For all the posthumous praise heaped on the novels and essays of Harlem born author James Baldwin, early in his career he could be quite a hater when it came to the writings of his fellow soul brothers. In addition to smearing the name of mentor, money lending pal and Native Son scribe Richard Wright in his infamous essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” published in 1947, that same year Baldwin also dismissed the writings of author Chester Himes. Reviewing Himes’ second novel Lonely Crusade for the New Leader, Baldwin claimed the author wrote, “Probably the most uninteresting and awkward prose I have read in recent years,” and, “Himes seems capable of some of the worst writings this side of the Atlantic.”

Still, as Himes pointed out to Black World magazine editor Hoyt W. Fuller in 1972, Baldwin wasn’t alone in his scorn of the book. “Everybody disliked Lonely Crusade,” Himes said. “The Blacks disliked it, the whites disliked it, the Communists ran an assault on it, the reactionaries disliked it, the Jews disliked it; everybody.” Although such furious reaction to their work might’ve driven a weaker writer to choose another career, Himes was often fueled by the hatred of others as well as his own. In his lifetime, Himes might’ve given up on college, women and trying to be a nice guy, but he never quit writing.

Certainly, the light of the written word had guided him through some dark times, and it would take more than a few bad reviews to deter him from his literary mission. Himes would go on to publish a few more mainstream novels, including the prison-based Cast the First Stone (1952) and the sexually charged interracial coupling of The End of the Primitive (1955), but none had made him richer or more respected. Leaving America in 1953 because of the racism that treated him as “less than a man” in addition to his lack of monetary success, Himes relocated to Paris, where he joined buddy Richard Wright and cartoonist Ollie Harrington at the Café Tournon. It was there that the men drank, debated and played pinball. However, Himes was also becoming increasingly unhappy with his hand-to-mouth existence and decided he needed to do something drastic.

In December, 1955 when Himes was forty-six, he met with Marcel Duhamel, an editor from the Parisian publisher Gallimard. Duhamel had translated Himes’ debut If He Hollers Let Him Go a few years before, but was now serving as an editor for the crime fiction series La Série Noire. He invited Himes to contribute a novel. According to The Several Lives of Chester Himes by Edward Margolies and Michel Fabre, “Himes protested that he didn’t know how. “It might not be that difficult,” Duhamel said. “Start with a bizarre incident, any bizarre incident, and see where it takes you. As for style, follow the example of Hammett and Chandler: avoid excessive exposition, avoid introspective characters and employ dialogue to convey movement. Above all, include action.”

Himes’ own violent past, which included a wild adolescence in the world of vice as well as a seven and a half year stint in prison that began when he was nineteen, came in handy as reference for his violent fictional world populated with weirdly named characters (Easy Money, Pinky, Uncle Saint, and Sister Heavenly) and motored by strange plot twists. In a letter to his friend and fellow writer John Williams in 1962, Himes stated that Duhamel offered him a thousand bucks advance.

“Naturally, I jumped at the chance. I knocked the first one out in about nine or ten weeks—then I could live again. After that, it took four or five weeks to write one.” Those books, three which have been made in films, changed the course of Himes’ life and, in many ways, redefined his legacy from minor to major.

