Back in the 80s, a man being prosecuted for murder by my father, the district attorney, broke out of the county jail and, stranded on the roof of the county courthouse, threatened to kill my entire family. My father decided to go onto the roof himself, where he would eventually talk the man back into custody, but before doing so, he turned to his investigator, an armed ex-cop who would be watching his six while he was on the roof.

“If he moves,” my father said, looking his investigator in the eye, “shoot him.”

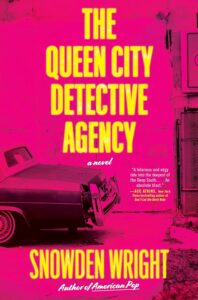

That moment was the inspiration for the first chapter of my latest novel, The Queen City Detective Agency. For years, I heard my father tell the rooftop story, and for years, I heard him recite his hero-moment line—If he moves, shoot him—thinking it was wholly original, that my father had come up with it on the spot.

Then I watched The Wild Bunch. I should have known. My dad loves Westerns, after all.

In the film’s opening, the titular bunch hold up a pay office, and their leader, referring to the tellers being held up, says to his colleagues, “If they move, shoot them.”

The Queen City Detective Agency was born of that transition from Western to crime. It’s a crime novel that, like all crime novels, I’d argue, evolved from the Western genre. Crime fiction’s modern evolution can be traced most directly through the career of Elmore Leonard, who began writing Westerns only to gain his greatest success as a crime writer.

***

The man often called the Dickens of Detroit began his literary career on the streets of the American West. “The desire to write or read Westerns comes more from a feeling than a visual stimulus,” Leonard noted of the genre’s influence on his novels and stories. “Living in Detroit, as I do, wouldn’t seem to be conducive. There sure aren’t any buttes or barrancas out the window. But if you squint hard enough . . . you can see riders coming with Winchesters and Colt revolvers, and watch them play their epic roles in a time that will never die.”

The literary ur-genre of the American Myth, Westerns celebrate and indict the best and the worst in this country, its rugged individualism riding shotgun with genocidal colonialism, heroic masculinity yoked to craven misogyny, and Leonard picked the genre for a fittingly American reason: capitalism. “He chose Westerns primarily because of the market,” Peter Guttridge claimed in The Guardian. “He was in it for the money and sold everything he wrote.”

Leonard’s a truck-and-buck writer. Although he trucks in many of the most recognizable and appreciated tropes of the stock Western—bustling saloons, quick-draw gunfights—he bucks against much of what these days would be called out as problematic. He was ahead of his time even when writing about the past. In Leonard’s novel Valdez is Coming, the titular lead, a Mexican-American forced to code-switch between “Bob” and “Roberto,” seeks restitution for the widow of a Black man he was misled into murdering. Leonard’s other Westerns, including the short story “Three-Ten to Yuma,” twice adapted to the screen, and Hombre, chosen as one of the twenty-five Best Western Novels by the Western Writers of America, established him as one of the genre’s best practitioners—as well as one of its most thoughtful. The women in Leonard’s Westerns lead rich interior lives, and the people from marginalized groups are always, first and foremost, people.

What changed for Leonard? The market. As the 60s moved into the 70s, the Western genre incorporated martial arts (Kung Fu), domestic drama (Little House on the Prairie), satirical comedy (Blazing Saddles), and that soon to be inseparable combination, sex and violence (The Wild Bunch). Leonard loved the movies. In those a-changing times, as Clint Eastwood went from the Man with No Name to Dirty Harry, as the popularity of Gunsmoke defied the typical cause-and-effect of physics by giving way to Bullitt, Elmore Leonard decided to take the advice offered to Woodward and Bernstein. He followed the money.

***

The core dynamic of the Wild West popularized in fiction, with its lawless frontiers and attendant frontier justice, its sheriffs and outlaws, distressed damsels and barons of cattle and railroad, began, I’d argue, with the Civil War, which trained people to kill and numbed them to violence. Subsequently, I would argue, the modern iteration of crime fiction began with the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, which trained people to kill, numbed them to violence, and left them disaffected as all hell.

“With Westerns, I felt I wasn’t using everything I knew,” Elmore Leonard once told the New York Times. “I was in second gear; I wasn’t using what was going on around me.”

In the 1970s there was a lot going on. Aside from the end of the Vietnam War, OPEC’s oil embargo ended America’s “long summer” of economic prosperity, President Nixon resigned in disgrace after the Watergate scandal, the Khmer Rouge took control of Cambodia, Skylab was falling, disco was rising, and in Central Michigan, a small-stakes crook named Jack Ryan got mixed up with the wrong woman.

