On March 26, 1925, during a Commons session, Mr. Cecil Wilson raised an eyebrow-raising question: why were so many women in prison repeat offenders? In fact, 2,886 women had been convicted more than twenty times that year. What is more, many of these habitual criminals were elderly. Harmless while locked up, they became petty thieves or hawkers the moment they were freed, their lives a revolving door of incarceration.

Wilson, in a stroke of compassionate genius, suggested that perhaps these women were feeble-minded and ought to be handled differently rather than being endlessly recycled through the expense of the prison system.

Feeble-minded? Bit of a stretch given no pensions or welfare and surviving the cold streets. Desperation? Perhaps. But when facing starvation or a roof over your head, prison seems like a solid strategy.

The Lambeth Riot

Roll on January 1926 when a different set of women altogether found themselves up at The Old Bailey on charges of inciting a riot in an event that became known as The Lambeth Riot. The previous December, a drunken mob had marched up on a family home near The Cut in Southwark. What happened can only be described as frightening violence and intimidation, bordering on attempted murder.

It is a long and complicated story, it always is. But while men had been the ones to administer much of the violence, breaking into the house itself to settle old scores. It was women at the helm. Specifically, Queen Alice Diamond, the leader of the infamous female gang of professional thieves, The Forty Elephants.

The Forty Elephants

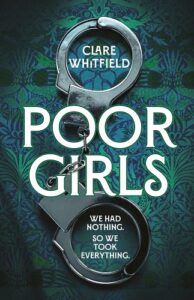

When I set out to write a fictional novel based on The Forty Elephants, I realized when I shared this idea with friends some seemed apprehensive of lending compassion to characters who were unashamedly criminal. Yet could thoughtlessly indulge in gangster films without thought.

It was as if it was morally wrong to shine a light on such women. It was not romantic, it wasn’t pretty. It felt… uncomfortable. We should be focusing on shining examples of womanhood, not highlighting the worst of our kind. But I don’t see it like that at all.

There was even a sense that the characters must fit into binary buckets; one labelled ‘desperate’ the other ‘empowered.’ As if such wicked women, if filtered through palatable sieves of simplicity, might make it acceptable. It would be ‘ok.’

This morality hoop we expect women to leap through intrigues me. I write about complex female characters, and I’ve been asked why I appear obsessed with criminality in women. I hesitate to justify this because I’m not sure why I should. Why we need to see criminal women through the lenses of desperation or empowerment is the more fascinating question to me. What does this say about us?

Victim or… Monster?

We are comfortable with the depiction of women as powerless prey. We have grown desensitised to endless headlines of yet another murdered woman. A brutally violated woman, a woman murdered by her partner. We don’t react much more than a sympathetic nod of ‘it’s awful, isn’t it?.’ And we move on. We are used to this happening. Its normal.

When it comes to a woman being the perpetrator of a crime, we try and assign them into the victim bucket. We see it as a compassionate act. An abused woman driven to do terrible things out of self-defence and against her natural nature to be passive. It’s hard to deny we seem addicted to fetishising female criminals into simple caricatures.

We want to pity (victim) or admire (angel) but both facilitate permission to ‘like’ these women. Do people sit around when devising the next TV series about Pablo Escobar or The Krays, tearing themselves apart, asking… ‘But is he likable though?’ What a chain?! The perennial albatross around the neck to be likeable at all times.

Besides who said Alice Diamond wasn’t liked? She had plenty of friends. Doesn’t a diamond have many facets? Can’t Alice, and the characters in my stories, have nuance. Can they not be at once, funny and do bad things? Can’t they be complicated, you know, human?

Female Rage

Alice Diamond stood five feet nine at a time when average height for a man was five feet six inches. Most women can’t punch a man and make him see stars. Alice could, that’s why the police called her Diamond Alice. Now not many women will take on a man in a fist fight. We wouldn’t go toe to toe with a man, that’s insane. A female murderer may carry the same malice, but she’ll wait until her prey is asleep and get him that way. She’ll poison his food. Or manipulate another man to do the toe to toe stuff for her. She wants to win.

That premise starts to sound like empowerment, but I reject that bucket with even more ferocity. I find the empowerment tag weirdly condescending. It’s got that girl power twee vibe. As if dreamed up by a marketing team after running a focus group on positive words no one can disagree with. It erases the victims of crime. The loss of property, the scars and violence. The harm.

The Forties weren’t above doing terrible things because they were women. Intimidating witnesses, blackmail and extortion is not harmless. But it was dog eat dog in 1920s Britain and what do you expect a clever, vibrant but poverty-stricken young woman to do? Sit around and wait to be eaten? Actually yes, I think as a society we often do expect exactly that.

Man vs Bear

One aspect of the Man or Bear story that no one asks is if that bear is a lady. Of course not! That’s irrelevant. We assume both genders of bear may wish to eat us. From the viewpoint of a different species, we don’t make silly cultural assumptions about the differences between girl and boy bears. We understand that they are fundamentally the same species with the same instincts. We don’t think: ‘Well if it’s a girl bear, she’ll be helpful and smiley.’ Do we? And yet we do this with humans, you’d have thought we’d have learned by now.

Women crave adventure and excitement too. Young girls dream of spending money and having experiences and the most driven simply can’t sit back and wait for the next thing to happen to them…. What even is that state? Perpetual victimhood?

And we’ve come full circle … Because that’s what’s expected of women much of the time and women are as much at fault for this, because we often demand this passivity of each other.

If we find ourselves intrigued by the exploits of The Forty Elephants and desperate to exonerate them to fit into our expectations, to make them likeable. Should we be asking? Why do I have such crazy expectations that women should be morally faultless? Let them be hard to pin down, resist the buckets! Let us all be human.

***