***

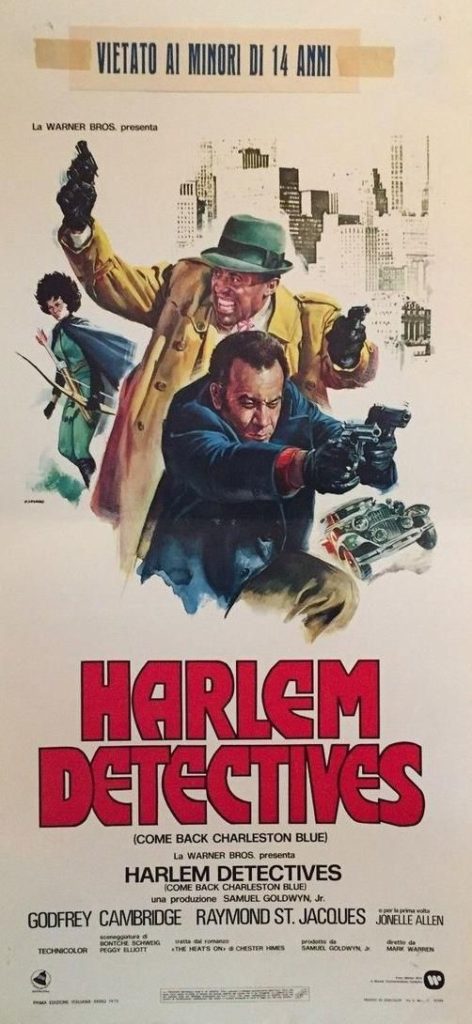

My introduction to Himes’ work was not through the books, but the 1970 proto-blaxploitation film Cotton Comes to Harlem and its sequel Come Back, Charleston Blue, based on The Heat’s On and released in 1972. Still, it wasn’t until a decade later when British publisher Allison & Busby began reprinting Himes’ novels that I discovered the writer that would soon become my hard-boiled hero. Using the mind-blowing Harlem themed paintings of Edward Burra to illustrate the covers, Himes soon became a favorite noir writer whose work was gritty enough to be mentioned in the same breath as Jim Thompson and David Goodis.

As though under a spell, I read the books quickly and for the first time realized that “the black experience” books of Iceberg Slim, Donald Goines and Nathan C. Heard had a forefather. In the sixties and seventies, Himes books also inspired literary writers including Amiri Baraka, Ishmael Reed and William Melvin Kelley. These days his influence can be seen (felt) in the writings of Megan Abbott, Joe R. Lansdale, Nelson George, Ken Bruen, Darius James, Gary Phillips and Charlotte Carter, author of the Nanette Jones mystery series that began with Rhode Island Red in 1997. “Although he began his career as a literary writer, there wasn’t an ounce of pretension in his stuff,” Carter told me last year. “Himes was a fantastic writer, but he always came across as a very tortured man.”

Himes famously wrote in The Primitive, “A fighter fights and a writer writes.” Certainly, in his life, he’d been scraping since he was a teenager. Himes came from a troubled family of educators who moved from Jefferson City, Missouri to Cleveland when Chester was eight. Though he came from a family of strivers, his dark-skinned father was unemployed and emasculated by his much lighter wife.

Rebelling against his parents constant arguing, Himes hung out on the wrong side of the tracks, where he gambled, chased women and listened to the blues. Although Himes graduated from East High School and was accepted into the University of Ohio, he was soon suspended for taking some students to a whorehouse where a fight broke out and word got back to the dean. According to James Lundquist’s monograph Chester Himes, he returned to his family in Cleveland where he was soon playing in illegal poker games, working in a hooker hotel, paling around with Capone cronies, passing bad checks and stealing cars. Himes finally went down for jewel theft and was originally sentenced to twenty years.

It was while in the slam that Himes began to write. With a Remington typewriter in his cell along with Black Mask magazines, surprisingly, he also began to sell his short fiction. In the beginning his autobiographical stories, most reprinted in The Collected Stories of Chester Himes (2000), were published in Negro publications the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier and Abbott’s Monthly. “The Chicago black journal that also published in the 1930s Langston Hughes and the first work by Richard Wright,” Robert B. Stepto wrote in 2017. “Himes was writing himself into the company of those writers, even before he left prison and met them.”

In 1934, Himes managed to cross the editorial color line that existed at the glossies when he began contributing to Esquire with the stories “Trouble in the Stir” and “To What Red Hell.” The latter story was based on a prison fire that killed over three hundred men. Esquire editor and co-founder Arnold Gingrich bought those pieces for fifty dollars. Keeping it gangsta, Himes published those two stories under his prison number 59623.

After his release in 1936, Himes continued to write while also working a series of jobs, got married to a woman named Jean (“The most beautiful brownskin girl I had ever seen,” he once described her) and relocated to Los Angeles where he completed his critically acclaimed debut novel If He Hollers Let Him Go. Published by Doubleday in 1945, the inner flap cover copy compared Himes “hard hitting prose style” to James M. Cain and, according to Los Angeles Review of Books critic Nathan Jefferson, although there were no detectives, the book shared a noir sensibility with Himes’ later novels. If He Hollers Let Him Go told the brutal tale of racism in Los Angeles as experienced by the weary Bob Jones, a leadsman at a Los Angeles shipyard who was trying to maneuver through a barbed wired life during the of World War II.

