It’s never been cooler to be a ‘weird girl’. Pop sensation Chappell Roan says her dream date is a ‘weird art girl’. Last year, the surrealist film Poor Things featured a wild young woman with a foetus brain implant to critical and commercial success, and in January, Lucy Rose’s novel The Lamb took lady-cannibals mainstream becoming a bestseller.

As readers increasingly reach for books about eccentric, if not strange, convention-defying young women, female-led horror fiction sales boom. The Bookseller reports an upward trend in horror with the value of the category in the first quarter of 2025, up over a third against the same period in 2024, and now a new sub-genre is being touted: ‘weird girl’ horror.

‘Weird girl’ horror purportedly falls out of ‘femgore’, which A K Blakemore described in The Guardian last year as novels about young women ‘who stalk, slash, bludgeon, infect, slice, dismember and cannibalise.’ Don’t panic, it’s probably all a metaphor. Historically, young women in horror and thrillers were the victim or the perpetrator. So, either perfect girl Sidney in Scream, or the Femme Fatale—a la seductive, sociopathic Amy in Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl—and the more traditional Monstrous Woman—think fairy tale tropes of older witches and evil stepmothers, including a religious sub-category of demon-possessed girls like Marjorie in Paul Tremblay’s A Headful of Ghosts. In some senses she may be a victim, but ‘weird girl’ is socially clueless, and unlikely to seduce. However, despite being young, she’s nailing the taboo-embracing of Monstrous Woman.

Weird girl sounds not dissimilar to Manic Pixie Dream Girl, who skipped into the noughties eccentrically, hyperactively, and emotionally unstable-y to teach self-absorbed boys more about themselves and what they want. MPDG was personality fetishized. However, the idea of her loomed larger than the reality of representation itself on screen and page, as many critics pointed out. Even the coiner of the term ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’, Nathan Rabin, disowned it as being too reductive in his 2014 renunciation in Salon entitled ‘I’m sorry for coining the phrase “Manic Pixie Dream Girl”.’

At first, ‘weird girl’ might seem like MPDG, although without the whimsical smile and vintage wardrobe. Or even a reaction to the MPDG trope, turning eccentric charm and playfulness from attractive to grotesque. However, to frame ‘weird girl’ as a reaction to the trope, or even a subversion of it, still focalises male perspectives and leaves us unable to address her own unique pathologies. (This is exactly what critics of MPDG also said.)

But ‘weird girl’ isn’t a totally new literary phenomenon. Inflections of supernatural and psychological tension have long served young female protagonists exploring social proscriptions. Like the atmospheric locations she haunts, ‘weird girl’ is remote and disordered. She is vulnerable, but threatening: full of emotion or cauterized, often both at once. If you really understand her, she’s probably not weird.

‘Weird girl’ takes the strangest path through oppressive situations. Absorbed by Kylie Whitehead sees the protagonist literally absorb her boyfriend and manifest his personality to interrogate the dangers of romantic co-dependency. Deliver Me by Elle Nash features a young woman so obsessed with the social pressure to have a child that she is determined to give birth, whether or not she’s actually pregnant, to a disturbing, bloody conclusion. In her recent novel Carrion Crow, Heather Parry’s protagonist Marguerite responds to her mother incarcerating her in preparation for a traditional marriage, by memorising Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, entering a parasocial relationship with a bird and indulging in demented pica.

In fact, ‘weird girl’ is a gothic legacy. Before Irina exploited young men for her art in Boy Parts by Eliza Clark, there was Estella, trained into dissociative misandry by her bitter mother-figure in Great Expectations (Dickens). In Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, is the governess—she never has a name—seeing ghosts, or psychotically anxious? Young women have been socially alienated for hundreds of years, so female-led horror is probably a sub-genre of the ‘weird girl’ canon, not the other way around.

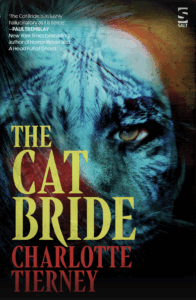

Books about ‘weird girl’ have enduring appeal because she circles perennial questions about who she understands she is, versus who she’s told she is. Her story is her failing attempt to reconcile the two. My own ‘weird girl’ book, The Cat Bride, is set in the nineties. Then, as now, the nubile young woman sat in the Venn diagram between societal expectations and self-actualisation, in psychological chaos. The protagonist, Lowdy, is trapped by promises of traditional fairy-tales on one side and burgeoning lad culture on the other. I didn’t intend to write a ‘weird girl’, but loud metaphors can be an effective way to explore otherwise quiet, insidious injustices. In Lowdy’s case, she may, or may not, start shapeshifting into a massive, predatory cat.

The ‘weird girl’ seems so overwhelmingly evergreen, perhaps no one’s writing ‘weird girls’ at all, they’re just writing ‘girls’. Heather Parry told me, “I never consciously set out to write ‘weird girls’; I write women at odds with the expectations of their gender, their society, their physicality, and other people’s attempts to control them. This chimes with so many of us, which is why I think these characters are popular. I do note, though, that when male authors write characters at odds with masculinity or society, they’re never softened down into a ‘weird boys’ trend.” If a young woman behaving contrary to traditional femininity is by definition ‘weird’, can this be considered a progressive feminist trope?

On the other hand, there’s an irony to the reductive moniker ‘weird girl’ and a subversive black humour coursing through most ‘weird girl’ stories. Perhaps bleak characters with unconventional solutions to disturbing situations is what we need in the strange end-of-days we’re living through. With improved attention to inclusivity, society now validates atypical interests (ant-farming, say) and behaviours (hating parties) celebrating them widely through the bizarre intimacy of social media, so we are both weirder and more familiar to each other than ever before. ‘Weird girl’ fiction contains the same dichotomy—the girl is weird, but what she revolts against is ubiquitous. Red Newsom, bookseller at Blackwell’s Manchester says, ‘The current success of Weird Girl Fiction as a genre has created a safe space for readers to explore desire, empowerment and resistance away from the male gaze. Perhaps when we say “unhinged”, what we mean is “unrestrained”.’

It looks like weird is the new (and old) normal. Let’s get T-shirts made.

______________________________