Twenty years ago, I was leaving (for the second time), and Tina was being born.

Sitting on the backseat of the car, in perfect order inside a transparent file folder, is the dossier that I compiled on her, cutting out newspaper articles, taking notes, photocopying news items. There are also some photographs. I like one of them in particular. It shows her laughing, her hands gripping the handlebars of a motor scooter. I like it precisely for that hearty laugh, her face tilted toward her shoulder instinctively trying to hide from the camera shot, granted nevertheless with an expression of childish mischievousness, of elusive, playful provocation. Tina ’a masculidda. Tina the little tomboy. Loose pants, a striped top on her shapeless, slightly awkward, adolescent body. She must have been fourteen or maybe fifteen years old, and it was her debut, the first time she appeared on the pages of a newspaper. Attempted robbery. But that wasn’t what made her newsworthy, though ultimately young girls who pursue exploits of this kind are rare compared to boys.

Tina was the recognized boss of a band of juvenile boys. That’s what was really worth a photo and an article. A young girl and a band of little gangsters, unaware of the fragility of their age.

Sitting next to the driver’s seat, my cousin Mimmo points his arm out of the window right where I need to turn.

“Here, I said.” He straightens his hair, ruffled by the wind. He wears it long and combed smooth back in an old-fashioned style, so he doesn’t seem either old or young, despite being forty. A look that suits him. Most of all it suits his way of being a doctor, fussy and paternalistic, but with an outward vein of cynical impatience.

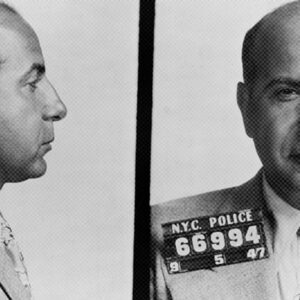

It’s a Sunday in late June, almost six o’clock, but the town is still sleeping or lazily dragging out the day behind the windows, which are closed to keep out the hot, heavy air. I park in a deserted courtyard and head toward the first of two small white and red buildings that mark the border between the Bronx and the Villaggio. Probably the same blurry building that you can make out in the right corner of the photograph: a perfectly squared wall, dark plaster, a piece of asphalt street.

And yet when the photograph was taken, Tina didn’t live here anymore. In truth, she lived here just a short time. It hadn’t even been a year since the entire family—her father, mother, older sister, and brother, who was just a few years younger—had moved from a hovel downtown to the public houses in the Bronx, at the time of the tragedy. Or rather, the incident. That is, when her father died, in that brand new apartment, just inaugurated, the armchair and chairs still covered in stiff, crinkling plastic. He died, shot directly in the face by two shotguns. Three shots exploding from weapons loaded with shrapnel: buckshot mixed with gunpowder and pieces of iron.

***

“That was their door,” Mimmo says. “That’s where the Cannizzaros lived. Tina and her family. Now, I don’t know. Maybe it’s still empty . . . But I doubt it, as we’re starving for homes.”

There are just two doors on the sandstone landing, well-lit by a side window. The door Mimmo had pointed out is right in front of a blank wall where the stairs make a sharp turn. No nameplate, no name written on the doorbell. The other door is open, and a male voice invites us to come in, welcoming us loudly with warm greetings.

The Cannizzaros’ neighbor is a handsome, strong old man, with thick white hair and a lively expression. He’s in his undershirt, sitting in front of a game of solitaire spread out on the table in the combined dining and living room, and doesn’t get up when we come in.

“You’ll have to excuse me, doctor.” Now I notice the bright eyes, steadily fixed on Mimmo, have turned curiously dull; communication has been broken, consensus suspended. His wife has set down the tray with our coffee and taken a seat at a corner on the other side of the table.

“It used to be better than paradise on earth here,” the old man blurts out of the blue. “Better than paradise on earth. Then those people arrived . . . You, sir, know, you know them, sir.”

Which people? My mind jumps to the killer living on the floor above. So I had imagined his ostentatious lack of interest, that absent look on his face. Or maybe the old man still remembers the neighbors he had in the past, the man who was massacred at his front door.

“Sure, I know them. But what are they doing?” My cousin makes light of it. “They aren’t doing anything, nothing bad. And they’re clean and tidy.”

“As for being clean, they’re clean,” his wife confirms.

But the old man shakes his head forcefully. “There’s no pleasure anymore. There’s no pleasure with those people below, on the first floor, that everyone has to pass by.”

“Squatters,” Mimmo finally explains. “The apartment went unrented for too long. So they forced open the door and settled themselves inside. An entire family.”

“There’s no pleasure anymore,” the old man repeats resentfully. “And it was better than paradise on earth. Better, believe me.”

The disgrace gives him no peace. His chest puffs up and his shoulders rise in the effort to launch his protest and keep it high in the air, clearly visible, oozing with passionate hate. The man’s disability, that crutch leaning against the chair, seems harder to bear and more evident amidst the throbbing emotions and repressed energies. The old man is the master of the scene. His feelings invade the home, fill the space, keep it subjugated. Compared to his captive vitality, the two women are only dull, silent extras.