The Big Bounce, published in 1969, on the cusp of the tumultuous decade to come, introduced Ryan the small-stakes crook and Leonard the big-time crime novelist. He’d found his literary niche, his stool at the dive, flanked by the friends of Eddie Coyle. Under the influence of George V. Higgins, Leonard produced, throughout the seventies, a few of his best novels (52 Pickup, Swag) and some of his most so-so (Unknown Man #89, The Switch), their sepia tones cast in neon, their vistas narrowed into alleys. The morality drama of the traditional Western evolved for Leonard into the immorality drama of crime. Cocktail lounges were the new saloons. Ski masks replaced bandanas. Once a lariat, now cuffs.

For many crime writers, the problematic stereotype of cowboys and Indians became the problematic stereotype of cops and robbers, the easy vilification of Native Americans transitioning into the easy idolization of police officers. Leonard managed to avoid that predicament. Author Frank Gruber outlined seven key plots for Westerns, two of which constitute the bulk of Leonard’s crime fiction: the outlaw story and the marshal story. His bibliography can be subdivided along that same binary. Unlike non-revisionist Westerns, however, Leonard painted his knights-errant of the asphalt jungle in shades of grey. His cops were on the take and his crooks had a code.

That moral ambiguity compounded in later decades, when the Vietnam War became fully enculturated within the American psyche. In those later decades, as well, the influence of Westerns became fully enculturated in Leonard’s crime fiction, much of which proved an old saying: You can take the novelist out of Monument Valley, but you can’t take Monument Valley out of the novelist.

Nowhere is that line more apparent than in the subtitle of Leonard’s novel City Primeval.

***

Recently adapted for television, City Primeval: High Noon in Detroit is the brackish water of both Leonard and America’s shift from Westerns to crime fiction. It blends genres, the saltwater of one sloshing into the freshwater of another, and that’s all the more conspicuous in light of the biggest change FX made to the book when bringing it to the small screen. They retrofitted it for Leonard’s most famous latter-day cowboy.

Raylan Givens appeared in three novels (Pronto, Riding the Rap, and Raylan), one short story (“Fire in the Hole”), and the acclaimed television series Justified, which ran for six seasons. Leonard went full anachronism with the character. Stetson-hatted and stoic, Givens is a man out of time, a quick-draw with a slow drawl, his moral code as stiff as the dead bodies he often deals with. Dude’s more throwback than lookback, and in that way Givens represents the current symbiotic relationship between the genres he straddles. Crime fiction brought realism to Westerns, and Westerns brought idealism to crime fiction. Givens has his boots in both worlds. But what does that signify about the current state of the real world? What does it say of America that its quintessential genre shifted to crime?

For the New York Times, Martin Amis wrote, “Mr. Leonard is as American as jazz, and jazz is in origin a naive form.” But crime novels aren’t naïve; they’re Westerns wised-up. If Westerns are the most emblematic genre of the American Myth—they are to literature and film what jazz is to music—crime fiction is an indictment of the American Experiment.

Elmore Leonard’s career mirrored the decades-long trial of that Experiment. Following the seventies, he finished out the century by exploring what Anthony Lane in The New Yorker described as “the full range of human ineptitude.” Leonard’s work never strayed from the tavern sins of classic Westerns, gluttony and drinking and gambling and lechery, and it also never strayed from the cardinal virtues of classic Westerns: a sense of place and a sense of people. That sense of place was acutely rooted in America. In all his career, Leonard only lost his footing when he stepped away from the dusty, tumbleweed-strewn boulevards of the American psyche: The Hunted is set in Israel, Pagan Babies in Rwanda, Djibouti in Djibouti.

***

Since Leonard’s death in 2013, Westerns have had a minor resurgence, with Leonard’s signature truck-and-buck style. The moral ambiguity, cultural representation, and dynamic female characters that Leonard brought to the crime novel are being brought back to the Western, less the un-interrogated racism and sexism. Anna North’s Outlawed, a Reese’s Book Club pick and New York Times bestseller, reimagines the real-life Hole in the Wall Gang as female and/or non-binary. C Pam Zhang’s How Much of These Hills Is Gold, longlisted for the Booker Prize, follows two Chinese-American orphans during the Gold Rush.

Do the readers of those books know of Elmore Leonard’s direct and indirect influence on the genre? Are the authors aware of a lineage that includes themselves and the Dickens of Detroit? I thought of those questions recently when I was talking with my father about the story on the courthouse roof. If he moves, he’d said that day, shoot him.

“Did you realize you were quoting The Wild Bunch?” I asked my father.

He scoffed. “Snowden, I’ve only seen that movie about two-hundred times.”

“Yeah,” I said, “but did you know you were quoting it?”

My father got serious. He lowered his voice. “Of course not. I was just trying to keep my ass from getting killed!”

That punchline felt like classic Elmore Leonard. He was the man who shot liberty’s valence, the writer who, to the good, the bad, and the ugly, brought the funny. He was a searcher with true grit who crossed the Red River of literary genre for a fistful of dollars.

___________________________________