Although it’s long been said that Sherlock Holmes, Mickey Mouse and Superman are the most familiar characters in fiction – especially if we take into account all the variants of those characters – you could make the argument that the Universal monsters, the creatures first adapted from vintage tales and legends by Universal Studios from the 1920s onward, are equally recognizable. Their faces appear on Halloween candy, they stomp and snarl through cartoons and pop music and commercials and their on-screen iterations are endless, timeless and modern, as the recent “Frankenstein” adaptation demonstrates.

These creatures inspire nightmares and box-office and, after more than a century of film, continue to be a cultural force.

Inspired in part by the relatively recent films that bring these legends to life, I wanted to touch on the waves of film adaptations of what might be Hollywood’s first and most durable intellectual property. (Sorry for bringing it down to the IP level, but the box-office immortality of the creature creations is a big factor in their cultural immortality.)

A quick note: I’m limiting myself to only a handful of what I’m defining as the Universal monster “stars,” namely Dracula, Frankenstein (and his monster), the Wolf Man, the Mummy, the Invisible Man and the Creature from the Black Lagoon. You could argue that other Universal staples like the Hunchback of Notre Dame and the Phantom of the Opera would be appropriate additions to the list and I wouldn’t even disagree. But I had to narrow the field a little. (And those monsters still get a shout-out.)

I’ll note that also in the spirit of narrowing the field, I’m not talking a lot about TV and book adaptations, although there will be some note of the oddest of those works.

One thing to keep in mind throughout is that a major factor in every successful film adaptation of these classic creatures is sympathy. Monsters can be monsters even if we don’t sympathize with them, but it is our sympathy that makes them so terrifying, especially in how it recognizes the feeling of, “There but for the grace of god go I.” Who hasn’t felt like Frankenstein’s creature, alone and scorned, relieved to experience any kindness, like a cigar offered by a new friend? And any of us can sympathize with the idea of our bodies being out of our control and our thirsts and hungers being too much for us to stand.

The formative years

The Universal monster films began with a silent short, “Dr. Jekyll and Mister Hyde,” released in 1913 and based on Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novella “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” but what’s considered the bedrock of Universal’s monster films came with a one-two punch in 1923 and 1925 with epic silent versions of “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” and “The Phantom of the Opera,” both starring Lon Chaney. Author Ray Bradbury recalled the impact seeing a Chaney film had on him as a youngster and said that Chaney “acted out our psyches.” Universal founder Carl Laemmle wanted Chaney to star in the studio’s adaptation of “Dracula” but Chaney was under contract to MGM. By the time “Dracula” was being made by Universal, Chaney had died: the master of character makeup and so-called “Man of a Thousand Faces” died in August 1930 from complications of bronchial cancer, according to The New York Times.

Bela Lugosi was ultimately cast as Dracula for the film, which adapted the stage play by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston that itself was adapted from Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel. It’s likely it is the stagey quality of the film and Lugosi’s theater-friendly performance – he’d played the role on stage – that leaves some who see it today put off by the classic film, but those same elements lent the film its otherworldly impact when it was released around Valentine’s Day in 1931. (If you get the opportunity, by all means watch the 1931 Spanish-language version of the film, which features an entirely different cast, led by Carlos Villarias as Dracula and Lupita Tovar as Eva, the Spanish-language version of Mina. Villarias is over-the-top in his performance at times, but director George Melford’s film – legendarily shot on the same sets as the English-language classic directed by Tod Browning, after hours – has very different scenes and is considered by some to be superior to the Lugosi version. I’m not sure that’s the case, but it’s worth seeing.)

