Twenty years after the job of “detective” was established in Britain, via the Criminal Investigation Division of the New Metropolitan Police in 1842, detectives began appearing on the stage. According to scholar Kyle R. Deise, in Britain, the first official detective character on theatrical record is from The Ticket-of-Leave-Man in 1863. The play inspired several illegitimate sequels, including two that same year: The Detective, or A Ticket-of-Leave by C. H. Hazlewood and The Return of a Ticket-of-Leave (author unknown). Like many plays produced in the Victorian era, The Ticket-of-Leave Man was itself an adaptation of a French play, which Taylor rewrote in two weeks for a total sum of £200; Isabel Stowell-Kaplan notes that it was based on the drama Léonard, ou Le Retour de Melun (1860) by Edouard Brisebarre and Eugene Nuz—which owed much, in turn, to Eugène-François Vidocq’s highly popular memoirs, published in France from 1828 to 1829 and hastily translated to English.

Vidocq—a former criminal who, in 1813, established France’s first criminological investigative bureau, the Sûreté nationale—was an extraordinarily popular figure on both sides of the Channel. In 1829, in Britain, there were two separate theatrical adaptations of his memoirs, including Douglas Jerrold’s Vidocq! The French Police Spy and John Baldwin Buckstone’s Vidocq, The French Police Spy. Another adaptation, by Frederick Marchant, was produced in London in 1863, the same year as The Ticket-of-Leave Man. Although the detective would not officially arrive on the British stage until the midcentury, the early curiosity for stories about Vidocq, a dashing proto detective, contextualizes the impending explosion of detective characters in several forms of entertainment.

Tom Taylor wrote a second play featuring a detective, the romantic drama Mary Warner, in 1869. Dion Boucicault prominently included detectives in his melodramas Foul Play (1868) and Presumptive Evidence (1869), as well as in his American play The Shaughraun (1874). Other detective plays included G. B. Ellis’s The Female Detective (1865), William Travers’s The Boy Detective (1867), Clement Scott’s The Detective (1875), Henry Arthur Jones’s The Silver King (1881), Mark Melford’s The Secrets of the Police (1886) and E. Stockton and E. V. Hudson’s Handcuffs (1893). Detectives also appear in Watts Phillips’s Maude’s Peril (1867), and W.S. Gilbert’s A Sensation Novel (1871).

