Unlike me, not every reader has been a die-hard fan of mystery fiction for decades. More likely, you are a fan (else why would you be on a site titled CrimeReads?) but not totally devoted to the genre and basically just looking for some recommendations of what to read but unsure about the various categories by which books may be defined. As a geek who has been professionally involved with crime fiction for nearly a half-century, maybe I can help.

I tend to embrace a wide range of fiction into the mystery genre, defining it as any work of fiction in which a crime or the threat of a crime is central to the theme or plot. This includes the form that most readers regard as a mystery, which is the traditional detective story but a category of literature that also includes the police procedural, the hard-boiled novel, the tale of psychological suspense, the crime novel, and the thriller. There is enormous overlapping of these sub-genres and it is often difficult to categorize some books.

It is my plan—indeed, my mission—to define these categories, describe their strengths and weaknesses, and provide numerous examples from both the past and the present to help guide readers to the type of book they are most likely to enjoy.

This is the second (last time I covered the Traditional Detective Story) of several columns in which I try (you can decide with how much success) to define the major sub-genres. Today—

THE HARD-BOILED NOVEL

Ever since I was an English major at the University of Michigan, it has been my position that writers of mystery fiction have produced some of the finest and most enduring literature of the 20th (and now 21st) century. As a voracious reader for more than a half-century, I have experienced nothing to change my mind on that score.

It is with hard-boiled fiction that literature bloomed most eloquently and colorfully. While it cannot be argued that Ernest Hemingway was the most influential writer of the 20th century, there is evidence to suggest that he was influenced by Dashiell Hammett, the first of the great hard-boiled writers.

James M. Cain, the quintessential hard-boiled writer, claimed he didn’t know what that meant, and he wasn’t alone. So what is it? Mainly, hard-boiled stories involve private investigators as the hero (though Sherlock Holmes was a private eye and the stories aren’t hard-boiled, and Cain never wrote a detective novel). They are realistic, in the sense that people who go out and get a private investigator license are hired to solve crimes, which is more than the village vicar or the head of the gardening club can say.

P.I.s need to be tough, since they are dealing with killers, so in the books about them, they act tough and talk that way, too. They are American and they are loners, much like the old gunslingers of the West. They have a code of honor and justice that may not be strictly legal, but it is moral. They may be threatened, or beaten, but they won’t give up on a case or betray a client. They are individuals, often matched against a corrupt political or criminal organization, but they prevail because they are true to themselves and their code.

STRUCTURE: The private eye novel has strictures tighter than a sailor on his first night of shore leave. In a narrative commonly told in the first-person form, someone, frequently a young woman, comes to the office of a shamus because she’s in trouble. The police can’t or won’t help, or the situation is so sensitive that an investigation needs to be kept secret.

The dick takes the case, which is invariably about something more than he was told. He interviews people and learns secrets, frequently about events in the distant past. He is usually betrayed by one or more people, often his client, which, being a cynic, doesn’t surprise him. By the time he concludes his investigation, there generally have been several more murders along the way as people attempt to keep secrets hidden. He turns over the culprit to the police, and continues with his lonely life, awaiting the next meager payday.

HOW TO TELL: A snap-brim hat, a trench coat, and a frosted-glass office door may well appear on a dust jacket, even though they are utterly anachronistic. If a handgun isn’t illustrated, be surprised. The flap copy may include such words as dame, P.I., dick, shamus, for hire, and “a case for.” The cover is probably dark, with a lonely street or storefront, possibly with rain.

BEGINNING: The hard-boiled detective was created in the pages of “Black Mask” magazine in the early 1920s by Carroll John Daly, a largely forgotten hack. He was immediately followed by Hammett, who brought real talent to the genre and gave it literary credentials. Daly also created the first series private eye, Race Williams, and remained more popular than Hammett for more than a decade. Daly is largely unread today while Hammett, rightly, is taught in universities.

