Living on 151st Street between Broadway and Riverside Drive in 1973, there were more than a few shops in the community where chattering kids bought all types of cavity inducing treats. My favorite spot was Jesus’ Candy Store, where the Hispanic owner and his wife watched over us kids as though they were our surrogate parents. Jesus’ place overflowed with toys, school supplies, Spalding rubber balls, comic books, chips for Skully tops and, of course, candy. However, Jesus didn’t unlock his door until the afternoon, leaving the morning trade wide open.

In the summer of 1973 a new shop opened on Broadway owned and run by an overweight brother man named Jesse Powell. His store was minimalistic in comparison to Jesus’, but he opened at 7 AM. Weighing about 300 pounds, Jesse sat on a strong stool behind the counter.

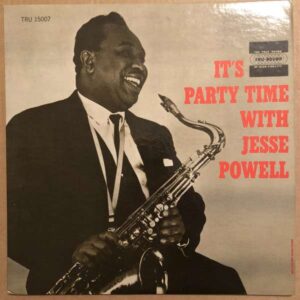

Nailed to the wall behind him was an album cover, but many years passed before I realized that it was the cover to his album It’s Party Time With Jesse Powell (1962). In the photo he wore a suit, his hair conked and sharp as a tack. Jesse had once been semi-famous saxophone player who had toured with Count Basie and Dizzy Gillespie before giving it up to open a sweet shop on Sugar Hill.

From where he sat, Jesse could see downtown traffic moving steadily as kids played. Sometimes Jesse’s wife Maxine was in the store helping. She was a tall, friendly woman with long blonde hair who had hippy vibes. Jesse was obviously years older than Maxine, and the couple had a son and a daughter. My homeboy and former next-door neighbor Darryl Lawson recalls Jesse’s car was usually parked in front of the store. “When he got in that Cadillac, it just leaned over to the side,” Lawson laughed.

In the mornings, on my way to St. Catherine’s grammar school three blocks away, the store would be packed with school children stocking up on sweets that had to last the day. Rowdy kids from my 4th grade class would be buying Now & Later, Mary Jane, Charms Blow Pops, Fun Dips and other brands that they buried in their book bags to sneak eat during class. A few friends were into sports, and they bought stacks of baseball, football and basketball cards that were produced by the Topps Company out of Brooklyn.

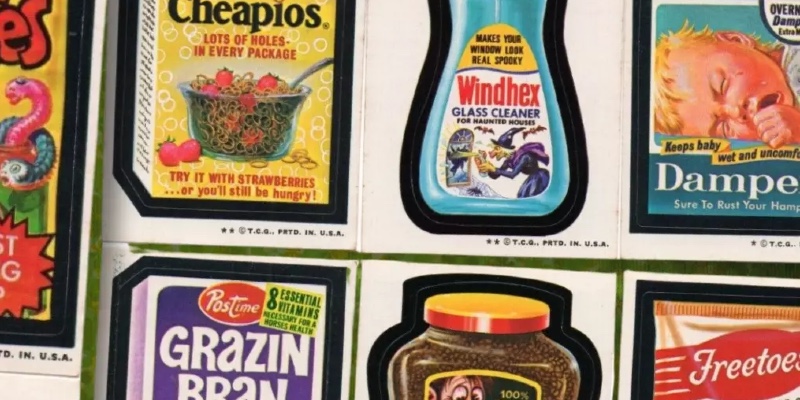

For those too young to remember, Wacky Packages was a back in the day craze – irreverent stickers mocking commercial products in the same way MAD magazine parodied popular culture. The Wacky parodies included Weakies Cereal (Breakfast of Chumps), Liptorn Soup, Jail-O (Sing-Sing’s Favorite Desert) and many others. The creator of Wacky Packages was underground comic artist and illustrator Art Spiegelman, who introduced them to the company in 1967.

“It was printed cardboard with a gummed back,” artist Jay Lynch, who too contributed to the product, wrote in a 2016 issue of Comic Book Creator. “The kids would punch out the product images and lick the back to stick’em on stuff. But the Wacky Packs didn’t really take off big until the early ‘70s, when Topps’ began printing them on peel-back-pressure-sensitized sticker paper.”