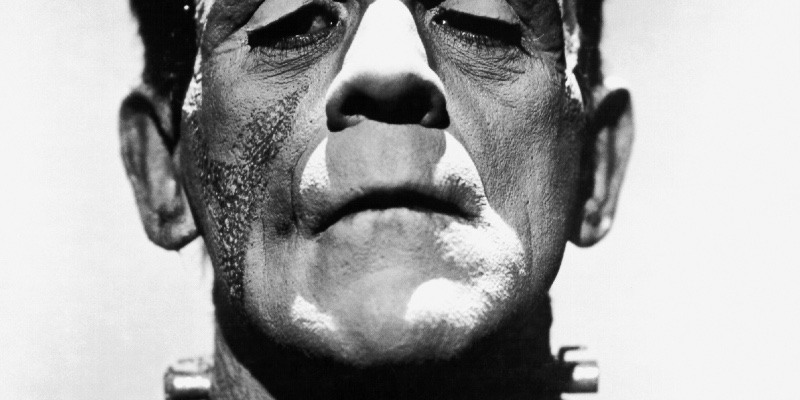

“Dracula” has the most theatrical quality of the early Universal films and while it’s fascinating and beautiful, the monster films that followed were more cinematically dynamic and were pure Hollywood. “Frankenstein” in 1931 and the sequels “The Bride of Frankenstein” and “Son of Frankenstein” drew visual inspiration from expressionistic German films like “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” and prompted generations of horror film watchers to consider elevated lab tables and harnessed lightning as the only way to make a monster. It’s the method that is present in films and our collective consciousness despite author Mary Shelley’s less-specific creation details in her 1818 book.

The 1930s were dotted with the OG Universal monster films and those movies are still regarded as the best of the genre despite the passage of nearly a century. “The Mummy” was a restrained tale of ancient curses before it transformed, delightfully so, into a wild series of creeping terror sequels. “The Invisible Man” was an exploration of madness that prompted effects-driven sequels that turned into tales of derring-do. “Werewolf of London” in 1935 set the template for man-into-beast transformation stories. “Dracula’s Daughter” explored the distaff side of terror and hinted at desires mainstream Hollywood didn’t often acknowledge.

It was the Universal monster films of the 1940s that, for some, ruined the atmospheric tone of the original films. For me, the films of the war years and period to follow are overall my favorites.

It was a double-feature rerelease of two of the 1930s classics that convinced Universal it had money-generating characters in its hands into the 1940s and decades beyond.

The revival

It’s not as if the earliest Universal monster films had not been successes. According to IMDb, director James Whale’s original, Karloff-starring film was the biggest hit of 1931, topping even Charlie Chaplin’s “City Lights.” Browning’s 1931 “Dracula” was the sixth-highest grossing film of the year. Sequels and other Universal releases did well throughout the 1930s.

But it was August 1938 showings of “Frankenstein” and “Dracula” – as well as “Son of Kong” – at the Regina-Wiltshire Theater in Los Angeles that convinced the studio that the films could be ongoing, even eternal money machines. The reception to the re-released monster films was so great and demand for tickets was so pervasive that the theater scheduled showings for 21 hours every day.

Lugosi, who hadn’t had a starring role since 1936, found himself in great demand again. He starred in five films released in 1939, from the quickly devised-and-produced “Son of Frankenstein” to “Ninotchka,” starring Greta Garbo. It all came not a moment too soon for Lugosi, whose home was foreclosed on during his couple of years without meaningful work, according to the Bela Lugosi blog. The theater hired Lugosi to make nightly appearances at screenings. Boris Karloff, who had rarely not been in demand, played the monster for the final time in “Son of Frankenstein” in 1939 and appeared in seven films that year, including “Tower of London.”

After the success of the double-feature, Universal quickly struck hundreds of prints of “Dracula” and “Frankenstein” and put them into wide re-release.

Karloff and Lugosi found themselves in the vanguard of a new series of horror films in the 1940s. They didn’t always star in the films, but they enjoyed meaty roles in what came to be called Universal’s “monster rally” films. And more creatures than just Frankenstein and Dracula and more actors than Karloff and Lugosi attended the 1940s rally.

“The Invisible Man Returns,” starring Vincent Price, was released in 1940, following up on the 1933 original. “The Mummy’s Hand,” starring actor Tom Tyler and reused footage from the 1932 original, came later in 1940. Beginning in 1941, Universal monsters followed in quick succession: “The Wolf Man” in 1941 is one of the best and typifies what I meant earlier about a sympathetic monster. Lon Chaney Jr., actor son of the classic “Phantom,” played for the first of several times the tortured Larry Talbot. The younger Chaney, whose given name was Creighton, was groomed by Universal to take up the legacy of his father. He led one of the best casts of any horror film: Claude Rains, Ralph Bellamy, Maria Ouspenskaya and Lugosi in a small role as a werewolf who gets the story rolling.

In quick order beginning in 1942, Universal released “The Ghost of Frankenstein,” “Invisible Agent,” “The Mummy’s Tomb,” “Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man,” a “Phantom” remake, “Son of Dracula” featuring Chaney Jr., “The Invisible Man’s Revenge,” “The Mummy’s Ghost,” “House of Frankenstein,” “The Mummy’s Curse,” “House of Dracula” and in 1948, a film seen by some as a betrayal of the monsters’ integrity: “Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.” The monsters – Frankenstein, Dracula, the Wolf Man and the Invisible Man – are set against the titular comedy team, who would subsequently take on other monsters in their own series.

