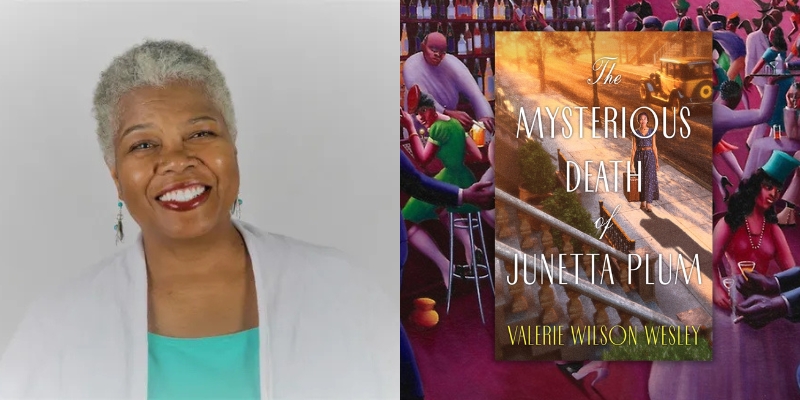

For decades, Valerie Wilson Wesley has been a noted journalist, the author of many books for children and adults, including the award-winning and beloved Tamara Hayle mystery series. More recently she wrote the Odessa Jones mystery series, but as I told her when we spoke recently, her new book, The Mysterious Death of Junetta Plum, might her best book to date.

The book opens with twenty-six-year old Harriet Tubman Stone leaving her home for Harlem, after a cousin she’s never met reached out. Harriet’s father and fiancee died recently, after losing her mother, brother, and others to the Spanish Flu Pandemic. Harriet brings with her Lovey, the orphaned biracial twelve year old daughter of a childhood friend who died in the Pandemic. The book captures some of that tentative joy and fear of youth and moving to a new place, that sense of wonder and reinvention, and captures some of what 1926 Harlem might have been like.

The novel, which is out now from Kensington Books, is as Wesley admitted in our conversation, a departure. She talked openly about the challenges and the joys of writing something different—and difficult—in her late seventies. What was interesting as a reader was how the book felt so contemporary in many ways, framing it as a post-pandemic novel.

Beyond Covid, Wesley spoke about how she saw some of her own youth in the 1960s and 1970s in understanding the Harlem Renaissance, and about the responsibility to the people of this period in writing about it, especially at a time when some people seek to erase history.

*

Alex Dueben: I’ve read many of your books and I know you’ve written many books for children and adults, but have you ever written a historical novel prior to this?

Valerie Wilson Wesley: No. This is my first one.

AD: You made a joke before we started about not being a spring chicken anymore. What made you go, I want to do something new and totally different from what I’ve done before, that’s also really hard?

VWW: It is hard. At one point I went, I think I said this in the author’s note, have I lost my mind? [laughs] Why am I doing this crazy thing? The reality is that I am my late seventies and you have to take chances. You have to say, this is something I’ve always wanted to do.

The very first book I wrote was not published. It was a YA novel about Reconstruction. I will someday maybe go back to that. I’ve always loved history. I like to research. As a former journalist, I enjoy researching. And once you start, you keep going with it.

I love to write, and I love mysteries. It’s scary, because you check and double check again and again, to make sure you have all the historical facts straight. I’m sure at some point I made mistakes, but you do the best you can do. Of course with a series, you’re going on to different parts of this particular period.

I really am enjoying this. I loved writing Tamara Hayle, I loved my cozies, but they’re so very different books. I think they bring out different parts of me as a writer. That’s been fun, at this age discovering that I have other things, other ways, other places I can go.

AD: The book is mostly set in mostly Harlem in 1926. Was writing about this place and time part of your initial idea for this book?

VWW: That period is fascinating. When you start right around the 1920s, so many things were happening. This is why in the book, there was a whole page of historical facts.

AD: How did you phrase it, “Key historical influences?”

VWW: There were so many things that each of the characters has been influenced by in some ways. With Harriet born in 1900, so many things impacted her life. The First World War. The Spanish flu. In terms of Black history, the Civil War, of course was over, but Reconstruction affected so many of the older characters. Jim Crow coming in right after that. So many things touched people’s lives. Trying to imagine what it would be like to be a character during this period.

