This is a transcript of a talk that was given, by Dr. Olivia Rutigliano, at the Salmagundi Club in New York City, on September 13th, 2024. The Salmagundi Club is New York’s oldest arts club, founded in 1871. Since 1917, the Club has been located at 47 Fifth Avenue, the last standing brownstone on 5th Avenue.

This speech contains spoilers for the stories “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and “The Purloined Letter” by Edgar Allan Poe and City of Glass by Paul Auster.

*

I want to get something straight before we begin.

There’s no such thing as a detective. Detectives are not real.

Not in the sense that we have come to know them, culturally–as gentleman sleuths, or gritty PIs, or antisocial savants, or tortured consultants or what have you–individuals who spend their days and even make their livings chasing serial killers, tracking down thieves, or solving impossible puzzles.

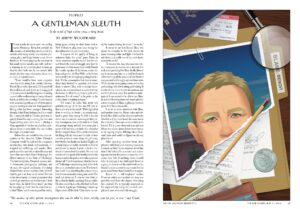

This (the fake New Yorker article from Knives Out, profiling Beniot Blanc as “the last of the gentleman sleuths,” doesn’t happen in real life. There are no gentleman sleuths in real life.

This isn’t to say, of course, that in real life we don’t have people who perform versions of that work–private investigators or dogged journalists or solutions-focused researchers or in-house spies or, even in some cases, true crime podcasters. And of course, there are many types of police detective and federal agent whose work it is to solve murders and thefts and other crimes.

But there is a great difference between these real-world figures and the ones of fiction. It seems silly to even say that “reality” and “fiction” are different when it is implied by their very definitions, but to probe deeper into this difference, however obvious, is to discover the particular nature of the type of fiction involved: the detective story. “The detective story” is not like other works of fiction just as much as it is not like reality; it operates within unique formal constraints.

The great mystery writer Dorothy L. Sayers warns us,

“There is the whole difficulty about allowing real human beings into a detective-story. At some point or other, either their emotions make hay of the detective interest, or the detective interest gets hold of them and makes their emotions look like pasteboard.”

In other words, the detective story is an alternate reality in which investigation offers a kind of existential lifeline, and, even if characters confront the depressing nature of murder or other crimes, they are distracted or healed by the process enough to stave off the kind of trauma that would exist in the real versions of those circumstances.

Sayers and others have outlined that, to accomplish this, the detective story is principally driven by two things: plot, and expectation. Sayers even goes so far as to say that Aristotle, who believed in the primacy of plot above character, would have been a fan of detective fiction (though not procedurals, because he did not like episodic entertainment).

Speaking to the former… in 1958, the critic A.E. Merch defined the detective story as “a tale in which the primary interest lies in the methodical discovery, by rational means, of the exact circumstances of a mysterious event or series of events.”

The great fiction writer G.K. Chesterton defined the novel somewhat differently, speaking to the latter element in an essay from 1930: “The detective story differs from every other story in this: that the reader is only happy if he feels a fool… the essence of a mystery tale is that we are suddenly confronted with a truth which we have never suspected and yet can see to be true.”

Indeed, the classifying principles of “a detective story” are so formalized and strict, that they, themselves, are the main draw of the whole enterprise

In his famous 1944 essay for The Atlantic entitled “The Simple Art of Murder,” Raymond Chandler argued that there is very little difference between a good detective novel and a bad one, because, as detective novels, they are rather the same.

Thus, the protagonist of “the detective story,” the detective, is made possible by those same strict parameters which govern the rest of the story. The detective is part of the fabric of that world, a world which generates puzzles that only a few brilliant minds can see, and solve, despite the fact that these puzzles appear in specific, similar patterns as these stories multiply. The detective story offers a heightened world in which the intellectual work of puzzle solving can have the most significant practical effects.

I wrote an essay recently on the aesthetic phenomenon in detective procedurals on television, in which an Ivy League or Oxbridge-educated scholar becomes a detective, and thereby puts all these miscellaneous, humanistic and intellectual pursuits to pragmatic application. This detective quotes Shakespeare and is a fan of the opera, making him an ideal foil to the inevitable psychopathic serial murderer who leaves riddles in the form of Shakespeare quotes and opera references. Indeed, such shows seem to suggest an answer to the question, what is one to do with a humanities degree? In detective stories, the greatest and best-educated minds find a nobler job than simple scholarship: they put that knowledge to work solving puzzles for the greater good. Very few such circumstances exist in real life.