I love “A and C” and feel it doesn’t permanently injure the monsters’ reputations. And how can we turn up our noses at only the second time Lugosi played Dracula in the movies?

A bigger betrayal could be found in the “House” movies, that promised so much – really, who didn’t want to see Dracula and the Wolf Man and Frankenstein’s creation battling? Unfortunately, we didn’t get enough of that. John Carradine, who had a small role as a woodsman in “Bride of Frankenstein,” played Dracula in “House of Frankenstein” (for the first time, as we’ll note much later) but is killed off before the story barely gets started.

One of the smartest things Universal did with this second wave of monster films was to set them in the United States. With “Son of Dracula,” (1943, starring Lon Chaney Jr.) the vampire migrates to the American south and there’s a delightful southern gothic vibe to the film, with hanging moss, swamps and an estate called Dark Oaks. And partway into the “Mummy” series, the Mummy (also Chaney by this point) is in the small town of Mapleton, Massachusetts. The American relocation brought a lot to the atmosphere of the pictures.

Those 1940s “monster rallies” were the golden age of the Universal horror films, as the 1950s would soon make evident. In the 1950s, the Universal monster properties discovered teenagers and blood – lots of full-color blood, but only after a final Universal monster was born.

Creatures vintage and ‘modern’

There was a “last gasp” of sorts for the classic Universal monsters and it took the form of the debut of a new creature. In 1954, “Creature from the Black Lagoon” established a new type of monster – aquatic and not a cursed or undead human, but a prehistoric beast – in a new type of setting, the Amazon (and South Florida in the two sequels) and it followed the pattern of asking moviegoers to sympathize with a creature that only wants to be left alone but is kidnapped, hounded and endangered by the hand of man. The Gill-Man suit is among the most accomplished horror designs – by Millicent Patrick – and costumes in movie history. The first two of the three films were made in 3-D and were quite successful. But filmmakers as varied as John Carpenter, John Landis and Ivan Reitman proposed long-after-the-fact remakes but they never happened. Not until director Guillermo del Toro, after having failed to interest Universal in a remake in the early 2000s, did a Creature of sorts re-emerge in a new treatment by del Toro. More on that later.

After the Creature films, the Universal monsters’ legacy was upheld elsewhere.

Hammer Film Productions was founded in 1934 but the British movie studio didn’t have worldwide impact until its first color horror film, “The Curse of Frankenstein,” in 1957. “Dracula” – known in the United States and some countries as “The Horror of Dracula” – followed in 1958. The films and those that followed, like “The Mummy” in 1959, were a seismic event for filmgoers thanks to several elements: Stars like Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing as well as a stable of dependable British actors; period settings; stories enlivened by spicy plot points; and graphic gore and violence, all lovingly portrayed in color.

American moviegoers in particular were accustomed to the black-and-white Universal horror films that had continued from the Prohibition era to the Eisenhower presidency. The Universal films seemed tame by comparison to Hammer, which continued to release films in those three main series until the mid-1970s. It was a slate of films and timeline that rivaled those of Universal.

Through it all strode Cushing and Lee, commanding actors with physical presence, by all accounts gentlemen and gentle men who seemed to relish – with good-natured irony – stardom in the world of horror films. Seven Frankenstein films were released, anchored by Cushing, through 1974’s “Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell.” Nine Dracula films were released, often co-starring Lee and Cushing, through their final collaboration, “The Satanic Rites of Dracula” in 1973. Four Mummy films were made from 1964 to 1971 and certainly the best was the first, with Lee as the unstoppable eternal menace.

Other Hammer films were strikingly cast and shot, including “The Curse of the Werewolf,” starring Oliver Reed, and “The Devil Rides Out,” with Lee on the side of the angels. And Hammer knew it could feature beautiful actresses in skimpy outfits, like Ingrid Pitt in “Countess Dracula” in 1971, and attract moviegoers.

Hammer, seen as subversive by some at the time for its gore and spiciness, brought a physicality with its handsome, active leads and, in the latter Dracula films, modern-day settings.

