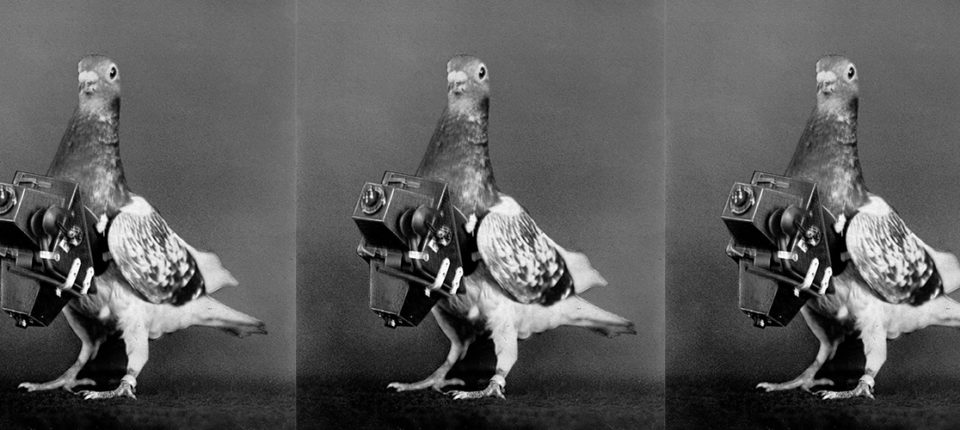

Pigeons possess all the qualities of a stellar secret agent. They’re hiding in plain sight: unobtrusive, unassuming. Bundle them into the back of a van—or a plane—or a mobile pigeon loft, drive them hundreds of miles in any direction, and they’ll unreservedly set out into the fray, risking life and limb to fly straight back home with the messages entrusted to them. In short, they are as well-equipped for covert operations as James Bond, but with fewer destructive tendencies. (Their messes can be dispatched with a good soapy brush.) They’re also not nearly as free with their affections, preferring instead to mate for life.

But Bond is a fiction; pigeons are the real deal. A great many of these extraordinary birds have performed critical intelligence work on His Majesty’s Secret Service. The “His” refers to HRH George VI, King of the British Commonwealth for the duration of World War II. Seventy-five years on since the official end of the war, pigeons have settled into civilian life rather unappreciated. Memories are short, at times intentionally, when the pain of remembrance is too great. But in those dark, desperate years of war, pigeons were heroes. And the world knew it.

The Dickin Medal was instituted in 1943 to recognize the heroic feats of animals serving in wartime with the British Armed Forces and the Civil Defence Services. A bronze medal, marked with the words, “For Gallantry. We also serve,” the Dickin is widely accepted as the equivalent of the Victoria Cross. Fifty-four of these medals were bestowed for extraordinary efforts during the war; thirty-two of them went to pigeons.

“For delivering the first message from the Normandy Beaches…”

“For delivering an SOS from a ditched Air Crew close to the enemy coast…”

“For bringing 38 microphotographs across the North Sea in good time although injured…”

“Brought a message which arrived just in time to save the lives of at least 100 Allied soldiers from being bombed by their own planes.”

Even with the technological advances in use during World War II, pigeons were clearly not yet obsolete. With their innate ability to home when released in far-off and unfamiliar places, pigeons have been used as messengers throughout history. With their assistance, Genghis Khan kept tabs on his territories, Greeks learned of Olympic victories, and Parisians communicated from a city under siege during the Franco-Prussian War. For some, the birds were bonafide business partners.

Keen to capitalize on the outcome of the Battle of Waterloo, banking magnate Nathan Rothschild kept carrier pigeons at the ready to dispatch news of victory or defeat. His machinations earned him a two day head start on the news of Napoleon’s defeat, prompting a slew of favorable trades on the British stock exchange. Reuters news service employed pigeons in the mid-nineteenth century to bridge the gap in the telegraph lines linking Paris to Germany, thereby bolstering the company’s reputation for fast and accurate news.

