Filmmaker Alan Rudolph has been working in the movie business for most of his life. Coming from a Hollywood family where his dad Oscar was also a director, Rudolph began his career as an assistant director on various projects including the Jim Brown/Gene Hackman flick Riot (1969), eleven episodes of The Brady Bunch and a few films with his mentor, friend (and sometimes producer) Robert Altman. The two worked together on Altman classics The Long Goodbye, California Split (1974) and Nashville (1975). In addition Rudolph co-wrote the Paul Newman feature Buffalo Bill and the Indians (1976). Though Rudolph started directing and writing his own films in 1972, beginning with the hippie horror B-picture Premonition, it wasn’t until the release of his fifth film Choose Me (1984) twelve years later that I discovered his intriguing work and became a fan.

An arty film about various unbalanced Los Angeles people including a recently released mental patient photographer (Keith Carradine as Mickey), a sex obsessed poet (Rae Dawn Chong as Pearl Antoine), a mysterious radio relationship advisor (Geneviève Bujold as Nancy) and the other weary souls who spent hours at the local loser’s lounge called Eve’s, a jazz bar owned by a former hooker (Lesley Ann Warren) with the same name.

While Choose Me was a small film that didn’t have a large advertising or marketing budget, it did have the soulful theme song “You’re My Choice Tonight (Choose Me)” crooned by 1970s soul sex symbol Teddy Pendergrass. Written and produced by Luther Vandross and Marcus Miller, the song served as a comeback for Pendergrass after a horrific 1982 car accident that left him a paraplegic.

Pendergrass’ manager Shep Gordon asked Rudolph to direct the music video; though he turned down the offer, Rudolph claimed he could make a feature for the same budget. The filmmaker has said that his script was inspired by repeated listening to Vandross’ demo of the moody romantic track. The Pendergrass single was a favorite of New York disc jockey Frankie Crocker and his frequent spinning of “You’re My Choice Tonight (Choose Me)” encouraged me to check out the movie.

Playing on the east side of Manhattan at the Coronet Theatre, not far from where my messenger job was located, I went solo one night. From the moment neon soaked Adam Street was seen on screen in the opening credits that featured suited pimps, ladies of the night and beautiful Eve slow dancing in the street, I knew that Alan Rudolph, with his dreamy atmosphere and spellbinding style, wasn’t just another Hollywood director hoping to make blockbusters.

In that 1980s era of big budget flicks such as Back to the Future and Rambo, here was something different. Upon further viewing it became apparent that Alan Rudolph was more interested in stories and characters talking rather than high concepts and explosions. Choose Me was a mixture of genres ranging from musicals (that opening was pure Gene Kelly inspired), love stories, Euro gangster tales and barfly narratives.

Coming at a time when I was discovering classic noir writers David Goodis and Cornell Woolrich, this picture fit in well their romantic losers and night people. In their own way, all of the characters were tough, but in desperate need of happiness and someone to love. Though they were all somewhat sad, “the blues” was not only one of the film’s themes, it was also heard in the music played during a few scenes at Eve’s. At one point we hear a recording of the blues/jazz classic “Trouble in Mind” played by jazz saxophonist Archie Shepp and pianist Horace Parlan.

The title track from an album the duo recorded and released in 1980, it was that version of the song that inspired Alan Rudolph’s next picture. At a 2023 American Cinematheque panel discussion with screenwriter Larry Karaszewski and Choose Me producers Carolyn Pfeiffer and David Blocker, Alan Rudolph stated, “I said when I heard it that I’m going to write a movie someday called “Trouble in Mind,” because it’s such a great title.”

Georgia White recorded the song first in 1924, but since then “Trouble in Mind” has been covered by many artists including Sam Cooke, Dinah Washington, Nina Simone and Johnny Cash. For the film Rudolph (or perhaps soundtrack composer Mark Isham) recruited British singer Marianne Faithfull, her voice laced with doom. Used as the opening theme song Faithfull’s vocals, beautifully beat down from years of drugs and cigarettes, captured the mood perfectly. Isham’s trumpet playing on the track exquisitely captured the romantic melancholy and criminal minded vibe of the aptly named Rain City.

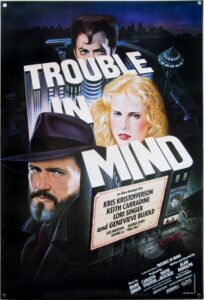

As Faithfull sorrowfully sang we were introduced to the main characters that included newly released prisoner (and ex-cop) John Hawkins (played with brooding resentment and passion by Kris Kristofferson), his old friend Wanda (Geneviève Bujold) who owns a diner and tenement in the slums of Rain City and uprooted trailer park couple Coop (Keith Carradine) and Georgia (Lori Singer), who would soon come to town with their infant Spike looking for a better life.

