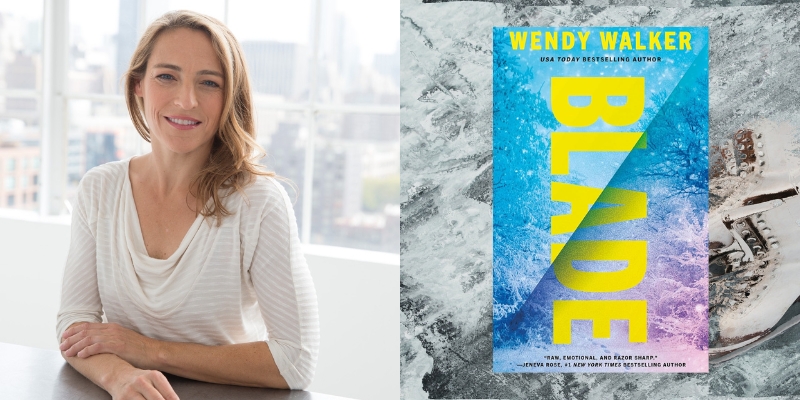

Writing, like figure skating, is as much a test of emotional stamina as it is an expression of artistry—which is something Wendy Walker knows better than most.

Renowned for her bestselling psychological thrillers, Walker’s newest standalone novel of suspense, Blade (February 1, 2026, from Thomas & Mercer), draws on a highly personal experience: her upbringing as a competitive figure skating. As a teenager, Walker left the comforts of home to spend three years under the tutelage of famed Olympic coach Carlo Fassi at an elite training facility in Colorado Springs.

As heady a time as it was, it was also harrowing; indeed, she felt unmoored without the grounding force of family and friends. The resultant turmoil of that time deeply informs the emotional undertones of Blade.

Ana Robbins left the world of competitive figure skating at sixteen years old, after watching it destroy her friends and her own sense of self. Fourteen years later, she is a highly regarded attorney specializing in the defense of minors (echoing the author’s previous career in family law).

It’s in this capacity that she returns to her former home in the Colorado mountains (known as “The Palace”), where young Grace Montgomery has fallen under suspicion of killing her coach, Emile Dresíer. Not only is Grace the daughter of one of Ana’s friends, but Emile was one of her coaches when she trained there. Consequently, Ana has unique insight into the nature and nuances of life at The Palace.

With investigators closing in on tight-lipped, seemingly aggressive Grace as their culprit, Ana must confront the ghosts of her youth if she has any hope of unraveling the truth—and not simply of the night Emile died but how her own experiences may have played into the perpetuation of a generations-spanning cycle of abuse.

After all, trauma comes down like snow on treetops, obscuring clarity under the façade of familiarity. As a blizzard rages outside, it’s the storm brewing within her that may just prove to be Ana’s salvation as she comes to terms with how history has led her here.

Now, Wendy Walker discusses the fine lines of crossing fiction and fact for the purposes of storytelling.

*

John B. Valeri: Blade is a great example of writing what you know to capture an essence of truth rather than the literal truth. Tell us how your own background and experiences in competitive figure skating informed the emotionality and physicality of the characters we meet and their circumstances. Did you find that revisiting your own past, albeit through the lens of fiction, provided a sense of clarity or catharsis?

Wendy Walker: When I was thirteen years old, I moved away from home to train at an elite figure skating facility in Colorado. I’d been skating for most of my childhood in a sheltered environment–a nurturing coach and small band of skaters who stuck together and provided friendship and support.

The move to Colorado was a shock. I was homesick and ill-equipped to navigate coming of age without parents, siblings or other people looking out for me as a young teenager, and not just a skater. This aspect of the experience left some deep emotional scars, and I never planned to write about them. But then my agent said, hey–maybe it’s time.

Diving into Blade was challenging. I wanted to write a fictional story that aligned with my work in the thriller genre. But I also wanted to capture the parts of my own experience that went beyond describing the skating moves, training schedule, and pressures of competition. It took a few tries to get it right!

During this process of writing and rewriting, I revisited those years in an unexpected way. In order to write the fictional story, I had to capture more than just the darker aspects that had remained with me. I also had to describe the joy that my characters had for skating. In doing this, I rediscovered the joy that I once had, and that is still with me.

So, in the end, it was both clarifying and cathartic!

JBV: “The Palace”—an exclusive and remote training facility located in the mountains of Colorado (not unlike the one you attended)—serves as the book’s setting. How does isolation inform Ana’s sense of self (or lack thereof) and the relationships she forms, both among her peer group and the adult authority figures?