In some ways, I could reach in my present and see what it was like in the characters’ pasts. That has been interesting, too. I also liked the idea of Lovey, Having a biracial child during that period, and what that would be like, because of all the things that she would have to deal with. She’s a delightful character, who I like a lot.

AD: I like her, too. And you make a point of framing this book and this period, as a post-pandemic story, and thinking about it in those terms.

VWW: People just wanted to live. I think in some ways, the Harlem Renaissance was a response to all that. Saying, we are claiming our lives for ourselves. People who were writing during that period, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, all of those writers were basically around the same age as Harriet. Seeing what it would be like to have been in a young person in that period. She’s twenty-six. I made her birthday 1900, because I’m so bad at any kind of math. [laughs]

That was a way of understanding that period, too. Reading their work, and just seeing the excitement during that period. It’s similar to the period that I was in during the 1960s, when there were so many things happening and so much reclaiming of who you were, and self-definition. They’re very similar in that way.

In some ways, I still have a sense of what it would be like to be young in that period. Then of course, there’s so many historical facts that you discover. Woodrow Wilson’s firing all those people. The Klan rock marching through. Harriet Tubman’s funeral, which Harriet’s father attended. All of these little facts that I discovered, that found their way into the book. That’s the fun of writing about this period.

AD: It was such an exciting period where where so much was happening. And as you said, so much, the Civil War, Reconstruction, Enslavement, weren’t history, they were all still living memory.

VWW: That was it. People were looking for families. People were looking for people. The more I read, and the more I continue to read about this period, the whole historical events that were happening, the more it gives me ideas for characters. Can I bring this into the book somehow?

Of course, the limit is you’re writing a mystery. So you can’t get carried away with the history. You want to be fair to the genre, too. That’s why I love writing this. I don’t want to say it’s been fun, because I’m plowing away at the second book, and it is no fun. [laughs] But I must say that it’s been rewarding in ways that I found surprising.

AD: There’s a passage at the bottom of page four, that jumped out at me on the first reading and, and on rereading: “My friends who had lived through the plague and the war were hungry for life and felt it owed them a slice. Grief curtailed my appetite, leaving me in the past. Until one momentous day, I realized I was the only woman on the street whose skirt hit her three inches below her knees.”

VWW: I thought when I wrote that, oh, that’s what it would be like. Going, oh my god, I’m old. Look at me. [laughs]

AD: It’s such an elegant image and an emotional gut punch. Besides signaling to a careful reader that they are in the hands of a good writer, it’s a very good way into the story and to this character, who has been dealing with so much loss.

VWW: Thank you. This is the exploration of who she is and finding her own life within this period. And of course, there’s Lovey. Harriet is kind of a mother, but she’s not. As Lovey often tells her. She’s also suffering. A child would be going through this as well. My daughters are grown now, but all of these things affect children in different ways.

In the second book, I explore that a little bit more with Lovey’s loss. My grandson was reading The Great Gatsby and I was reading it with him, and I said, this is what she’d be reading probably during that period. Because it was short and everyone was talking about it. She says, gee, I’ve been sitting on my porch in Hartford and life is going by. People are celebrating. Her father’s death, of course, puts her in that space.

AD: We’ll never really run out of superlatives for the Harlem Renaissance because there’s just so much work by so many people, which are still so good.

VWW: I know. Picking up and reading The New Negro again, looking at all the essays and the drawings. Goodness knows that you don’t have the time. Like I said, I’m not a historian. I had to be careful because I had a deadline. Looking at the old drawings of Penn Station, I had a whole page describing that. I thought, I can’t have this. Nobody cares about this. [laughs]

I had to cut that out. Those are the things that for me, writing in this new sub-genre of historical fiction, are completely new, and a different way of writing and the research that goes into it.That’s been at this point in my life, really exciting to do.

AD: The way you have Harriet experiencing and understanding this, I kept thinking that this is how most people would have experienced and understood the Harlem Renaissance.

VWW: In the second book there’s a poem that I’ve always loved by Langston Hughes called When Susanna Jones Wears Red. I couldn’t fit it in this first book, but I have done it in the second book. I just had to find a way to put it in the dialogue because I love this poem so much. I don’t know if it would work, but this is where as a writer you say, I don’t know if this is going to work, but you try it and you see, because I love the poem.

