Unlike me, not every reader has been a die-hard fan of mystery fiction for decades. More likely, you are a fan (else why would you be on a site titled CrimeReads?) but not totally devoted to the genre and basically just looking for some recommendations of what to read but unsure about the various categories by which books may be defined. As a geek who has been professionally involved with crime fiction for nearly a half-century, maybe I can help.

I tend to embrace a wide range of fiction into the mystery genre, defining it as any work of fiction in which a crime or the threat of a crime is central to the theme or plot. This includes the form that most readers regard as a mystery, which is the traditional detective story but a category of literature that also includes the police procedural, the hard-boiled novel, the tale of psychological suspense, the crime novel, and the thriller. There is enormous overlapping of these sub-genres and it is often difficult to categorize some books.

It is my plan—indeed, my mission—to define these categories, describe their strengths and weaknesses, and provide numerous examples from both the past and the present to help guide readers to the type of book they are most likely to enjoy.

This is the fifth of several columns in which I try to define the major sub-genres. Number one was about the Traditional Detective Novel, and number two focused on Hard-Boiled Fiction, the third focused on the Thriller, and the fourth on the Police Procedural.

Today, I’d like to discuss the crime novel, which has become increasingly popular in recent years.

THE CRIME NOVEL

The major element that most clearly distinguishes the crime novel from the rest of mystery fiction is that there is, in fact, no mystery. It is a depiction of criminal life, and it is told from the viewpoint of the criminal. It is not very much a “whodunnit” but more of a “whydunnit.”

STRUCTURE: There are various forms of the crime novel, some very dark, some humorous. A criminal sets a career path and decides to become a burglar or a gangster in one type of book. In another, the primary focus is the analysis of a psychopathic or anti-social figure.

In its earliest form, the crime story was about Robin Hood figures, or bandits. These were refined to become stories about gentlemen crooks, epitomized by Raffles, the amateur cracksman, and other charming rogues who stole, mainly from people who seemed to deserve it. It was common for these shady characters eventually to go to the other side and either detect crime or prevent it.

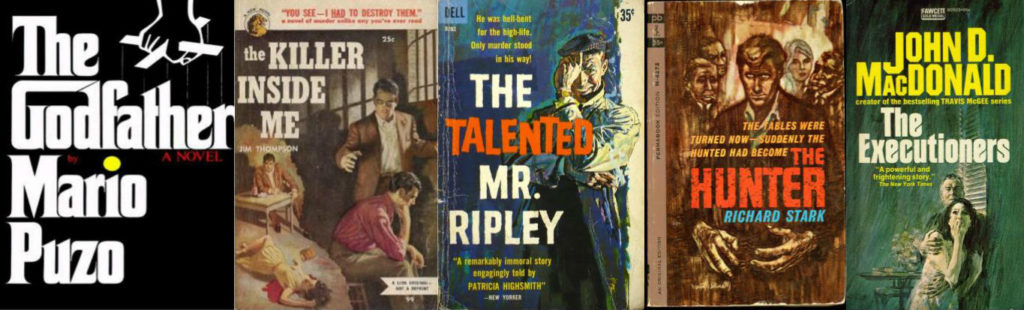

With the advent of organized crime in America, gangster stories became both possible and popular. People wanted to read about Al Capone and John Dillinger, whether in the daily newspaper or in idealized fictional form. In later years, Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, with its apparently realistic (although completely fictional) depiction of life within the Mafia became the best-selling crime novel of all time.

Noir fiction, too, spoke to a nation beaten down by the Great Depression, opening the door for James M. Cain, Horace McCoy, and their nihilistic comrades, joined in later years by Jim Thompson and his vicious killers and Elmore Leonard and his charming ones.

HOW TO TELL: Certain titles or dust jacket descriptions are obvious. When the focus is on a robbery, a caper, or some other illegal activity, and not on anyone whose job it is to solve or prevent it, the book is clearly a crime novel. If, in spite of horrific events on either a massive scale or a personal one, the author has not attempted to make any moral judgment, or if an author refuses to be regarded as a mystery writer, but as one who merely desires to examine criminal themes, chances are the result will be a crime novel. Detective fiction has stringent moral values and tends to be philosophically conservative; crime fiction tends to be radical, or at least anti-establishment.

