Listen. This actually happened to the friend of my cousin’s cousin. It was years ago, mind, way before we had the internet or mobile phones, so you have to bear that in mind. And it happened in the States – you know they have big houses out there, houses with big gardens, set back from the road. Anyway. This girl, she’s sixteen, she’s babysitting for her neighbours’ kids. It’s late, so the children are in bed, and she’s sitting up getting some homework done, when the phone rings – someone is calling the landline. She answers it, expecting a parent checking up on her, but all she gets is a man’s voice. She doesn’t know him. He says, ‘have you checked on the kids?’. Our girl slams the phone down, annoyed and a little freaked out by the prank call. She goes back to her work. And then, a few minutes later, another call. ‘Have you checked on the kids?’ This time she calls him every name under the sun, but there’s nothing else from him but heavy breathing. After the third call, she puts the phone down and calls the police. The police are sceptical, but they say they will trace the call if it happens again. Our girl waits, rigid with a mixture of fear and anger, until the caller rings again. ‘Have you checked on the kids?’ This time, the second she slams the phone down it rings again. The police are on the phone, and they no longer sound so sceptical. ‘You have to get out of there,’ they tell her. ‘The calls are coming from inside the house.’

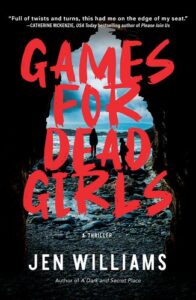

Now you probably know this story, or a story very like it (perhaps you know my favourite version, where the sitter complains to the parents over the phone about the weird lifelike clown statue in their front room, and of course the father replies: ‘we don’t have a clown statue…’). It’s an urban legend, a story passed from person to person, often with the ‘this happened to a friend of a friend’ tag. They can be scary, and they usually carry a warning and almost certainly a twist. When I was a kid I was obsessed with these sorts of stories, and when I started writing Games for Dead Girls – a book that partly follows a ten year old girl during one fateful summer in 1989 – I took a lot of myself at that age and put it into Charlotte Watts, a girl with an overly active imagination and a morbid fascination with scary things.

And they remain fascinating to me, these raw little morality tales; these virus-like stories that jump from person to person. For a start, many have their seeds in true crime. The story of the babysitter menaced by murderous phone calls, for example, is widely thought to have sprung up after the horrific murder of thirteen-year-old Janett Christman from Missouri, who was managed to call the police during the attack that killed her, only for them to listen helplessly as she screamed for her life.

The virus can jump the other way too, evolving from a story shared at a sleepover to a story shared on the cinema screen: I imagine a lot of people my age will read the babysitter story above and think of the first Scream movie where, in the iconic opening sequence, Drew Barrymore is teased and then slaughtered by a frightening presence on the other end of the line. In fact, the babysitter story has popped up in different forms in a number of films, perhaps most notably 1979’s A Stranger Calls, which uses the story to form its opening act.

The relationship between urban legend, authored fiction and true crime is often too complex to unpick. To muddy the waters even further, consider the case of The Slender Man. Back in the dark old days of the internet (2009), Slender Man was created as part of a photoshop challenge, where users of the Something Awful forum were tasked with creating ‘paranormal images’. Eric Knudsen submitted two black and white photos featuring a looming shape in the background, a faceless, impossibly tall creature – and so Slender Man was born. Something about the image and the little scraps of story Knudsen provided, fired user’s imaginations, and soon Slender Man’s story and mythos began to grow. It makes sense, of course, that the internet is the perfect breeding ground for stories that exist in a limbo state between the real and the imagined – over the last decade we’ve all experienced the consequences of, for the want of a better phrase, ‘fake news’. Slender Man’s story grew and warped and changed as it moved around the internet, eventually resulting in a film, a video game, and unfortunately, a real world murder attempt. In 2012 in Wisconsin, two twelve-year-old girls lured a friend into the woods with the intention of stabbing her to death in tribute to the Slender Man. Thankfully, despite being stabbed nineteen times and left for dead, their victim survived, managing to crawl to the road to get help. It’s arguable that people as disturbed and mentally ill as the two girls involved would have followed any mythical figure down that particular dark path, but it is an example of how much impact a creepy little story can have. And it’s blurring the lines again between fiction, true crime, and horror.

The Slender Man mythos and all its complicated fallout was a source of inspiration for Games for Dead Girls. In my novel, two girls create their own imaginary monster called Stitch Face Sue, a vengeful figure with a tragic past (based in ‘real’ history) and their enthusiasm for the creature – in itself born out of a need to try and have control over their own lives – has disastrous consequences. Like Clive Barker’s iconic Candyman figure (originally appearing in the short story ‘The Forbidden’), Stitch Face Sue also has her roots in Bloody Mary, an urban legend that was also a kind of game. Say her name three times into a mirror and Bloody Mary will appear – to kill you? Curse you? Answer your questions? I heard different versions of this story growing up, and I never failed to be creeped out by it; and, inevitably, compelled by it.

I think the reason that urban legends continue to fascinate is that they are one of the clearest signs that storytelling is as vital to human beings as breathing. Even if you don’t write for a living, or make movies, or create comic books, you’ve probably passed on a story like the Babysitter, or the Car Door and the Hook, or the Killer on the Back Seat – you’ve whispered them in playgrounds, by water coolers, over dinner. You probably knew it wasn’t entirely true, but the telling of it was just too delicious to resist. Ultimately, human beings communicate with stories, we pass on information and warnings and jokes in this format and have done so for as long as we’ve been around. And in the end, sharing that little shiver of horrified realisation is worth bending a few truths.

***