Little things like that were fun to do. The respect I have for these writers and what they were writing and all of the things that folks were doing. And the barriers that were stopping them. There was a magazine they put out called Fire, which burned. [laughs] I had to put that in the second book. I felt a little freer in the second book, because the characters were established so I could play a little bit more, but I had to find a way to fit that into dialogue.

Stuff like that has made writing about this period interesting. Hopefully I’ll keep doing that in the third book, and after that, we’ll see if I’m still around. [laughs]

AD: There’s also so many beautiful little details you throw in. Like Harriet makes a comment about the Cotton Club, because that’s something that most people then—and most contemporary readers—would know. But she’s told, no, younger guys won’t play anywhere we’re not allowed to sit.

VWW: That’s true. They didn’t play there. I mean, respect to Duke Ellington, because you had to make a living. The younger guys didn’t have to do that.

AD: You convey that there’s so much going on, and as much as Harriet is excited by it and interested in it, even living in Harlem, she’s not aware of how much is going on.

VWW: It’s different world. That’s part of the joy of it, discovering things for myself. As I keep talking about this book I’m working on, which let’s talk about this one. I don’t know if I remember I mentioned the Hotel Olga in this first book.

AD: I don’t think so.

VWW: Another thing that I discovered in research, is this extraordinary hotel. That no one’s ever heard of. It was really an elegant hotel. I think it was Lennox and 145th or something. I’d never heard of this hotel, and it was a very important hotel apparently in Harlem during that period. It was razed, I think, in the 1960s.

Little bits of information like that, that the more you research, you want to find ways to use it. It enriches my sense and my mind for the characters and who they are. That’s what I’ve been playing with. Which is one reason, again, why the book has been so interesting to write.

And exhausting. It’s tiring. I write about five hours a day with breaks, because I have arthritis. I’ll do some stretches. I have dinner to cook at some point. You find the time, but it’s tiring. I find that I’m tired after writing, but I get up the next morning, and I’m excited to get back to it. I want to go back and live in these characters. This has been fun.

One thing with the Tamara Hayles, there was violence in those books. There was a lot. That’s hard to write. There was one book that had a particularly violent ending, and I was like, I can’t. This is bad. I have to burn something to get rid of these spirits. Just going into the minds of these murderers. With this book, you have a certain sadness.

AD: As you were saying that, I feel like so many of the killers you’ve written about are sad. They’re not—well, they are clearly psychopathic—but there’s also this sadness, which led to that, or sort of sat alongside this violence.

VWW: Thank you for recognizing and mentioning that. Because you write the protagonist, of course, and next comes the killer. You have to understand who that person is, in order to fit him or her in and out of the book. You have to have red herrings and all the other stuff that mysteries need because you can’t know right away who’s the killer.

But you have to know who is this person. For me, you really have to explore them because the killer is as important as anybody else. More important, really, because there’s a reason he or she has done this. Throughout the book, I try to hint that there are things that aren’t quite right, but you excuse it.

This is another thing that I tried to play with a little bit the idea, this sense of young woman, if they’ve lost a parent or a mother will sometimes look towards older women as mentors. You better be careful who you do, because sometimes that mentor is not who you think she is. That too, is a lesson that Harriet learns. Not everyone is what they seem.

This is an important lesson for Harriet, because she has grown up in a fairly protected environment with her father, her family, and that community in Hartford. Facing Harlem in the middle of New York is crazy. All of this is part of what she learns, and who she becomes. The question of the books is more and more, she finds herself. We’ll see what happens.

AD: Lovey is still too young to kind of grasp all of this, but similarly, women who have lost a child, or who couldn’t have children, are drawn to her.

VWW: I say in the acknowledgments that she was kind of inspired by my grandniece. We were on a cruise. Poor thing. [laughs] She ended up on a cruise from hell with all these senior people. And there was her. She kept saying, I just want to go home. We’re in the middle of the Mediterranean, you can’t go home. [laughs]

Ultimately, she’s a very smart girl. We wanted her to go in with this other teenager. She didn’t want to do that. She ended up in the ship’s library, if you can believe that, every day. She would read and she’d come back to the table and regale everybody with what she’d read. I said, this is Lovey. The sense of not being an adult, but not being a completely a child, and the sophistication, but not really sophisticated.