“That’s better . . .” The man sighs, calming down little by little, almost as if Mimmo’s impassivity is rubbing off on him. An impassivity that has nuances of complicity. In this home, Mimmo treats everyone with familiarity, and is treated the same in turn. He’s the family doctor, an important laissez-passer for me too. I know how it is, and I have taken note. After his brief introduction—“my cousin”—no one asked me any questions. It’s not courtesy but simple control of curiosity, a normal exercise in this area between people who are friends, who respect each other. And no one asks about the reason for this visit, which is certainly an unusual one. “I was in the area.” That’s enough, at least for the moment. A convention, a recognized, accepted formality. Form isn’t an empty shell, far from it. It enables you to manage situations. That’s the essential thing.

But now Mimmo gives me a prodding look, encouraging me to come into play. He says, “My cousin, she’s writing a book. Your neighbors, the Cannizzaros, you remember them, don’t you? She’s writing a book about Tina.”

“Tina?”

Sugar has already been put in the coffee, and though I take it unsweetened, at this point there’s no way to not drink it. A small sip and I put the cup back on the saucer.

“Tina?” Hostile, rebuffing: “She was called Cettina.”

***

A name for a little girl, for a sweet little girl, that really didn’t fit her, falling off her on all sides like certain little flounced dresses that her mother resigned herself not to put on her anymore and to replace with pants and a t-shirt.

A name that got in her way like the long hair hanging down on her neck. She just had to go to the barber’s when her father went there, to get rid of that encumbrance. Cettina would see herself in those long mirrors under the neon lights, in the white bib towel that covered her, hanging almost down to her feet, and feel the same as all the other boys. It was beautiful to break free from that hairstyle. Cettina would have liked to make her own name slide away right along with the hair the barber shook out of the cloth at the end of her haircut.

But at eight years old, there wasn’t any way to escape that shrill, clear diminutive. Even if she hid behind her cousins’ clothes, in their old pants, jackets that reached her after unnervingly long peregrinations from one boy to another, from one growth spurt to another. At a certain point someone would call her Cettina and an entire scaffolding swayed unstably at the impact. Her body dislocated and piece by piece was swallowed up by the swamp of an unruly submission.

Spoken on her father’s lips alone that name didn’t jar, ridiculous and sickly sweet, a touchy spot always waiting in ambush in her imaginative soul. “A night wasted when you make a baby girl,” her father would pronounce, repeating the age-old saying, but then he would take her along with him to the café and guide her hand on the billiard stick. Together, they’d roam through the bare countryside and dusty dirt roads, scars of a slightly lighter shade that fur- rowed the pale belly of the plain. He liked to take her along with him, that little girl with tomboyish eyes and a flair for adventure. They were often together on the long rides he had to take for his work as a metal scrap dealer, squeezed tight in the little three-wheeled Ape truck that bounced and squeaked at every gash in the asphalt and dangerously lurched at every stone. He took her alone out, into the world, and not Saveria, with that air of the busy older sister caught up in the most minute domestic duties. And not even Francesco, too babyish, too whiny. In fact, when he saw them arguing, “Let it all out, let it all out,” he’d say, stirring her up. “Hit him now, because when he’s big he’ll be giving you a beating.”

Then all of a sudden, the little Ape truck stood abandoned, and she found herself in a fast car, a new house, wearing her own clothes bought in her exact size, with a father who was brusque, worried, and distant.

Eight years old and she couldn’t get used to her name. Just like Cettina couldn’t get used to the new house. Sure, if they asked her, she claimed she was happy. She boasted about it with a sort of arrogant vainglory. So much so that her cousins, wavering between envy and admiration, commented under their breath, “Haughty girl.”

But Cettina felt she had to show how proud of her father she was. He was a man who knew how to take care of his family and had lifted his children out of that hole of just a few square meters and without any windows, where all six of them had lived and where only their grandmother remained, attached to her way of life, like all old people.

There was no lack of windows in the new house. In fact the light was too strong, too invasive and hot. The muffled sound of footsteps on the sidewalk was far away. She vainly strained to catch the sound of feet shuffling by, which at night, just beyond the doorstep of their old home, used to accompany her sleep. That silence tightened around her chest, provoking a sense of estrangement, malaise. Cettina would open the door and find herself facing a sad hallway, an empty ramp of stairs. The street no longer came directly into the house and the house no longer opened onto the street.

That’s how it has to be, her father said. That’s how it has to be, Cettina repeated to her cousins and friends from her old street, listing the advantages and comforts of their new accommodations. Then she’d list them over again to herself to find some confirmation and deceive her doubts. Because what good was having a telephone, for example (her mother had been the one to have it put in, after long haggling, furious arguments with her father), if afterwards no one could answer when it rang?

“But what did you all get into your heads? To let everyone know about my own business? Do you want to let the whole world know when I’m home and when I’m not here?”

He was a cautious man, and he certainly had good reason to be so. Even if all his caution wasn’t enough to spare him from an unexpected, violent end.

__________________________________