Also, how do the physical constraints of place play into considering the crimes at hand and who may have committed them?

WW: Isolation is a major theme throughout Blade, and the setting was essential in shaping both the characters and the crime. When we first meet Ana Robbins fourteen years earlier, she is leaving home to live in a dormitory with other skaters at The Palace.

The training facility itself is physically isolated in the mountains of Colorado, but Ana is also emotionally isolated—from her family, from normal friendships formed through school, and from a life that exists outside the rink. Instead, she becomes part of an intensely competitive group of young skaters all vying for a limited number of places on the podium each competition season.

That environment helped me explore not only what happens to Ana, but also to the other girls living at the dorm away from their families. The emotional isolation they experience is just as significant as the physical distance from the people who once provided stability and guidance.

The setting also heightens the tension in the present-day storyline. When Ana returns to The Palace as an adult to defend a young skater accused of murdering a coach, the town is cut off by a snowstorm, further separating it from the outside world. The investigation unfolds over just a few days, with Ana working against the clock—alone, in dangerous conditions, and surrounded by the same place that once shaped her. That layered isolation amplifies the suspense and deepens the sense of danger surrounding the crime.

JBV: You use dual timelines as your narrative construct. In what ways does alternating past and present events amplify the book’s mysteries (who killed Emile, what happened to Indy, etc.) while also allowing Ana a unique insight into Grace’s experience(s)? On a more technical level, what is your process like to account for the intricacies of such a complex set-up?

WW: Blade is first and foremost a story about a murder, but it’s equally about what happened fourteen years earlier to Ana and the other girls who called themselves the “Orphans.” Weaving mysteries from the past and present together is one of the most effective ways to build suspense in a psychological thriller—and, for me, it’s a defining element of the genre.

The novel is grounded in the idea that our pasts profoundly shape our futures, which becomes clear when Ana returns to The Palace and is forced to confront what she left behind.

Once I understood that structure, I had an important craft decision to make—whether to reveal the Orphans’ history through flashbacks and internal reflection, or create distinct chapters set in the past. When a story relies heavily on backstory, these choices become critical.

In this case, I chose to devote separate chapters to the past so readers could fully inhabit the characters’ earlier lives, while also experiencing the slow, creeping escalation of danger over the three years the Orphans spend together at The Palace. Dual timelines is one of my favorite tools in psychological suspense, and in Blade, they allowed both the mystery and the emotional stakes to deepen in tandem.

JBV: You demonstrate technical mastery throughout the book when it comes to your depictions of figure skating (for instance, one character’s struggle to land a triple axel is pivotal to the plot). What is your approach to balancing the nuts and bolts of the sport with narrative momentum so that readers believe in your authority without being overwhelmed by it?

WW: This was one of the most challenging aspects of writing Blade! Anytime I’m very close to my subject matter, I have to be especially careful about how much technical detail to include for readers who may have no background in it at all. There was a fair amount of trial and error in finding that balance with this novel—and advice from my agent and editors.

In the first draft, I actually included too little, and was encouraged to add more detail about the jumps and the technical mechanics of figure skating. In the second draft, I was asked to pare those elements back slightly to keep the plot moving forward.

There’s no perfect balance that will satisfy every reader, so the goal is to find the version that serves the story and engages as many readers as possible. That challenge exists in any novel with a specialized setting, and it’s one of the many balancing acts of writing!

JBV: Ana is a criminal defense attorney specializing in childhood trauma. What of your own career in family law were you able to draw on in crafting her character? Conversely, what did you need to research (or brush up on)? And why is it important to understand the machinations of the immature brain in determining criminal culpability?

WW: I went into Blade with a significant amount of knowledge about childhood trauma, much of it drawn from my work as a family law attorney. I was first introduced to the subject while training to become a guardian ad litem—an attorney appointed to represent the best interests of a child in custody disputes.

This training focused on how early experiences shape emotional and psychological development. I learned how various “bumps in the road” during childhood—ranging from accidents and neglect to abuse or the misuse that can occur in contentious divorce situations—can have lasting effects well into adulthood.

When I began writing thrillers about ten years ago, I found myself repeatedly drawn to these themes, and most of my novels explore childhood trauma in some form. With Blade, I did additional research in order to give Ana an authentic voice as an advocate for children accused of violent crimes. That meant engaging more fully with the ongoing debate between nature and nurture.