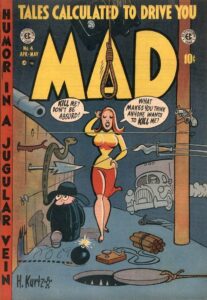

Spiegelman came of age in the EC era when publisher William Gaines launched the infamous humor comic. Almost two decades later Spiegelman made history as the first comic book artist to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize for the graphic novel Maus in 1992. He also edited the cutting edge graphic arts magazine RAW with his wife Françoise Mouly.

“As a child, Spiegelman was obsessed with MAD magazine and its founding editor, cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman,” Arie Kaplan wrote in “MAD Maus,” an essay in the Jewish Review of Books. “It is easy to look at (Harvey) Kurtzman’s early MAD and see cheap, disposable children’s entertainment. But MAD was the holy grail of subversive kid lit for the generation that came of age during the 1950s and 1960s.” Artists Jack Davis and Wally Wood, both former EC cartoonists, also contributed to Wacky Packages.

Later, Kaplan quoted Spiegelman’s memoir essay in MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic: “My Topps Bubblegum job consisted of feeding back my MAD lessons to another generation in the form of Wacky Packages… sometimes illustrated by the same artists—my childhood idols!—that Kurtzman collaborated with at MAD.”

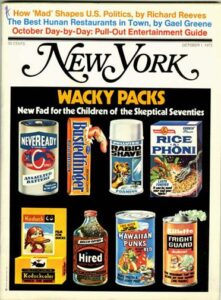

Selling for five-cents the Wacky Packys (as we called them above 145th Street) soon became a city-wide sensation that included news reports and a cover story in New York magazine, a goofy tongue-in-cheek feature that was as informative as it was condescending. Wacky Packs: New Fad for the Children of the Skeptical Seventies was published on October 1, 1973 and basically attributed the stickers’ success to cynical children living through the age of Watergate hearings and hating everything their parents loved (and respected).

Personally I liked them simply because they were funny as hell. Released the same year as the offbeat DC comic horror Plop!, which was also inspired by MAD, sick humor was in and kids loved it.

According to Jay Lynch’s article “The Wacky Pack Men,” they worked out of an office located in the Brooklyn Navy Yards with a team that consisted of future underground and strip artist Bill Griffith (Zippy the Pinhead), writer Stan Hart (Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In) and illustrator Norman Saunders, who did the final paintings from Lynch and Spiegelman’s layouts. Saunders was a respected artist who had painted hundreds of pulp magazine and paperback covers. He’d also been the artist been Topps’ popular Mars Attack in 1960.

*

One Saturday afternoon my stepfather Carlos stopped by the apartment to drop off a color TV for our living-room. My brother and I got him to agree to take us to the store for candy. When we walked into Jesse’s shop, he and Daddy glanced at one another and erupted in a joyful noise. The two men screamed each other’s name and shook hands.

“What you doing over this way Carl?”

Daddy laughed. “My wife lives around the corner. Just came over here to get the kids some candy.”

“These your boys?” Jesse asked.

“Sure are,” Daddy replied. Though he’d been in America for decades, his Puerto Rican accent was thicker than Guava slices. “Show Mr. Jesse what you want.” Me and little bro Perky both pointed to the Wacky red box inside the glass counter. Daddy bought us five each, which made us kid rich, our pockets bulging with stickers.

After Jesse found out that he knew my father, he was a bit nicer to me and baby brother, sliding us an extra Wacky Package whenever we bought a few. However, two incidents occurred that soon put an end to my visits to Jesse’s.

The first was his purchase of a mean Doberman Pinscher that he kept behind the counter. Perhaps someone tried to rob the store or the dog was supposed to be a deterrent for criminals, but that canine scared me to death. The other happened at St. Catherine where a crew of upper classmen went crazy and stuck Wacky Package stickers on their desks, on the walls and the lunchroom tables. I’m sure the school’s custodian Mr. Cafiero must’ve blown his top which led to Principal Sister Mary Riley banning the product completely. “Anyone seen with these Packys will be suspended for three days,” she said.

Evidently the Wacky fad faded, and though the Topps Company continued to make the product for decades, most of kids I knew stopped buying them. These days there exists a large collectors market with fans selling rolls of stickers and unopened packages online.