THE BEGINNING: Such mainstream novels as Les Miserables and Crime and Punishment have little to do with detective fiction, even though they feature hard-working, relentless, policemen. We know who did it. The question is why they did it, and what effect it had on the perpetrators. If one wants to stretch a point, the first crime story occurs in Genesis, the first book of the Bible, in which Cain murders his brother, Abel, and a rich history of crime fiction persists through the ages, from Oedipus Rex to Macbeth to almost all the major works of Charles Dickens.

THE GREATS: One type of crime fiction was exemplified by James M. Cain, in such novels as The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity, in which passion overcomes reason and unappealing people plot murders for sex or money or both. This is a common thread of many classic noir novels and the films made from them, such as Geoffrey Homes’s Build My Gallows High (filmed as Out of the Past), Richard Stark’s The Hunter (filmed as Point Blank), and Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley series, notably The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Although such classics of hard-boiled fiction as The Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep, and I, the Jury, are often referred to as noir novels, they are diametrically opposite. The private eyes Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and Mike Hammer, as well as most all private dicks who followed, had a powerful sense of justice (though not one that necessarily conformed to the legal system). The central characters in noir fiction were doomed to punishment because of their own moral bankruptcy. Driven by their own selfish desires, whether for money, sex, or revenge, their futures were bound to be hopeless, with the inevitable punishment of death, incarceration, or loneliness.

Other popular crime novels showed criminals planning and executing robberies. W.R. Burnett’s The Asphalt Jungle, and High Sierra are examples, as are Jim Thompson’s The Grifters and Lionel White’s Clean Break (filmed as The Killing). While these are dark, the same structural elements may appear in comic novels, usually capers, such as Eric Ambler’s The Light of Day (filmed as Topkapi) and Donald E. Westlake’s always humorous works, notably those about John Dortmunder and his gang (The Hot Rock, Jimmy the Kid, and Bank Shot).

Naturally, prison and gangster stories fall into the crime novel category, including such famous novels as Burnett’s Little Caesar, Puzo’s The Godfather and Horace McCoy’s Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye.

Stories featuring psychopaths are related, quite obviously, to the crime novel, too, such as John D. MacDonald’s The Executioners (filmed twice as Cape Fear), Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train and Davis Grubb’s Night of the Hunter.

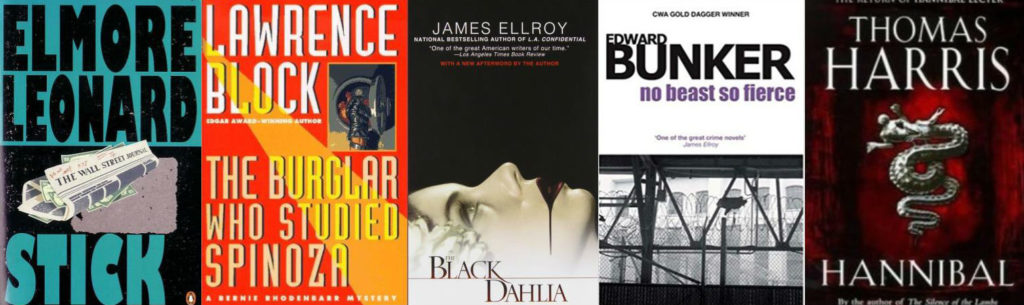

BEST OF THE MODERNS: Elmore Leonard tops any list of writers about criminals, both petty and major. While the brilliant Thomas Harris can’t be ignored because of his creation of Hannibal Lector, his books are mainly told from the point of view of the FBI agents who hunt “the Cannibal” and his idolators. Westlake continued to write the funniest crime capers of all time until his death in 2008. Lawrence Block’s Bernie Rhodenbarr series features his activities as a burglar, though he spends a lot of time solving crimes, too. His hit man, Keller, is a different story, with a character as amoral as Highsmith’s Thomas Ripley. While James Ellroy writes about cops, particularly in Los Angeles, there are so many corrupt and violent characters that his work is closer to the crime novel than to mystery fiction. No one has written better prison fiction that Eddie Bunker (No Beast So Fierce, The Animal Factory).

As the constraints of the traditional detective story have become less appealing to a large number of readers, and even more to writers who find the form so difficult, it is safe to say that there will be a greater percentage of crime fiction on the horizon in the years ahead–for better or worse.