Hammer was the best the genre had to offer for Universal-style monsters for much of two decades, the 1960s and 1970s. Some of the other products that moviegoers saw were … of lesser quality, shall we say? You don’t have to take my word for it. You can probably find two lesser but still enjoyable films – “I Was a Teenage Werewolf” and “I Was a Teenage Frankenstein,” both released in 1957 – somewhere. Don’t feel like you have to look up two even lesser but inept thrillers, “Billy the Kid Versus Dracula” and “Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter,” both released in 1966 and directed by William Beaudine. John Caradine returned as the undead count in the former.

If those low-budget movies didn’t do it for you, you could always turn to comic books in the 1960s. I’m not talking about Superman or Spider-Man. I’m talking about “Dracula,” released by Dell Comics in 1966 and 1967, or its companion titles, “Frankenstein” and “Werewolf.” These were not the spooky and atmospheric comics released by Marvel and DC within just a few years. No, in these instances, the monsters were superheroes. They’re worth looking up for their audacity.

Maybe it’s more fruitful to enjoy some of the many international Dracula, Frankenstein and Mummy movies that popped up in drive-in theaters for decades. They exude low-budget creativity and oddness.

Speaking of low-budget oddness …

Monsters get groovy, baby

The 1970s were a damn weird time for the Universal monsters and their unauthorized remakes and reboots. I guess I could have just ended that sentence after “The 1970s were a damn weird time.”

The 1970s were the decade that saw not only oddball paperback horror novels like the Frankenstein Horror Series in 1972 and 1973 – nine novels that showcased Frankenstein’s creature and other horrors – but the winding down of Hammer’s horror series and more exploitation films that built on, and happily surpassed, those 1960s horror westerns. Plus, by the end of the decade, the release of a big-studio Dracula film that felt like the birth of the Big Hair Vampire.

It’s appropriate that the 1970s classic monsters films began with a film that strove mightily for classic status but failed miserably. Anyone reading Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine early in that decade was aware of a film on the horizon, “Dracula vs. Frankenstein.” The film, directed by low-budget and exploitation director Al Adamson, was touted by Famous Monsters editor Forrest Ackerman because the cast included former horror film mainstays Lon Chaney Jr. and J. Carrol Naish. (Ackerman had a brief role also.) But the film is awful despite, ironically enough, paying off more on the promise of teaming monsters than some of the 1940s Universal films were able to do.

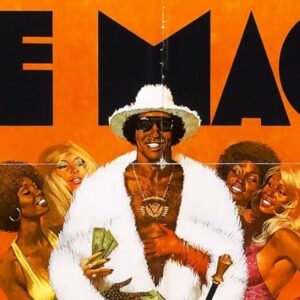

The decade of drive-in-movie-level horror and the final Hammer horror films was honestly dominated by some films that road the crest of a wave of films that were sometimes-demeaningly labeled “Blacksploitation” or “Blaxploitation” films. “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song,” directed by Melvin Van Peebles, is regarded as the first and is a crime film. But Black-starring horror films were quick to follow.

The first was “Blacula,” released in 1972 and starring William Marshall as Prince Mamuwald, who in 1780 goes to Transylvania to seek Dracula’s help in ending the slave trade. Dracula turns him into a vampire and locks him in a coffin for two centuries. When Mamuwald is out, he joins modern society as an urbane predator. The success of “Blacula” guaranteed other Black horror films, notably “Blackenstein” in 1973.

Easily the best of the wave of Black horror films is “Scream Blacula Scream,” released in 1973 and again starring Marshall as Mamuwald. Marshall is majestic and he leads an incredible cast that includes Don Mitchell, Pam Grier, Lynn Moody, Bernie Hamilton, Craig Nelson and Michael Conrad. The sequel is better than the original and is the model of what a classic monster story set in modern day should be.

The 1970s films drawn from Universal monsters were oddly satisfying, even thought it was sad to see the Hammer reign end. Hammer’s final Dracula movie, “The Satanic Rites of Dracula,” capitalized on the modern-day setting earlier adopted in the series. Cushing played a Van Helsing descendant and Joanna Lumley played his granddaughter. Lee, as usual, makes the biggest impression in the film, playing Dracula as a Howard Hughes-type millionaire recluse who wants to preside over the end of the world. And then the Hammer era was over.

