The unreliable narrator used to belong to fiction. They lived in novels and films—characters whose perception of reality was warped by trauma, ego, guilt, or desire. We were trained to read them carefully, to notice inconsistencies, to question motives, to look for what was being omitted rather than what was being said. The unreliable narrator was a warning: this voice cannot be trusted.

Then social media arrived, and suddenly we all became one.

Not because we are malicious or intentionally deceptive—though some are—but because the structure of social media all but requires unreliability. It rewards curation over contradiction, coherence over complexity, performance over truth. It turns identity into a narrative product, and narratives, by nature, select, distort, and exclude.

We are no longer just reading unreliable narrators. We are living as them.

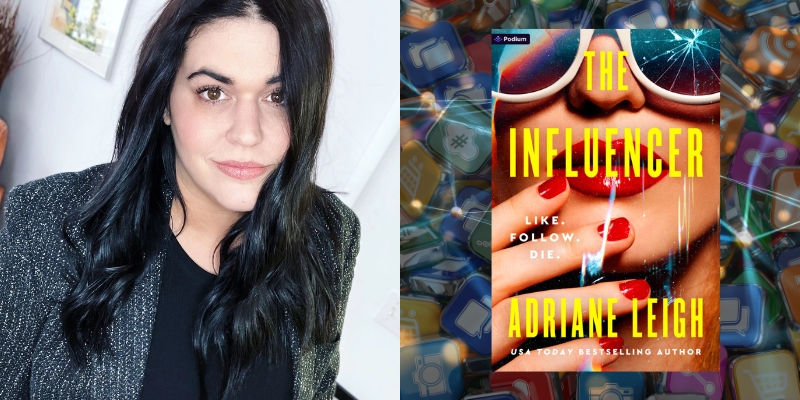

This is one of the themes I explore in my bestselling psychological thriller novel, The Influencer. Shae, a glamorous influencer, must decide how far she’s willing to go to get revenge and reclaim her life when her picture-perfect existence falls apart–all without losing any of her devoted followers.

*

Narrative Selves in a Curated World

Social media encourages us to experience our lives not as they happen, but as they will be presented. Moments are filtered through the lens of potential content. Emotions are evaluated for shareability. Experiences are edited into arcs: struggle → insight → growth. In this environment, the self becomes a story rather than a state. And stories demand consistency.

The problem is that real people are not consistent. We contradict ourselves. We regress. We behave badly for reasons that aren’t flattering. We want things we’re not proud of. But social media trains us to hide these fractures, to smooth them over, to rewrite ourselves in real time.

Over time, this produces a subtle psychological shift. We don’t just lie to others—we start editing our own memory. We remember the version of events that performed best. We forget the parts that didn’t fit the narrative. Like classic unreliable narrators, we come to believe our own omissions.

*

From Fiction to Feed

Literature has long understood that narration is power. Who tells the story controls its meaning. An unreliable narrator doesn’t just mislead the reader; they reveal how identity itself can be constructed as a defense mechanism.

Social media externalizes this process. Platforms reward those who can narrate themselves most convincingly—who can frame their lives in a way that attracts attention, sympathy, admiration, or outrage. The algorithm doesn’t care whether the story is true. It cares whether it’s engaging.

This has blurred the line between fiction and reality. Online, people adopt narrative techniques once reserved for novels: foreshadowing (“I can’t talk about this yet….”), selective flashbacks, strategic silences, cliffhangers, redemption arcs. Lives unfold episodically, with comment sections acting as audience feedback.

The result is a culture where storytelling instincts override self-awareness. People don’t ask, Is this accurate? They ask, Does this land?

*

The Self as Brand, the Brand as Lie

Once identity becomes performative, sincerity becomes aesthetic. “Authenticity” is no longer about truthfulness—it’s about tone. You can be authentic while lying, as long as the emotional delivery feels right. You can be vulnerable without being honest. You can confess without being accountable.

This is why apologies online often feel hollow. They are not expressions of remorse; they are narrative repairs. They exist to preserve the brand, not to confront reality. The unreliable narrator doesn’t deny wrongdoing—they reframe it.

Over time, people internalize this logic. They learn to experience their own emotions through the lens of audience reception. Anger is softened. Grief is beautified. Moral ambiguity is erased. The self becomes a polished protagonist who is always justified, always growing, always misunderstood.

In fiction, this kind of narrator invites skepticism. Online, it invites followers.

*

Fragmentation and the Loss of Inner Truth

Perhaps the most insidious effect of social media is not public deception, but private disconnection. When we constantly perform, we lose access to an unobserved inner life. Feelings are processed outwardly, in captions and stories, before they are understood inwardly.

This produces a strange fragmentation. There is the self you feel, the self you present, and the self that is rewarded. Over time, the rewarded self begins to dominate. You start shaping your emotions to match the version of you that receives validation.

This is the psychological core of the unreliable narrator: a gap between perception and reality that grows so wide it becomes unbridgeable, the line between reality and online persona blurs in a way that becomes psychologically destructive, with very real consequences. Shae demonstrates this in The Influencer when the ideal life she’s crafted for herself is shattered.

But instead of tears, she embraces a fierce blaze of anger, slipping into the curated role of best friend to her ex husband’s new lover–but the closer she gets to their new life the more her mental health unravels. Shae reinvents herself seamlessly because tailoring her identity to the needs of the moment is what’s required to preserve her brand. She isn’t lying because she wants to deceive; she lies because the truth no longer fits who she needs to be.

Social media doesn’t just allow this—it encourages it.

Shae’s manipulations may read as psychopathy, but the behavior itself isn’t alien—it’s just exaggerated. Social media trains us to fragment ourselves, to perform versions of identity that are palatable, profitable, and emotionally strategic. When identity becomes a brand and authenticity a tactic, the question isn’t why Shae loses herself—it’s how many of us already have.

At what point does adaptation stop being survival and start becoming mental illness?

*

Why We Believe Unreliable Stories

It would be comforting to place blame solely on creators, but audiences are complicit. We reward unreliable narrators because they offer clarity in a chaotic world. They give us heroes and villains, clean arcs, emotional resolution. They tell us what to feel and when. They even compel us to dig into our pockets and donate to causes that are sometimes just as curated as the story itself.

We say we want nuance, but we rarely engage with it. Nuance is uncomfortable. It demands patience and critical thought. Simpler stories feel safer, especially when they confirm our values or identities.

So when confronted with contradictions, many choose denial. We ignore red flags. We excuse inconsistencies. We protect the narrative because it serves us. In this way, unreliable narration becomes a collective act.

*

Reading Carefully Again

In literature, the unreliable narrator teaches us to read between the lines. To ask: What is missing? What isn’t being said? Who benefits from this version of events?

Those same skills are urgently needed now—not just as readers, but as participants in digital life.

This doesn’t mean abandoning storytelling or self-expression. Humans need narrative. But it does mean resisting the urge to turn ourselves into flawless protagonists. It means allowing ourselves to be contradictory, unfinished, and unseen.

The most radical act in the age of social media may be refusing to narrate everything. To let experiences remain private. To allow the self to be messy without explanation.

Because the danger of the unreliable narrator is not that they lie to others.

It’s that, eventually–as in the case of Shae–they forget how to tell the truth to themselves.

***