Although Jones wasn’t on the bomb dropped front lines in some foreign land, he still fought every day as he tried to keep from going tick-tick-boom on the next person who called him a nigger or boy while looking down on him. In Himes’ fiction, racist slights and outright insults are always lurking, ready to pounce like a boogeyman behind the next dark corner. There was also an existential strain shimmering through the book that comes, as critic Hilton Als wrote in the forward to the 2002 edition, “closer to Camus’s The Stranger than to Native Son or Invisible Man…a portrait of race as an economic and psychosexual prison—or padded cell.”

Fast forward to the down and damn near out early days in Europe, and, under the guidance of Duhamel, Himes published the bullet ridden For Love of Imabelle aka A Rage in Harlem. At first, Himes thought of the work as “demeaning,” and “hoped to soon to get back to serious writing.” Published in 1957 and set in Harlem, For Love of Imabelle featured unpleasant NYPD detectives Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones. Initially published in France, where it was quite popular, and the novel was sold in the states where it created a small sensation. “Himes did for Harlem what Bunuel did for Spain and Fellini for Italy,” says author Robert Fleming, who cites Himes as an influence, “by giving a full-tilt reality exaggerated to almost cartoonish grimness and exotica.”

Although Himes wasn’t the first African-American detective writer, an honor that goes to Harlem Renaissance author Rudolph Fisher’s second novel The Conjure Man Dies: A Mystery Tale of Dark Harlem (1932), he was the best known until Walter Mosley’s Devil in a Blue Dress in 1990. Unlike Baldwin, Himes never lived in Harlem, but that didn’t stop him from using the chocolate city within New York City as the backdrop. He had visited there often, and in the winter of 1955, while on an extended stay in the city, he and Barbadian novelist George Lamming made Harlem their playground.

Biographer Lawrence P. Jackson, whose book Chester B. Himes was awarded an Edgar Award in 2018, says that Harlem experience “awakened in Himes another view of the black heart of the city.” Himes began returning to Harlem “viewing with fascination the low life, the gambler, the pimps and the prostitutes and gathering material for a kind of fiction he did not yet know he was going to write.” In Harlem, he also discovered “that I still liked black people and felt exceptionally good among them, warm and happy. I dug the brothers’ gallows humor and was turned on by the black chicks. I felt at home and I could have stayed there for ever if I didn’t have to go out into the white world to earn my living.”

Himes’ Harlem was also purposely surreal and absurd. In fact, absurd was also how Himes defined his own existence. “Realism and absurdity are so similar in the lives of American blacks one cannot tell the difference,” he wrote…Returning to Paris in early 1956 to begin writing his first Harlem novel, two months later he delivered For Love of Imabelle. However, while Harlem would become as important as the detectives and criminals who roamed the landscape throughout Himes’ crime books, the blocks and boulevards in those books were not supposed to reflect reality. With prose that was vivid as a Romare Bearden collage, Himes’ Harlem was also purposely surreal and absurd. In fact, absurd was also how Himes defined his own existence. “Realism and absurdity are so similar in the lives of American blacks one cannot tell the difference,” he wrote in the second volume of his autobiography was titled My Life of Absurdity (1976), a book that greatly inspired Negrophobia author Darius James when he left America for Berlin twenty years ago.

“I could identify with Himes’ experience as I too was disappointed with my homeland and disheartened that the reception of my writing didn’t translate into genuine financial support,” James says. “The life he described helped to clarify who I was as a man and an artist. Ultimately, his autobiography of his productive years in exile gave me the understanding and strength I needed to do the work ahead of me.”

Crime writer Kenji Jasper, whose fifth novel Nostrand Ave was released last year, cites Himes first autobiography The Quality of Hurt as a favorite. “I was super impressed by the fact that he gave no fucks about doing what he wanted to do,” Jasper says. “He taught me that a writer’s life is about constant reinvention and constantly hustling. All of this helped me to welcome a life writing about the underworld and love doing it.