The 1970s closed with one of the strangest yet most successful Universal monster films, director John Badham’s version of “Dracula,” starring Frank Langella, who had played the character on stage in a revival of the vintage 1924 play by Deane and Balderston. Badham makes some choices here, chief among them focusing on the romantic relationship between Dracula and Lucy. (As usual, Hollywood played fast and loose with Stoker’s characters, eliminating most of the male cast and switching the Lucy and Mina roles) The 1979 film has some very dated elements, including Langella’s big hair, Laurence Oliver’s accent as vampire expert Van Helsing and some laser-lit, smoky scenes, particularly a red-hued romantic clinch that could have been shot at Studio 54.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention director Mel Brooks’ classic 1974 film “Young Frankenstein” which, like “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” in 1975, solidified some of the tropes of classic film genres for a new generation – example: the police officer with the wooden arm – and very nearly ruined them for some of us. I can’t see an Arthurian epic without thinking of “Holy Grail” and I can’t see a black-and-white creature feature without thinking, “Eye-gore.”

The 1980s, with Freddy and Jason and lesser-remembered killers, seemed to mostly ignore the classic Universal monsters. Slashers were the order of the day.

It wasn’t until “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” in 1992, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, that a classic creature made a comeback. There’s a lot to like about Coppola’s movie and the cast feels like a who’s who of Hollywood at the time. But as a fanatical fan of Stoker’s novel, I felt like the movie’s title was itself a lie. I was disappointed that yet another film, particularly one so important and high-profile, had strayed so far from the source material. I was impressed that it was one of the Dracula films that included Quincey Morris (played by Billy Campbell), the Texan whose Bowie knife skills spell doom for Dracula in the novel.

A few years later came director Stephen Sommers’ 1999 “The Mummy” and who would have thought the corniest of the Universal monsters – “Look out, the Mummy is headed toward us!” “No problem, it’ll take him an hour to limp over here.” – would be such a hit? But the combination of the exciting plot, incredibly charismatic cast (Brendan Fraser, Rachel Weisz and Oded Fehr among many) made this movie and a series of sequels and spinoffs irresistible.

A rebirth of the Universal monster universe was so close …

For a moment there, in the mid-2010s, we almost had a renewal of the Universal horror genre. Then we saw the movies. Sorry if that sounds like a Rodney Dangerfield line, but the underperformance of the Dark Universe films – even before they were officially known as that – doomed the effort.

When Universal saw the success of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, some executive undoubtedly said, “Hey, we have decades of well-known, well-loved characters and storylines just waiting for a box-office-friendly refresh!”

It seemed like a good idea, but the films that led the effort were either not good or not conducive to bundling into an Avengers-style universe. Honestly, “Van Helsing” had earlier cast doubts on the whole enterprise in 2004. Released by Universal (unlike some of the later films, which were not made as part of a cohesive effort) it was as if the Marvel movies had jumped right into an Avengers film without introducing Iron Man, the Hulk and Captain America first.

“Van Helsing” did this by building its story around Gabriel Van Helsing, played by Hugh Jackman, a church-sponsored monster hunter who, in the course of the film, pursues and battles Dracula and his brides, Frankenstein’s monster and a werewolf (not our old pal Larry Talbot). Like the Tom Cruise “Mummy” would be later, the film is more fighty-fighty than spooky-spooky. There’s even a Jekyll and Hyde character, something I’d forgotten in the two decades since I originally saw it. In fact, aside from Jackman’s big hat, the film was most memorable for me for Kate Beckinsdale’s thick Balkan accent as a monster-fightin’ gal, and for a scene of the heroes fighting an airborne flock of Dracula’s brides.

Universal had high hopes for the film and I did too, kinda. The studio released an expansive DVD set of the classic monster films with tie-in interviews keyed to “Van Helsing.” But the DVD set served as ominous foreshadowing of the film itself and was a mess, with some films that were listed as part of the set omitted and others duplicated. After an OK first weekend, “Van Helsing” did not survive. The reviews were not good and Jackman returned to the comparatively safe environs of “X-Men” and Broadway and “Van Helsing” would go on to be best known as cable-TV fodder.

It’s a pattern that was repeated for 2010s attempts to bring the old monsters into a new universe. “Dracula Untold” was a 2014 Universal release that dripped with Middle-Ages authenticity in its story of Dracula mostly before he was Dracula, when he was a prince devoted to his wife and son. The film has elaborate battlefield scenes and lots and lots of bats, as well as Charles Dance as an ancient vampire in a cave. Luke Evans was fine as the proto-Dracula. But for those hoping for the vampire comfort food of even “Bram Stoker’s Dracula,” it was a disappointment and Universal quickly backed away from painting it as the beginning of a new era.

