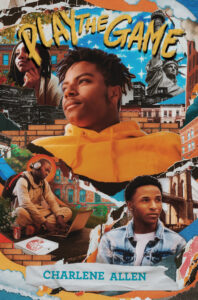

If I had to choose a favorite lineage within crime fiction, I’d pick one that includes Tony Hillerman, Barbara Neely, and Tiffany D. Jackson. Though their styles differ dramatically, these writers deliver satisfying stories whose marginalized protagonists question traditional responses to crime. Their books offer insight into survivors’ healing needs beyond exposing “the bad guy.” And they highlight the community’s role in responding to crime where institutions fall short. My debut novel, Play the Game, follows in their footsteps.

Play the Game, a YA mystery, opens with the announcement that Phillip Singer, known to the public for killing a Black boy named Ed Hennessey, has just been found dead in the same spot where he killed Ed. When the police arrest Jack, another young Black man, our reluctant sleuth, VZ Brown, is spurred into action. A friend to both Ed and Jack, VZ decides the only way to save Jack is to find out for himself who killed Singer. He gets unexpected help in the form of a video game, designed by Ed, which seems to give him clues to Singer’s murder. And as he moves deeper into the world of policing and detective work, he uncovers uncomfortable truths about what the system can and can’t provide.

Years of working with courts and with survivors has taught me that traditional responses to crime can be deeply unsatisfying for all involved. Once a trial or plea bargain is over, most survivors are left with questions and feelings that have no place to go. And, rather than increase safety, the violence prisons perpetrate can increase violence in our streets. So, in Play the Game, I wanted VZ to explore other options, similar to Tony Hillerman’s protagonist Jim Chee.

Chee works as a police officer. But his Navajo sensibilities are so antithetical to western notions of justice that he is able to see past his duties to find responses that bring safety, accountability and healing in forms that best suit each situation. Like VZ, Chee loves the puzzle, the investigation, but he understands that what happens in the end must depend on the needs of the people and communities involved, not the ever-turning wheels of the legal system.

In Sacred Clowns, Hillerman’s eleventh book, Chee sets out to find the hit-and-run driver who killed a man. He discovers that the driver has taken responsibility for the crime and begun sending money to the victim’s family on a monthly basis. The driver is also the primary caretaker of his grandson, who has fetal alcohol syndrome. Understanding that the driver himself, his grandson, and the victim’s family will all suffer if he’s sent to prison, Chee takes matters into his own hands and helps the driver avoid arrest – the best solution to restore the community to all it has lost.

In Play the Game, as VZ pursues clues to find Singer’s killer, he finds healing in his efforts to help his friends. But VZ isn’t the only one who’s been hurt by the two murders that have taken place. The entire community, harmed by senseless violence against young Black men, also needs to heal. As does the family and community that Singer left behind. To address that, I wanted to explore a deeper critique of the systems themselves and highlight options for community action where systems fail. I wanted to dig into the complexity of where justice meets healing.

Barbara Neely does just that in her pioneering mystery series. Book one, Blanche on the Lam, introduces us to Blanche, a curious and industrious Black woman who works as a domestic. She’s just been sentenced to jail for bouncing a check because her employers paid her late. Succumbing to a panic attack, she runs for it … and ends up entangled in the family drama of her new employers, where she figures out who has committed murder in order to claim the family fortune. When the crime is revealed, the “perp” is sent away to “some place private,” to address their mental health issues in relative comfort. The story starts with the system injustice of sentencing Blanche for the crime of being poor and ends with the unfairness of buying one’s way out of harsh punishment. Throughout the novel, it’s Blanche as a caring community member who solves the crime and takes steps to ensure that those who are harmed will be safe and have opportunities to heal.

Similarly, Tiffany Jackson’s YA mystery Monday’s Not Coming examines the shortcomings of our child protective systems: our schools, in their role of guardians of children’s safety and well-being, as well as our state and city systems. The story opens with, “This is the story of how my best friend disappeared. How nobody noticed she was gone except me. And how nobody cared until they found her . . . one year later.” Although the book deals with issues of parental abuse, Jackson’s real focus is on the community’s responsibility – teachers, friends, guidance counselors, and other parents who must look out for our children, and demand that our systems do their jobs.

As in Monday’s Not Coming, young people in Play the Game also see the system’s flaws with clear eyes. But as VZ begins to understand what happened to Singer, he realizes that not all systemic problems can be repaired. Together with his friends and some supportive adults, he explores what it means for people to act on their own to hold one another accountable and help each other heal. After all, as one character puts it, “What are systems, beside the people who make them up.”

Stories like those of Hillerman, Neely, and Jackson offer all the delicious sleuthing that crime fiction is known for, as well as critiques of and alternatives to system-based responses that have harmed those they should serve. Their work contributes to the larger national conversation about violence, punishment, safety, and healing. I hope Play the Game continues in their tradition.

***