It was the beautiful, but naive Georgia and her urbane longings to “live in the city” that set off the plot that opened quietly, but closed with a bang. Rudolph once again blended genres, and made Trouble in Mind half throwback noir from the Bogie school with the other side being a dystopian science fiction complete with a militia in the streets and signs of a forthcoming battle brewing (“Ready for War” posters hung on buildings as the army violently clashed with peaceful protestors) in the background. There was also a touch of Godard’s bugged out Alphaville (1965) and the post-punk Liquid Sky (1982) as seen in the new wave influence in the clothes and hairstyles of a few of the characters.

While Trouble in Mind has been called surreal, the story was actually rather straight forward though the landscape was very strange. There was a retro futurism vibe to the film that, when I first saw it, reminded me of Blade Runner (1982) as well as Walter Hill’s rock musical Streets of Fire (1984). In Alan Rudolph: Romance and a Crazed World by Richard Ness, the author noted, “Producer Carolyn Pfeiffer described it as existing somewhere between Bogie and Bowie.”

Though Trouble in Mind was made on the cheap in Seattle, the exterior locations had an otherworldly appeal, a depressing metropolis at the edge of time. “The city is the promise of something better,” Georgia read from a magazine in the beginning of the film. Coop smirked. “I’ve been to plenty of cities and they ain’t nothing but trouble,” he warned.

Later that day, after Coop stole cash from the safe construction company, he rushed home and quickly boogied his small family to Rain City. Though he left their nameless burg looking like a hick, shortly after arriving to the big town he had a stylistic transformation. As luck (good for some, bad for others) would have it, Coop parked their camper in the alleyway next to Wanda’s cafe where destiny awaited them both. The couple entered the diner as though it was a spider’s web and soon they’d be devoured.

For Coop it’s the cool criminal and poet Solo played by Joe Morton, for Georgia it’s Wanda and Hawk, who both fall in love with her. It doesn’t take long for Coop to be seduced by the city and the prospect of making a few dirty dollars, none of which he brings home. Instead he spent the cash on hookers, drugs, ugly clothes and bad haircuts. Meanwhile, Georgia was held captive in the camper making paper dolls awaiting his return. Keith Carradine played the part of the wannabe tough guy perfectly, a dude who loved his woman but was easily swayed.

In the center of the chaos was Hawk, another torn character who tried to be a gentle giant in a trench coat and fedora, but who often showed a more brutal side when it came to sex. He forced himself on Wanda after she gave him an apartment. The next morning, acting as though he did nothing wrong, Hawk was surprised when Wanda punched him in the face and loosened a few teeth. Afterwards she befriended Georgia, invited her to take a bath in her apartment and gave her a waitress job at the diner.

In Trouble in Mind, sexuality was not narrowly defined. In one scene annoying jerky boy gangster Rambo (a funny as hell Dirk Blocker) asked Hawk if Wanda was a lesbian. The bearded ex-con blurted, “Is that what you came here to ask me?” Rambo’s kingpin boss was Hilly Blue, the pseudo classy gangster played with relish by Divine, best known for his roles in John Water’s films Pink Flamingos (1972) and Polyester (1981). Blue was the first film character Divine played wearing men’s clothes.

Hilly Blue was running things on the crime side of Rain City and ruled without any mercy. As an insight to his damaged psyche he snipped, “My mother didn’t love me one bit. She never showed me any affection. She never even kissed me…once; had to put her out of her misery. Women are despicable…especially mothers.”

I must give Alan Rudolph props to more than a few of his casting choices including comic George Kirby as the irate police chief who pulled Hawk out of jams while offering sage advice and John Considine as whiny gangster Nate Nathanson, who Coop and Solo robbed and set off a violent chain of events.

Trouble in Mind was also a movie about relationships (beginnings and endings) in various degrees. “You push me, but you don’t like where I go,” Coop told Georgia, though the words could’ve applied to any of the characters. While Coop ran the streets with Solo, his rival Hawk was making moves on Georgia, taking her out to an expensive restaurant and rapping hard in that grizzled Kristofferson voice. From there the film criss crossed in various directions and climaxed with a wild shoot-out at Hilly’s massive mansion that should’ve made Peckinpah proud.

Although there were some positive notices about the Trouble in Mind when it was released, no critic was more pleased than Roger Ebert, who awarded the film four stars in the Chicago-Sun Times. “To really get inside the spirit of ‘Trouble in Mind,’ it would probably help to see ‘Choose Me’ (1984) first. Both films are the work of Alan Rudolph, who is creating a visual world as distinctive as Fellini’s and as cheerful as Edward Hopper’s. He does an interesting thing. He combines his stylistic excesses with a lot of emotional sincerity, so that we believe these characters are really serious about their hopes and dreams, even if they do seem to inhabit a world of imagination.”

While I can see the influence of both Choose Me and Trouble in Mind in the work of Wong Kar-wai and Steven Soderbergh, director Alan Rudolph has never gotten the accolades or awards that some of his contemporaries have received, but that never stopped him from further delivering wonderful films including The Moderns and Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle. Recently I watched his brilliant stalker thriller Remember My Name (1978) for the first time, and was impressed all over again.

___________________________________

Many of Alan Rudolph’s films, including Remember My Name and Trouble in Mind, can be seen on Tubi.