And almost all detective characters are cast in this mold. The trope of the well-educated detective is an example with parameters so exaggerated that it’s clear how much “the detective” is an idealized figure. But all detectives in these stories, regardless of education or background, follow a higher calling: of truth, with a capital T. This doesn’t necessarily mean they are moral arbiters, but that they follow a kind of north star of… factuality or validity.

Thus, the “detective,” as we have most commonly come to know them, is a literary conceit, but it is a really good one. And its specialness is clear by the fact that it was invented simultaneously with the creation of a job called “detective” but veered away from the lackluster, pedestrian qualities of that job, towards something intellectual.

This happened in the first half of the 19th century. Since this is a Frederic Dorr Steele Memorial lecture, I’m keeping our discussion to the Western world, specifically Britain and America. When it was created in Britain in 1842, the profession of “detective” simply meant “plainclothes policeman” and didn’t involve investigation, so much as rounding up and intimidating criminals and arresting those presumed to have committed crimes. But the potential of this figure to do penetrating intellectual work into the nature of truth, took hold in the culture, and produced a variety of different types of detective, including some of the archetypes I mentioned earlier.

As I said, the cultural imagining of the detective quickly surpassed the nature of its real-life counterparts. In the early 1860s, twenty years after the Detectives Division of London’s Metropolitan Police was created, and before many of the first male detective characters were brought to life on the page, a writer named William Stephens Hayward created a character named Mrs. Paschal, who works for an all-female detective branch of the London Police. But at this time, women were not allowed to join the force at all, would not be, until the twentieth century. Detective fiction was so full of potential for characters to become their most intellectual, capable versions, that it allowed for the imagining of an alternate world, reconstructing the social order for the sake of a good story, giving professional equality and agency to a group long denied those things. (There is much to say about Victorian lady detectives, especially because their ability to do rationally-coded, intellectual work is treated as anomalous, as women were thought to be emotionally, as opposed to be intellectual, coded figures. But that’s another conversation for another day.)

What is it about the detective that took such a foothold in our culture one hundred and eighty some-odd years ago and only continued to anchor itself in it? Countless scholars have attempted to map out this interest and popularity.

George Grilla has written, “Most readers and writers of detective fiction claim that the central puzzle provides the form’s chief appeal. Every reasoning man, they say, enjoys matching his intellect against the detective’s, and will quite happily suspend his disbelief in order to play the game of wits.”

But I argue that the most important feature of the detective story is not simply the puzzle, but the fact that there is a detective at all. Because a detective is a figure unlike any other in literature, and every figure in literature is a little bit of a detective.

And today, I’m going to take you through three theories of “the detective,” and present case studies for each, with the goal of emphasizing just what it is that the detective offers to our culture, and begin to account for why the figure has remained so significant.

The first theory of the detective is the oldest and most well-known. It’s “the Detective as Reader.”

The Detective as Reader…

For a moment, let’s go to Paris. Paris in the 1840s. Paris in the 1840s inside the mind of Edgar Allan Poe.

A terrible double-murder has taken place one evening in a home along the Rue Morgue, which is a street in the second arrondissement of Paris. The victims are two women, Madame L’Espanaye and her daughter, Mademoiselle Camille L’Espanaye. The body of the younger woman is found stuffed inside a chimney. She has marks on her neck from strangulation. Her mother’s body lies in the backyard, with many broken bokes, a mutilated face, and a clump of reddish hair in her fist. She has such a deep gash in her throat that when the police lift the body up to carry it away, her head falls off.

The neighbors on the street had been awoken at night by screams—about “eight or ten” neighbors and two gendarmes had, together, forced themselves inside to see if everyone in the home was all right. Running up the stairs, they still hear noises from somewhere above, but by the time they reach the fourth floor, everything has gone silent.

The police determine that the murder took place there—on the fourth floor of the house, which has been thoroughly ransacked and where strange pieces of evidence remain: tufts of gray hair on the fireplace, gold coins all over the floor, and a straight razor, which is by now covered in dry blood, lying on a chair. A safe is open. But the room is locked. The police and neighbors broke down the door to get inside.