I had to mention that and pay my tribute to to Kaia because I remember what that was like to be twelve. I remembered on that horrible cruise. I thought, this is so much like Lovey. I’d written her before, but on the cruise it gave me insight into what that would be like. She grows too in the books. Being a teenager, but also being a biracial teenager. Where do you fit? Where do you fit anywhere in the world as a teenager? And of course, leaving Hartford.

It’s all part of what I hope will give a richness to the characters and levels to the characters within their historical time. I’ve tried to do that.

AD: You talked a little in the author’s note about some of the research you were doing. I wonder if you could just talk a little about that. I know research leads you down a million different paths, but it sounded like this encompassed a lot of historical and genealogical research.

VWW: What happened was a couple of years ago, someone called my sister and said, we have your great-great-great aunt. Her name was Candace. To make a long story very short, we found out, as I say in the book, that she was a part of this town, Guilford, Connecticut. I always wondered why my father chose Connecticut, of all places to go. He had his roots there, though he never really shared it with us.

The more research Pat did, the more she shared with me. The Witness Stones Project is based upon the original Witness Stones for Holocaust victims, whose deaths were covered up and not acknowledged. These are for enslaved people in Connecticut and New England and it’s based upon that idea. The more my sister Pat found out, the more she became excited about it. She’s now involved in the project even more deeply.

Understanding more about that part of me also made me understand how you don’t know until you really begin to research how deeply you are in a place. My ancestor Sharper Rogers fought in the Revolutionary War. This was something that we didn’t know.

I say in the book, look for your own roots. Try to find out where they fit during this period. I think it gives you more of a sense of yourself as part of this country.

I’m watching Ken Burns’ The American Revolution, which is an extraordinary piece, and just brings everybody in. You understand this is a country of many different people and different places and different ideas. It makes it a far more beautiful country than we sometimes realize. I wanted to give that sense. That we are many things, and each of us has an individual story within that.

Getting involved in history and understanding history deepens your feeling of yourself and your place where you belong. This is my country, too. You can’t think that it’s just one people. It’s many, many. These are things that are really important to me but I hadn’t realized that until Pat shared it. My father was a Tuskegee Airman, which I’d never heard of as a child, but it’s a major thing.

AD: It’s a huge thing.

VWW: And some of the local people realized it. I remember when he died one of the guys said how this is a major thing. I hadn’t realized how important it was. He had these medals. These are things that matter. Sometimes we don’t realize how much we have at stake here. This is one of the things I wanted to touch on in the book. Not hammer it down, just, be aware of these things.

AD: Writing a book set one hundred years in the past that’s in part about those deep roots, that is very relatable to the present, it definitely conveys that.

VWW: That has been very rewarding. The more you write, the more you research, the more you want to put things in. But you’re writing a mystery, so you can’t lose sight of the pacing of it and the rhythm. I like to cook, not as much as I did when I was younger, but I wanted the recipes in there. [laughs] That was fun. People always asked in the cozies, what about the recipes? The publisher likes it, too.

AD: There’s so many great little details about how so much is changing. Like you mention Lovey going to the children’s room at the library, and you could spend chapters writing about that.

VWW: It’s endless.

AD: It’s an amazing period and you really do convey that.

VWW: You want to do it justice. The people who lived during that period, you want to give them their dues. As much as you possibly can. That’s the bottom line. Do the best you can possibly do.You owe them that. You do. And you owe the readers that. That means checking and double checking, and then I had someone fact check things as well. But you miss stuff. [laughs] Hopefully nothing jumps out. You want to get it right. As right as you can possibly get it.

These people are looking down going, honey, you better get this right, because we died for this. We have to talk about what happened, otherwise it’s so easily erased.

Look at what’s happening now. You just say, I have to make sure that I get this right. As right as I can physically and emotionally and mentally get it without killing myself in the process. Because this is what will stand. There has to be some truth against the falsehoods that are perpetuated. It’s easy to erase history, as we know. It’s easy. I’ve done my part to save what I can.

***