When Chester Himes moved away from protest as his theme, it “forced Himes…to mask his rage as humor, to transfer his focus from himself to the diverse,” writer Luc Sante pointed out in his introduction to a 2011 Rage reissue. That book became the first written by a Black writer to win the prestigious Grand Prix de Littérature Policière. “Moreover, they featured the first significant inroads by an African American author into the overwhelmingly white world of hardboiled fiction,” author Megan Abbott explained it in her book of essays The Street Was Mine.

The following year, the second book in the series, The Real Cool Killers, was published. By the time he finished the third book The Crazy Kill, the notoriously temperamental writer was already becoming bored with his detectives. At the suggestion of Duhamel, for his next novel Himes set out to write a different kind of Harlem narrative, one that was more serious, darker in vision and didn’t include Coffin and Grave Digger.

***

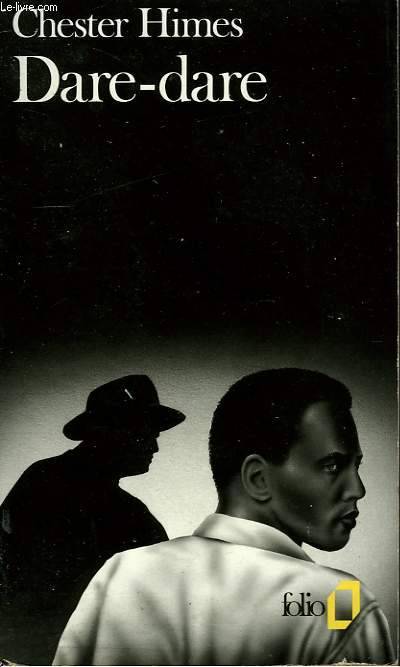

First published sixty years ago in France, Run Man Run (currently out-of-print, but still widely available) merged Himes’ pulp and literary sides to create a haunting book that packs a hellish punch. Published under the title Dare-dare in France, the book wasn’t translated and reprinted in America until 1966, at the height of the civil rights movement and the same year as the Watts Riot. A scary tale of a drunken white cop named Matt Walker who slays two automat workers in the middle of the night after drunkenly accusing them of stealing his car, the book is not as well known as the other Harlem books. The rest of the story involves Walker’s cat and mouse chase of the third worker, Jimmy, as he pursues him over the course of a few winter weeks after Christmas.

As Walker viciously trails Jimmy through midtown basements and across Harlem boulevards, no one wants to believe the Black man that the cop was out for blood. Hell, even Jimmy’s girlfriend Linda Lou has her doubts and the authorities show their position when they briefly put him in Bellevue, the city’s most infamous mental hospital where he is put into a straight jacket and held for observation.

“Jimmy’s story seems farfetched even to those close to him,” writer Gary Phillips, author and editor of numerous crime books and the forthcoming graphic novel The Be-Bop Barbarians, says. “In the days before video cameras and camera phones, it was just your word against the police. We can start with the Rodney King beating in 1991, because it was only because of the video footage that those policemen were taken to trial. Run Man Run was grounded in a reality that still exists. I’m surprised no one has made a movie from it.” In 1972, Himes attempted to write a screenplay from the novel, but, due to illness, he never finished.

The book’s plot was formulated from the days of Himes working as a night porter at the Horn & Hardart automat on 37th and Fifth Avenue in 1955, and his own experiences of dealing with a drunken policeman on the premises. Indeed, not much has changed in some folks minds when it comes to race. As writer Ayana Mathis pointed out in her 2018 New York Times essay about Black male writers, “Slavery-era fixations and caricatures still titillate and terrify: Black men are a threat to order and the status quo, physically imposing and possessed of exaggerated sexual ability. Therefore, they must be contained.” Or killed.