The police speak to many witnesses, who explain that they heard several voices coming from the house. One voice was male and was speaking French (which they know because they heard someone cry “mon dieu”), but no one can agree on the language that the other speaker used. The police are baffled.

This is the premise of the mystery at the center of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” which was published in Graham’s Magazine in 1841. And it is thought to be the first true, the first pure, the first modern detective story in history. Which makes that story’s detective, Le Chevalier Auguste Dupin, the first modern detective.

Dupin is a young man, from a once wealthy family. He is presented to us by the story’s unnamed English narrator. They meet searching for a book, in “an obscure library in the Rue Montmartre, where the accident of our both being in search of the same very rare and very remarkable volume, brought us into closer communion.”

The narrator says of Dupin, “Books, indeed, were his sole luxuries, and in Paris these are easily obtained.”

The two strike up a friendship, and since the Englishman does not have permanent lodgings for his stay, they agree to live together. They move in together, in “a time-eaten and grotesque mansion… in a retired and desolate portion of the Faubourg St. Germain.”

And it is there where, one morning, Dupin and his friend open up a newspaper, the Gazette des Tribunaux, to learn about the ghastly horrors that took place in the house on the Rue Morgue.

And after reading everything—the testimonies, the descriptions— Dupin asks his friend what he has made of all of this. His friend doesn’t believe that it’s possible to figure out the identity of the killer from any of the evidence. Dupin begs to differ. Friends with the prefect of police, he is allowed to enter the crime scene. Dupin walks around, narrating what he is seeing.

As he does with his books, he reads the crime scene. And then, right there, he solves the mystery.

As the first major detective in literature, Dupin sets a precedent for the detective character, aligning the general methodology and work of the detective… with the general work and methodology of the reader. Not in the sense that the reader and Dupin are racing to find the answer, but that Dupin approaches the crime scene the way a reader approaches a book.

Both detectives and readers mine the evidence presented for meaning, interpreting that material, and drawing a conclusion from it. The crime scene, the dead body, the open safe… those are the detective’s texts.

As such, the detective mirrors the entire field of literary scholarship, mimicking the work that scholars do, starting with a practice known as “close reading.” No one really knows when that term came about, and there has been some debate as to its precise meaning, with many scholars regarding it as a catchall term for numerous methodologies of deeply understanding a text, all of which involve zooming in on specific details, like sentence structure, word choice, or even punctuation placement.

But it is one of the most important ways to understand the main arguments and subtext, alike, of any text.

When the detective is a reader, the work that the detective does is clearly represented as a process of identifying and interpreting meaning… this figure is highly reactive, so much so that the detective isn’t even necessarily the protagonist.

In the “howcatchem,” the style of mystery like Columbo or Poker Face that shows the killer committing the crime at the start, the murders are arguably the protagonists, and the detective are their antagonists, showing up later, and responding.

Let’s move onto the second category, “the Detective as Writer.”

The Detective as Writer

Now, let’s go back to New York City… but New York City in 1985. New York City in 1985 inside the mind of Paul Auster.

“It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.” This is the first line of Paul Auster’s short story “City of Glass,” from his collection of inside-out detective stories called The New York Trilogy.

The “he” in question is Daniel Quinn, a writer of detective fiction under an assumed name. That name is William Wilson, the same name as the protagonist of a proto-detective story of Edgar Allan Poe’s from 1839. Poe’s story is about a man, William Wilson, who is driven mad by his own doppelgänger, and who does not realize until he fatally stabs him, that his doppelgänger was actually his own reflection—himself. William Wilson is the name of Quinn’s alter ego, and Wilson is the author of detective stories about a sleuth named Max Work. And one night, when he is home alone, Daniel Quinn gets a phone call from a strange individual who asks to speak with a detective.

But not just any detective.

“Hello?” said the voice again.

“I’m listening,” said Quinn. “Who is this?”

“Is this Paul Auster?” asked the voice. “I would like to speak to Mr. Paul Auster.” “There’s no one here by that name.”

“Paul Auster. Of the Auster Detective Agency.”

