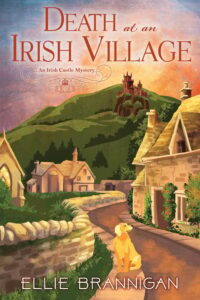

While writing the third Irish Castle mystery, Death at an Irish Village, where cousins Rayne McGrath and Ciara Smith are tasked with bringing Grathton Village into the modern era, I discovered the Jewels of the Order of Saint Patrick, otherwise known as the Irish Crown Jewels, had been stolen on July 6, 1907, and never recovered. Not even a hint of their location was given by the thieves. Though under lock and key, it was as if the jewels had vanished into thin air. A thousand-pound reward was offered. Images of the jewels were released twice a week in the newspaper. Items taken? A diamond badge, a diamond star, and five jeweled collars created for the Irish to be part of the royal knighthood, like the Scottish Order of the Thistle, and the English Order of the Garter, this would be the Irish Order of Saint Patrick. It was established in 1783 by King George III and the jewels used were from Queen Charlotte’s collection.

The Dublin Metropolitan Police were so desperate to get these back that they even used psychics, to no avail. The value of the jewels today could be well over five million pounds.

Who was in charge? The Ulster King of Arms, Sir Arthur Vicars, was head of security in Bedford Tower, where the jewels were housed. There were rumors the guard had taken them, but to his dying day, Vicars maintained his innocence. His lifestyle didn’t reflect added affluence after he was forced to resign from his position. Vicars liked to drink and then show off the jewels to visitors which made him a very easy scapegoat.

Other possible suspects were Francis (Frank) Shackleton, Vicars’ second in command, and the Dublin Herald of Arms, as well as Army Captain Richard Gorges—both rumored to be gay. At that time, homosexuality was a crime, and tales abounded that the truth of the theft was suppressed by the Royal Irish Constabulary to protect those in government. Detective Chief Inspector John Kane of Scotland Yard is said to have named the culprit in his report, but it was never released. Squashed like a bug, which makes me lean toward the scandal theory. Or was that a double coverup to throw one set of folks into the spotlight, and protect another? Detective Chief Inspector Kane cleared Shackleton, and the blame was placed on Vicars for not being a good custodian of the jewels. He and his staff were all released from duty.

A false accusation was made by the London Mail in 1912, stating that Vicars had a mistress to assist in the theft—she’d copied his keys and taken the jewels to Paris. Vicars sued the paper for libel and won.

Another theory went that the jewels had been hidden inside Bedford Tower somewhere and weren’t stolen at all—as a prank? As a protest? In 1983, the now Republic of Ireland vacated what was once the Office of Arms, and the premises were carefully torn apart from walls to floorboards. No jewels were found.

There is no record of them being sold or broken apart. There was so much political unrest during that period in Ireland. What if stealing the jewels was a protest from Irish rebels against Britain’s hold? The decorative pieces for the Order of Saint Patrick were created to signify unity between the countries. This struck a chord in me—and I am not the only writer to be affected by the unsolved crime.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes series, was distant cousins with Sir Arthur Vicars and so intrigued he offered to help with the police investigation. It is believed that his short story, The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans, was inspired by the theft of the jewels. The jewels on the page were swapped with secret submarine plans and of course, Holmes solves the case. There are several other fictionalized stories that reference the mystery.

In the Irish Castle series, Rayne, a Hollywood bridalwear designer, and her cousin Ciara, inherit a rundown McGrath Castle, which has been in the family since 1750. With only six months left before the deadline in Uncle Nevin’s will, they are crunched for time. Not all the villagers are on board with change, though the property is perfect for a high-end wedding venue. Envision rolling green hills, churches, and picturesque graveyards. Father Patrick O’Murphy encourages them to clean the cemetery and prove their willingness to work hard. The thriving community, now only five hundred inhabitants, is about to age out with many of the villagers in their seventies, eighties, and nineties. It’s imperative the cousins succeed before they’re swallowed up by neighboring Cotter Village, and councilwoman Freda Bevan.

The young ladies were constantly told that the McGraths were heroes. In a rescued trunk from the attic, Rayne and Ciara discover a bunch of photos but a black-and-white polaroid dated 1921 of four soldiers with no names captures her attention. Who were these men? As she digs, Rayne fears their ancestors had secrets that might not put them in a respectable light. There’s an emblem with a shamrock on a cloud. It will turn out to be a shamrock on an inverted crown—a symbol of Irish freedom.

I wanted to tie in what was happening during 1921 with Rayne and Ciara in modern day, and the stolen Irish Crown Jewels. Threads can be like spun sugar, delicate and out of order, but the story must come together in a satisfying manner.

Unionists wanted to remain part of Britain, but what about the political factions that didn’t want unity and were willing to die for freedom? I couldn’t get the question out of my mind. The IRA killed Vicars, execution style, before burning his home. Rumors swirled that he’d been an informant to the crown, though it was an unlikely scenario. What if he’d been protecting someone, and now that person was no longer in play? What if he really did know the truth, and that truth would rock Ireland’s newfound freedom? What if?? He had to be silenced before he could talk.

The Order of the Thistle, the Order of the Garter, and the (now defunct) Order of Saint Patrick were formed to create a group of chivalrous knights with integrity and honor. In Death at an Irish Village, I fabricated the Cavalier Clovers to be brave warriors hell-bent on justice for Ireland. The McGraths, McGillicuddys, Dennehys, and O’Briens, all still had ties in Grathton Village. The Cavalier Clovers stole those jewels to fund freedom for the Republic of Ireland, and left clues—if one knew how to decode them. As the older generation died off, the younger didn’t understand what they’d been protecting. This solution honored the McGraths of old and gave a plausible answer to what another secret group may have used the jewels for—freedom—blending fact and fiction.

The joy of writing is balancing the what-ifs with truth, to entertain and thrill.

What really happened to those infamous jewels? We may never know.

***