“I, Frankenstein,” also from 2014, was not a Universal release and at least the studio can brag about that. The first couple of minutes recaps the creation and pursuit to the Arctic story that recent moviegoers would know from the latest incarnation of the mad doctor’s creation, but most of the movie feels like a “Highlander” retread with the creature (played by Aaron Eckhart, heavy on the eyeliner), here named Adam, fighting other hidden races of creatures. It’s very much like a different take on the “Underworld” series starring Kate Beckinsdale and is really pretty bad, with not-great action and awful dialogue like “This ends tonight!” A plot element about Doctor Frankenstein’s journal only made me think of “How I Did It” from “Young Frankenstein.”

I’m probably one of the few people who actually liked director Alex Kurtzman’s 2017 adaptation of “The Mummy,” starring Tom Cruise. A lot about it didn’t work but quite a few elements did.

I won’t go into too much detail considering you probably long ago heard enough about the film to make up your mind, but Cruise’s soldier of fortune gets to run a lot, is tossed around in an airplane and get romanced by Sofia Boutella as Ahmanet, the mummy of the title. There are callbacks to the 1999 “Mummy” – the face in the sandstorm – and even “An American Werewolf in London.” There’s Marvel and “Mission: Impossible” and “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” in the mix.

Universal had set out to rival the Marvel Cinematic Universe and chose Cruise as its first standard-bearer, along with Boutella and Russell Crowe as Henry Jekyll and Eddie Hyde. Jekyll was to be the Nick Fury of the Dark Universe, overseeing a secretive, globe-spanning effort to contain and destroy monsters. What we see of Prodigium, this universe’s version of SHIELD, is tantalizing, with vampire skulls and all manner of artifacts in glass cases in the organization’s secret headquarters under the British Museum.

I’m a sucker for world building and wish I could have seen more of this organization.

The bad reaction to “The Mummy” closed the crypt door on the big, cohesive Dark Universe, which even had its own logo and a proposed cast that not only included Cruise but Johnny Depp (apparently as a new Invisible Man) and Javier Bardem in a “Frankenstein” remake. The studio gathered the cast together for a group photo – well, at least in the sense of photoshopping the actors together to make it look they had all actually gathered. That weird lack of cohesion at the very start surely should have been a tipoff that this wasn’t gonna work. If that didn’t make it obvious, the harsh critical and moviegoer response sure did.

The new blood

In 2025, more than a century after the classic Universal monsters made their on-screen debut, the creatures live on in an unending afterlife. Through monster rallies and dark universes and exploitation and new blood, the creatures survive … in their own fashion.

Before and after the Dark Universe’s failure to launch, filmmakers and IP holders bring their own unique take on the Universal ideas, stories and characters. Before director Guillermo del Toro got a chance to make his “Frankenstein,” he hoped to remake “The Creature from the Black Lagoon.” The original film suggests the Creature’s emotional and even romantic feelings and del Toro proposed more emphasis on that element in a remake, but Universal turned him down. So instead he made “The Shape of Water,” released in 2017 to praise and awards.

The most accessible and most romantic of the monsters, “Dracula,” has seen so many iterations in recent years, turning up in “Renfield” and “The Last Voyage of the Demeter” and “Nosferatu,” hardly as romantic leading men, but compelling characters. Director Luc Besson recently made the rather straightforwardly-titled “Dracula: A Love Tale” to return to the romantic overtones of the character.

Modern-day filmmakers took two shots at adapting “The Wolfman,” first in 2010 with Benicio del Toro as the cursed Lawrence Talbot and Anthony Hopkins stepping into the Claude Rains role as the elder Talbot. Certainly the worst of the past two decades of Universal updates is “Wolf Man” from 2025, originally intended to be part of the Dark Universe series but failing in execution mostly because it telescopes the story’s timeline. If you eliminate the admittedly familiar plot point of the protagonist worrying that he’ll lose control and turn into a creature again by the light of the next full moon, you haven’t made a Wolfman movie, you’ve made a standard monster-stalking-victim movie.

Del Toro’s “Frankenstein,” gets everything right. A period piece, it is full of atmosphere and dread. There’s little I can add to the discourse of the film other than to note it so perfectly makes the creature, played by Jacob Elordi, not only attractive but sympathetic. Once we boil away all the other elements of the Universal horror films, that need to make audiences sympathize with the misbegotten creatures carries the day.