“I’m sorry,” said Quinn. “You must have the wrong number.” “This is a matter of utmost urgency,” said the voice.

“There’s nothing I can do for you,” said Quinn. “There is no Paul Auster here.”

Except of course, there is.

In writing “City of Glass,” Paul Auster the writer collapses numerous versions of the same man on top of one another, burrowing them deeper and deeper into degrees of fiction, and then pulling them all back towards reality again –the fictional writer Quinn, his fictional alter-ego Wilson, his fictional detective Work, the detective Paul Auster, and (we’ve looped around), the writer Paul Auster.

Quinn realizes, a bit later on in the story, that he should accept the call and claim to be Paul Auster. This is his rationale:

“The detective is one who looks, who listens, who moves through this morass of objects and events in search of the thought, the idea that will pull all these things together and make sense of them. In effect, the writer and the detective are interchangeable.”

In stories like this, ones that collapse the detective and the writer, the argument is usually that, rather than the detective identifying and interpreting meaning, the detective is making meaning.

And these are different things. When the detective is a reader, the entire narrative has already been decided for them. They follow it, trace it. When the detective is a writer, the entire narrative is up to them.

To be clear, I’m not talking about characters like Jessica Fletcher from Murder She Wrote or Richard Castle from Castle… detectives who work as writers but principally whose detective work involves them functioning as readers. No, in this section, I am referring to detectives who manufacture their own narratives of detection.

What does the detective-as-writer look like?

Here’s a short video I’ve prepared:

With the detective-as-writer, the detective does not simply find the connections, follow the narrative, suggested by various elements. No, the detective as writer puts together a story around those elements; offering a level of participation and agency not seen when the detective is merely a reader.

Often, in stories like this, the detection process is a way for the detective to rewrite his or her own story, or purpose. Perceiving and then attempting to solve a mystery are processes entwined with the writer’s own imagination and desires.

Indeed, the main difference between the detective-as-reader and detective-as-writer is that the former’s job is to make sense of the narrative already propelled into one by the killer or criminal… but the latter, the writer-detective, is the one propelling the narrative.

Now, let’s move onto the final category, “the Detective as Illustrator.”

The Detective as Illustrator

Time for our third category… and this brings us, finally, to a theme resonant with the design of this event, because it is exclusively the provenance of visual storytelling. We’ve been going in chronological order, from the advent of the detective story, with Poe, to Auster’s postmodern reworking of it, to new media’s approach to it.

“The Detective as Illustrator” is a bit more abstract of a concept, a bit difficult to explain, compared to the two previous categories I mentioned.

When the detective is a reader or writer, the focus of the corresponding work is on the results and effects: for the former, the reading of the scene and the production of an answer. For the latter, the manufacturing of a story around a series of events and the redemption of one’s own involvement in it.

But this third category does not look at the external results or effects of or reasons for detection, but rather the process of detection as it happens internally within the mind of the detective. And then, it externalizes, dramatizes, that psychological, intellectual process. Stories about the detective-as-illustrator are concerned with representing in visual terms the mental process of solving and understanding a mystery, a process that is fundamentally impossible to fully impart to others, or for others to fully know.

And by the way, the detective-as-illustrator can overlap with the previous two categories; the essence of its categorization in a third silo is its presentation.

Many different media versions of detective stories grapple with how to undertake an illustration of this abstract nature; indeed, the form of the novel easily allows the representation of the internalized processes of thought. So how do visual media accurately capture, sufficiently conjure, this process?

The detective-as-illustrator attempts to map out visually what it is to think, and think hard. Take a look:

Here’s another video I have prepared

This visual element offers a take that the process of deduction is actually the most essential to the detective story—if it were not so central to account for the detectives ability to solve the puzzle, why else would it be represented to such an extent—or, rather, why would it be so crucial not to leave out?

The process of detecting is called, according to Poe, ratiocination, and without this, there would be no detective story, because without it, there would be no detective. This particular visual intervention helps to resent the subject of countless debates and discussions about the most essential elements of the genre the thinking, deduction itself. But it represents it as a craft, an art—emphasizing the freedom of thought, the creativity, and even the artistry of a process that takes place in the mind, but benefits the greater good.