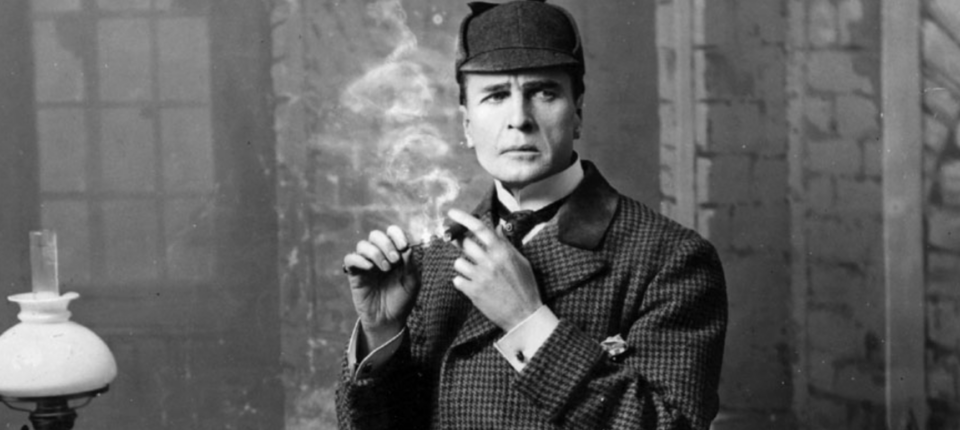

Detective novels were also commonly adapted for the stage during this time. Bleak House found itself a great many theatrical versions—often, as in the case of Henry A. Rendle’s 1875 melodrama Chesney Wold, John Pringle Burnett’s 1876 melodrama Jo, and George Lander’s Bleak House, or Poor Jo in 1876, centering different characters than the novel. Wilkie Collins, who adapted eight of his own novels into plays, dramatized his mysteries more than any other genre: No Name (twice, in 1863 and 1870), Armadale (once in 1866, and once as entitled Miss Gwilt in 1875), The Woman in White (1871), and The Moonstone (1877). (Collins’s prolific playwriting was likely motivated by the desire to retain theatrical copyright, after a pirated production of The Woman in White played at London’s Surrey Theater just ten weeks after the novel concluded serialization in 1860.) And in 1899, William Gillette would produce and star in his adaptation of the Sherlock Holmes stories, with permission from Arthur Conan Doyle.

Until Gillette’s Holmes, the most significant of any of these plays was The Ticket-of-Leave Man, which burst onto the scene, satiating the evident demand within the British public for a true detective play. It broke records with its run of 407 nights at London’s Olympic Theatre in 1863. In the play, a young countryman named Robert “Bob” Brierly—new to London—is accidentally embroiled in a counterfeiting scheme that is swiftly busted by the world-class plainclothes police inspector and master of disguise, Detective Jack Hawkshaw.

Though Brierly is innocent, Hawkshaw arrests him. Several years later, Brierly returns from his prison sentence a “ticket-of-leave man” (a parolee). He’s hardworking, world-weary, and thirsty for justice—discovering a chance to avenge his past when Hawkshaw reenters his life. Hawkshaw is intent on capturing the same counterfeiters who had gotten away before and are now attempting to pull off a burglary, but his comeback is motivated by personal vengeance as well: it is revealed that one of the criminals, the sinister Jem “Tiger” Dalton, had been responsible for both the mental deterioration and slow death of Hawkshaw’s dear friend Joe Skirritt. Thus, Hawkshaw and Brierly join forces, infiltrating the counterfeiting ring to bring down the criminals at last.

There has been relatively little scholarship focusing on the nineteenth-century detective play. The Ticket-of-Leave Man and the character of Hawkshaw have received more attention than most, but overall the genre is still relatively unexplored. In 1940, Winton Tolles produced an annotated edition of Tom Taylor’s plays, which featured an essay glossing The Ticket-of-Leave Man’s place in Victorian culture. In 1985, Martin Banham annotated a collection of four Tom Taylor plays, analyzing, in his introduction, Hawkshaw as the progenitor of the modern, logical detective character who would persist through the twentieth century.

Banham attributed this phenomenon largely to the performance of Horace Wigan, who played Hawkshaw, and who “set a pattern, together with the playwright, for the stage detective who was so to fascinate audiences throughout the rest of the nineteenth century and indeed to the present day.” Shortly thereafter, David Mayer wrote an article cautioning those inclined to read Hawkshaw outside of his Victorian context or even as “a respected instrument of public justice.” Reminding his readers that Victorian culture was generally hesitant towards embracing detective figures like Hawkshaw (and even Vidocq, despite his popularity), Mayer notes that the widespread anxiety about plainclothes police was partially due to reports of French “agent[s] provocateur[s],” who would coerce individuals to break the law and subsequently catch them in the act.

He therefore underscores that Hawkshaw’s first appearance in The Ticket-of-Leave Man is as an apprehender of the unlucky Brierly, and explains how this dimension of the play captures a wide spectrum of police impact (including very negative effects), and would have encouraged Victorian audiences to consider varied responses towards such a figure and that figure’s potential impact on real-life society. These concerns about authoritarianism were already in the air; just one year after The Ticket-of-Leave Man premiered, Parliament enacted the Penal Servitude Act of 1864, extending the prison sentence of first-offenders (like Brierly) to five years, instead of three.

___________________________________

This essay has been excerpted from The Performing Detective: Spectacle and Investigation in Victorian Literature and Theater, by Olivia Rutigliano. Copyright Olivia Rutigliano 2023.