Run Man Run came to my attention in 1990, the same time I was knee deep in David Goodis and Jim Thompson reissues. Back then, I thought of the book as a simply another thrill ride down those mean streets. The psycho policeman of Himes’ book was like the college educated/city dwelling cousin of Lou Ford, the murderous deputy sheriff in Thompson’s scary The Killer Inside Me. However, re-reading Run Man Run recently, the book carried more weight and it was impossible to not think of Rodney King, Oscar Grant, Eric Garner, Botham Shem Jean and countless other Black men who have been brutalized or killed by white police officers.

Himes was treated as a genius in Europe, critically lauded by Jean Giono, who wrote, “I give you all of Hemingway, Dos Passos and Fitzgerald for this Chester Himes.” Still, in America he was just another paperback crime writer and sometimes the gaudiness of the covers were a reflection of that insolence. The original Dell paperback version of Run Man Run was adorned with a picture of a seductive woman and cover copy that read, “Lush sex and stark violence, colored black and served up raw.”

Himes was livid and wrote a letter to Dell executive Helen Honig Meyer proclaiming that the cover, “constitutes a false and derogatory commentary on my objectives and descriptive copy ignore the entire point and theme of my story.” In conclusion, Himes tossed a textual Molotov cocktail when he wrote, “If it is necessary to put this type of cover…on this book in order to sell it to the American people, the American people are really and truly sick.”

Author Scott Adlerberg, who wrote about Chester Himes for the forthcoming Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980, says, “With Run Man Run, Himes was able to switch from the detective form to the bad cop novel that was both realistic and creepy. But, whereas the Harlem of his detective novels was often depicted as off-kilter, hyper-landscape, Run was written as social realism that was thrilling and dramatic, but with none of the satire found in the other books. Although Himes seemed to live a good life, he never let go of his anger.”

The sickness of racism runs through the book, which was written at a time when the south was often portrayed as the hotbed of racial discrimination while eastern cities shook its collective heads in shame and acted as though they weren’t sharing the same experiences.The sickness of racism runs through the book, which was written at a time when the south was often portrayed as the hotbed of racial discrimination while eastern cities shook its collective heads in shame and acted as though they weren’t sharing the same experiences. Still, you only had to visit the big apple to see that the subpar treatment of Blacks in Harlem in the 1950s wasn’t that different from their southern relations. Although there were no official Jim Crow laws on the books, when it came to housing, education and jobs, “Negro” New Yorkers knew that the same Mason-Dixon Line prejudice was in full effect.

With Jimmy, a recent graduate of North Carolina College who moved to New York to attend Columbia University Law School, he was new to the race deception of the big town. Even as Walker stalked him, in one chilling scene standing across the street from his apartment building staring up at Jimmy’s window, the young man reasoned that all of the madness he was experiencing was based in something deeper than race hate. “White men had murdered those civil rights worker in Mississippi, bludgeoned them into pieces. But, this was New York City.” Nevertheless, as he saw the crazy cop standing near the doorway of his building on 149th and Broadway, he reasoned, “White cops were always shooting some Negro in Harlem. This was a violent city, these were violent people.”

For me, the only weakness of Run Man Run can be found in Himes’ women characters, especially Jimmy’s jazz singer girlfriend Linda Lou who, in trying to be helpful, comes across as misguided and naive. While Himes protested that he had “presented her as a normal American woman with morals and passions similar to most American women,” I didn’t understand why Linda thought that making love to Walker would keep him from killing her man. Himes, like many other noir writers of his generation, could be misogynistic, creating women characters that were simply disposable dames. Walker’s European girlfriend Eva, who the cop rapes, beats and threatens with deportation, is another example of that trait.

While Run Man Run is one of Chester Himes’ best books, it is also one of his least known, though Megan Abbott’s sixteen thousand word essay “The Strict Domain of Whitey: Chester Himes’s Coup” gave the novel a close read while also giving Himes props for elevating noir fiction to the next level. “He has created a fictional structure that defies social realities as he sees them and thereby comments on the oppressive absurdity of black life in a racist America.”

Author Robert Fleming says, “In Run Man Run the author’s handling of race, corruption, prejudice and the mind of a psychotic cop keeps the reader on edge. Himes is at his best here. It was the right book at the right time.” Fifty-three years after its American publication that time is still now.