Because the most damaging psychological conditions often form in the earliest years of life—and are frequently underreported, since caregivers may be responsible—it can be difficult to trace clear lines of cause and effect. I gave Ana a strong point of view on this, summed up in her belief that “children become what we do to them,” which directly informs how she approaches Grace Montgomery’s case. Ana believes that if Grace did murder her coach, then something happened to her at The Palace to create the kind of rage involved in the crime.

JBV: We are entering Olympics season, where young athletes compete among more seasoned veterans. In your opinion, what is important for fans/viewers to keep in mind about the people behind the personas they present on the ice?

WW: When we watch athletes competing, I think it’s important to remember what these people are going through—no matter what age. Athletes who excel in competition have learned to control their emotions under extraordinary pressure—and age doesn’t always matter. I’ve seen very young athletes have “nerves of steel,” and older athletes suddenly crumble under the pressure. Sometimes the pressure is greater if the athlete knows this is their last chance to achieve their lifelong goal.

This ability is one of the hardest skills to master in figure skating, and the reason I made fear a central theme in Blade. Every time a skater steps onto the ice, they know this one moment may determine whether or not they achieve their lifelong goal. This terrifying thought can trigger a powerful fight, flight, or freeze response triggered by adrenaline. And adrenaline interrupts the “muscle memory” skaters rely on to execute their jumps.

These athletes have been skating for most of their lives, and while it’s true that the world’s attention often moves on quickly, many skaters carry these defining moments with them forever. What we’re really witnessing in those four minutes is a young person doing their best under unimaginable pressure.

I always watch the Olympics with my heart in my throat, hoping each skater can quiet that fear long enough to give the performance they want—so that, regardless of where they place, they can move forward feeling proud of how they spent some of the most formative years of their lives.

JBV: Your first novels were contemporary (women’s) fiction. Why did you decide to transition to suspense – and what did you find carried over from one genre to the other vs. had to be learned? Also, what guidance can you offer to those who are considering a similar change?

WW: Here’s the honest answer—when I first started writing, I believed all that mattered was telling a good story. I knew very little about the business side of publishing, including how much genre can influence whether a book ever reaches readers. In 2015, after my first two novels – both considered women’s fiction – failed to gain traction, I was close to giving up on writing altogether and focusing on my law practice.

Before I did that, I thought I should at least try to write one more novel—but to be smarter about the marketplace. At that moment, psychological thrillers were exploding in popularity following the success of Gone Girl and The Girl on the Train.

I decided to try writing in that genre, and with All Is Not Forgotten, I immediately knew I had found the right fit. It aligned perfectly with my voice, my interests, and the things I’d learned about psychology being a family law attorney. That book took off and eleven years later, here we are!

All of that said – I’m hesitant to give blanket advice about writing to trends, because that risks losing originality. I do think it’s important to understand the business—but if a writer has a story they feel compelled to tell, especially one that doesn’t fit neatly into what’s popular, that instinct should matter most!

JBV: Figure skating and writing are disparate activities that share some commonalities in terms of discipline and vision. How have you found that training as a skater has influenced your approach to craft? Also, tell us about how you endeavor to find a sense of personal pleasure and purpose in such activities when the professional outcome is uncertain.

WW: I definitely think the discipline and single-minded focus I learned from skating help me as a writer. Writing is a solitary pursuit—we spend our days alone with our thoughts, staring at a blank screen and trying to build an entire world from nothing. Skating trained me to tolerate that kind of isolation and to show up every day with discipline, sometimes even too much!

Skating trained me to tolerate that kind of isolation and to show up every day with discipline.If you grow up in athletics, that mindset never fully leaves you. You’re wired for delayed gratification, and working relentlessly toward goals that can feel impossibly distant. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve had to learn to ease up on myself and allow space to enjoy what I’ve accomplished and the life I’ve built.

The second part of that question is much harder! Athletes are trained to derive pleasure from achievement—from checking off milestones or completing a rigorous daily routine. That kind of satisfaction is largely internal and often reinforced by external praise.

For many years, I was a workaholic, rarely allowing myself to enjoy free time until everything was done—which, of course, is never! Now I’m trying to shift that mindset. While my career will always carry uncertainty, I’ve found a sense of stability I want to appreciate. I’m actively practicing finding pleasure in small, everyday moments—even something as simple as watching a Netflix episode in the middle of the day after!

It doesn’t come naturally to me, but learning how to rest and enjoy life has become one of my most important goals. New Year’s Resolution—slack off a little! Wish me luck.

***