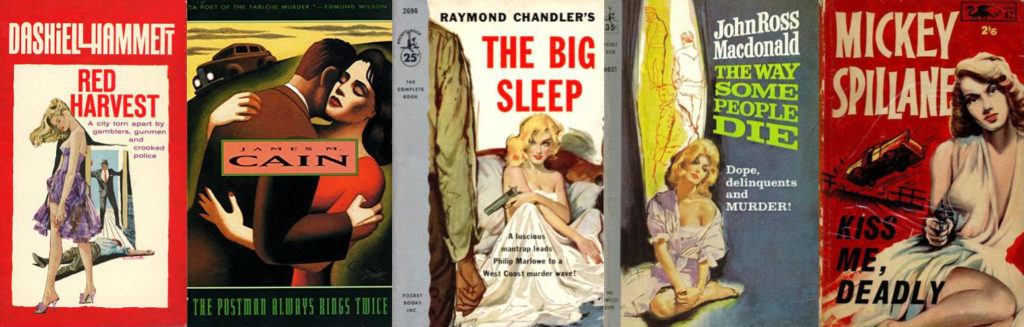

THE GREATS: Hammett’s unnamed P.I., the Continental Op, appeared in numerous short stories and his first two novels, Red Harvest and The Dain Curse, before he created Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon, which remains, in many ways, the ultimate private eye novel. It remains imprinted on the memory partially because of the splendid Humphrey Bogart movie. The only other novels Hammett wrote were The Glass Key, perhaps his finest book, and The Thin Man, which is a fairly dark and tortured novel, unlike the comic film based on it.

Raymond Chandler followed Hammett with his immortal Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep and eight subsequent novels. As a pure writer whose use of simile and metaphor has never been equalled, Chandler remains one of the giants of 20th century literature. When Ross Macdonald decided to write P.I. novels about Lew Archer, he emulated Chandler’s style as closely as he could, eventually adding Freudian psychology to give his novels a depth rarely achieved before or since.

Mickey Spillane, whose vigilante hero Mike Hammer made him the most popular writer in America for a decade, was the toughest of them all, and perhaps the best plotter as well. Reviled by critics for his black-and-white views of justice, readers nonetheless loved his clarity of vision and he became a great favorite of the objectivist philosopher Ayn Rand.

Other outstanding hard-boiled writers include Erle Stanley Gardner (whose Perry Mason stories sold more than a hundred million books), Howard Browne (also writing as John Evans), Harold Q. Masur, Thomas Dewey, Jonathan Latimer, William Campbell Gault, Frederick Nebel, Paul Cain (his Fast One remains a towering achievement), Raoul Whitfield, and, later, George V. Higgins.

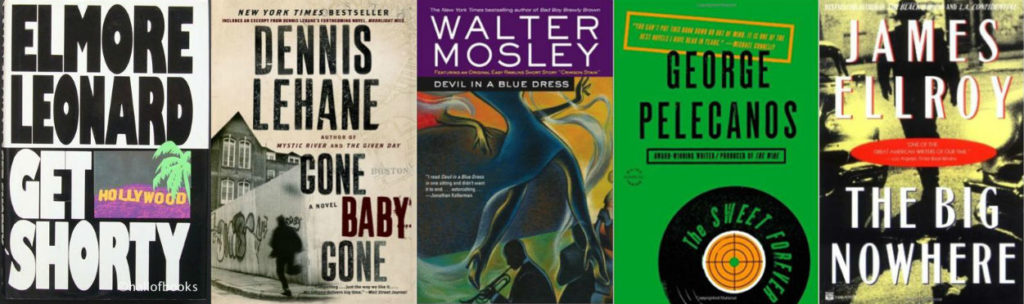

TODAY’S BEST: Among the finest writers in any field over the past four decades has been James Crumley, whose The Last Good Kiss can be reread endlessly with pleasure. Robert B. Parker has justly been placed in the pantheon of greats for his Spenser novels. Dennis Lehane is as good as it gets.

Other terrific hard-boiled writers, who may or may not feature private eyes, include Michael Connelly (whose cop, Harry Bosch, is a policeman who often works as a private investigator by circumventing police procedure), Elmore Leonard, George Pelecanos, James Ellroy, Loren D. Estleman, Reed Farrel Coleman, Walter Mosley, and the unjustly neglected Stephen Greenleaf.

Most of this column has been devoted to the hard-boiled private investigator, but hard-boiled prose has been employed by outstanding writers of suspense, such as Cornell Woolrich, who wrote the best suspense stories since Edgar Allan Poe; by writers of crime fiction, who often told stories from the criminal’s point of view, such as James M. Cain, Jim Thompson, W.R. Burnett, David Goodis and Richard Stark (Donald E. Westlake’s pseudonym); and by those who write police novels, including Ed McBain, William J. Caunitz, Stephen Solomita, and Joseph Wambaugh.