But by the 1850s, pigeons that had been kept by merchant or news agencies were being supplanted by the telegraph. Consequently, the birds were sold to individuals, giving rise to the burgeoning sport of pigeon racing, which, unlike horseracing, was not the exclusive domain of the wealthy. Anyone could own a pigeon or two—or twenty—and breed and train them for racing. So for miners, weavers, and shop assistants, whose everyday lives were tedious and rather dismal, the pigeons were a breath of fresh air. The unassuming little birds managed to tick all sorts of boxes: pet, hobby, social activity, and even supplemental income. Even the royal family couldn’t resist their allure. After receiving a gift of pigeons from King Leopold II of Belgium in 1886, the future Edward VII parlayed them into a royal loft that, to this day, continues to produce champion racers.

Pigeons were used with considerable success in the Great War on both sides of the conflict, but at the end of the war, the British disbanded their pigeon service. Consequently, in 1937, when Germany began to show signs of warmongering, William Osman, editor of the Racing Pigeon and son of WWI pigeoneer Alfred Osman, felt compelled to appeal to the Secretary of the Committee on Imperial Defence to reinstate the pigeon service. The voluntary National Pigeon Service may have been starting from scratch, but there were 70,000 pigeon lofts across Britain, and the NPS appealed to all fanciers.

A loft was expected to supply twenty birds a month to the service of the British military—and pigeon feed was reserved for those lofts that signed up. Long and short distance pigeon racing may have been put on hold indefinitely, but the racers were nonetheless expected to do their bit. Only the conditions had changed. The birds would still be expected to set a breakneck pace, but they’d face all-season weather over the English Channel, dry desert conditions in Northern Africa, and humid mountain ranges in Burma. They’d need to brave natural predators, sniper and artillery fire, the wreckage of downed aircraft, and German-trained falcons. They’d be expected to fly at night and over water—both conditions that pigeons naturally avoid—and do it all under the radar, as it were.

Racing pigeons were uniquely equipped for the tasks the war office set them. A pigeon’s wings are 20-30% of its body weight and can beat three times per second. With a tremendously efficient respiratory system, comprised of smallish lungs and eleven air sacs, and a heart that beats six hundred times per minute, the birds are able to maintain an average speed of 60 mph over hundreds of miles. A desire for home drives them, and it is thought that they use a combination of visual, auricular, and olfactory cues to find their way. Resilient, adaptable, and dependable, they were often the last hope of pilots, soldiers, and agents when wireless communication was impossible.

Despite their ability to fly under the radar, pigeons were not, unfortunately, a secret weapon. Germany had, in fact, maintained its pigeon service during the interwar years, and was arguably better equipped to capitalize on the birds’ prowess and versatility even as Hitler began his ruthless march across Europe. The military, Gestapo, and the Schutzstaffel (SS) were supplied with birds bred and trained by the state-run German National Pigeon Service, whose president was longtime fancier and head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler. In addition, there were five government-run falcon centers, tasked to intercept Allied pigeons flying home across the Channel. Pigeons were part of the German advance team, laying the groundwork for an invasion of Britain. Carried or dropped into enemy territory, they were sent home by German agents with details of British defenses and Fifth Columnist support. The Nazis even went so far as to confiscate the pigeons in every country they occupied, eager to prevent their use by anyone engaged in covert resistance. The birds were tremendously versatile, and both the Allied and the Axis powers brainstormed methods to make clever use of them, but their greatest success lay in winging messages home.

Over the course of World War II, pigeons carried countless messages, microphotographs, maps, and other documents. In so doing, they managed to save an impressive number of lives. But despite the astounding feats that made them seem almost untouchable, the reality was quite the opposite. They were, quite simply, warm, living, breathing symbols of hope and home. Much like their human counterparts, in combat and on the home front, they did their bit selflessly and courageously, and they deserve to be celebrated and remembered. But don’t count them out just yet. In the current climate of technological dependence and modern cyber warfare, in which communication systems can be hacked or jammed, a pigeon redux could be a very cagey, if not entirely secret, weapon.

***