Give me an 85,000-word novel to write, and I’ll dig in eagerly, but tell me to write a 2,000 to 3,000-word synopsis of the same novel and I might sulk a little. Admittedly, brevity has never been my strong point.

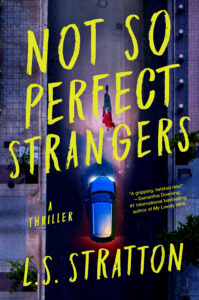

So, needless to say, I struggled when I had to come up with one line to describe my thriller, Not So Perfect Strangers, inspired by the Alfred Hitchcock film Strangers on a Train, which was based on the 1950 novel of the same name by Patricia Highsmith. I needed something pithy that conveyed not only the premise but also encapsulated everything I’d been trying to say in this book thematically. After a few drafts, I finally settled on, “A twisty thriller inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, shown through the lens of racial dynamics and feminism.”

I was quite proud of myself until my agent mentioned that when she was talking about my book at her staff meeting, she said, “Not So Perfect Strangers is the white savior trope turned on its head.”

My first thought was, “She is so much better at this than I am!” My second thought: “And this is why she’s my agent.”

Because it’s true; this novel is the white savior trope turned on its head, showing what happens when a seemingly well-intentioned (though unstable) woman with a white savior complex takes things to deadly proportions, unleashing a domino effect that even she couldn’t see coming.

From Atticus to Skeeter: A Long History of White Saviors

To explain how Not So Perfect Strangers plays with the white savior trope, I first have to try to explain what exactly the white savior trope is. Luckily, there are plenty of examples in literature and film to reference. For example, in To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus Finch, a white lawyer defends a Black man, Tom Robinson, against rape allegations to the consternation of the white community in his small Alabama town. In The Help, Skeeter Phelan, a white socialite, empowers Black maids Aibileen, Minny, and their friends by using their accounts as servants to write a tell-all book. The list of “white saviors” in film and TV is even longer: Gabe Kotter in Welcome Back, Kotter, Louanne Johnson in Dangerous Minds, Nathan Algren in The Last Samurai, Erin Gruwell in Freedom Writers, Leigh Anne Touhy in Blind Side, Dan Dunne in Half Nelson, Tony Lip in The Green Book, Eileen Fitzgerald in Alaska Daily and on and on and on.

In each case, the white saviors are willing to stand up to the powers that be to help a racial/ethnic and often impoverished person or community to gain justice or self-actualization. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with what the white savior is doing; actually, at face value, it’s very laudable. The message of their stories is meant to be positive and uplifting. For many readers and audiences, it can make for a “feel good” book or movie, which would explain why this trope persists.

However, there are big issues with the “white savior” character. Not only does it promote the idea that the only way racial/ethnic minorities can achieve justice or empowerment is with the help of a white person, it unwittingly promotes another form of white supremacy.

The white savior takes the lead, stepping in front of or outright ignoring the organizers and leaders in the communities that are trying to bring about the same change they wish to accomplish. In fact, in the white savior narrative, these local organizers and leaders may not exist at all. The white savior character is elevated in the narrative so that they become the focus of the story, and most of the story is told through their lens. Their struggles, misgivings, day-to-day life and good deeds take center stage while the “victims” they are trying to help or save fall to the background. For example, though Tom Robinson is the one on trial and his Black community is the one facing Jim Crow racism, it’s Atticus Finch, his family, and their perspectives of events which account for most of To Kill A Mockingbird.

Giving the “Victim” a Voice and Agency

In Not So Perfect Strangers, Madison Gingell, a Washington, DC, socialite, truly wants to help Tasha Jenkins, a domestic violence victim, whom she meets by chance one evening. She feels a connection to Tasha. She’s also a victim and survivor of abuse and has a husband whom she wouldn’t mind getting rid of. So, Madison makes a similar offer to Tasha that Bruno Antony made to Guy Haines in Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, but unlike Bruno, she doesn’t believe she’s motivated by just anger and retribution, but by a higher purpose.

She believes she’s done the work of a good ally, attending the diversity and inclusion workshops. She calls her friend on her racism and “Karen”-like behavior. She’s married into wealth but is bemused by the self-entitled behavior of those in her social circle. Madison would probably describe herself as a feminist as well.

“I’m a big believer that women should help each other, Tasha,” Madison says before telling her about her “criss-cross” murder plan. “Don’t you think?”

Madison’s goal isn’t just to save Tasha from her abusive husband and rid herself of her own spouse, but also to help Tasha realize the powerful woman she believes Tasha has the potential to be. And Madison will do what she has to do in order to accomplish her goal—even if Tasha doesn’t want her to do it, because Madison believes she knows what’s best.

Madison has all the hallmarks of the white savior character—just in a diabolical package.

I could have told the novel entirely from Madison’s perspective and made her the star (she gave me a lot to work with as a character), but I felt it was important to diverge from the white savior narrative in that regard. I wanted the reader to ask, “What does Tasha feel about her situation and Madison’s offer? Does she see herself as a victim who needs to be saved? What does she think of Madison’s true intentions? How does Tasha respond to all of the twists and turns that happen after Madison has her way?” Those answers had to come from Tasha, and could not be given from Madison’s perspective.

I refused to let Tasha fall to the background while Madison took the lead. Because her voice and her story matters just as much as Madison’s. Because it makes for much more dynamic storytelling and gives a twist to a problematic, antiquated, and frankly, tired trope.

***