-Muslim father—trying to build their careers and their lives together, I wanted them to weigh the price they had paid for choosing each another and decide whether it was worth everything they had sacrificed. I wanted to test the strength of their bonds, not just to one another, but to the parents who had rejected them and finally, to a community and country that treats them with suspicion and hostility.

In this polarizing age, the novel asks: After a traumatic event, is reconciliation and healing still possible? Can we outrun our past without first confronting it? And what are our responsibilities to ourselves, to one another, and to a country that we love but that may not always love us back.

Adrienne Rich famously wrote, “Without tenderness, we are in hell.”

In her bleakest hour, Ali wonders, “if it was all an illusion—American democracy, Sam and me, our marriage.”

Her answer to that question may be the difference between heaven and hell.

***