After I recently lamented on social media about how much I miss used bookstores, a couple of people pointed out that I could get used books here or there. They usually cited those used books superstores like Half Price Books.

I replied that I’m not looking for used books – I’m looking for a used bookstore.

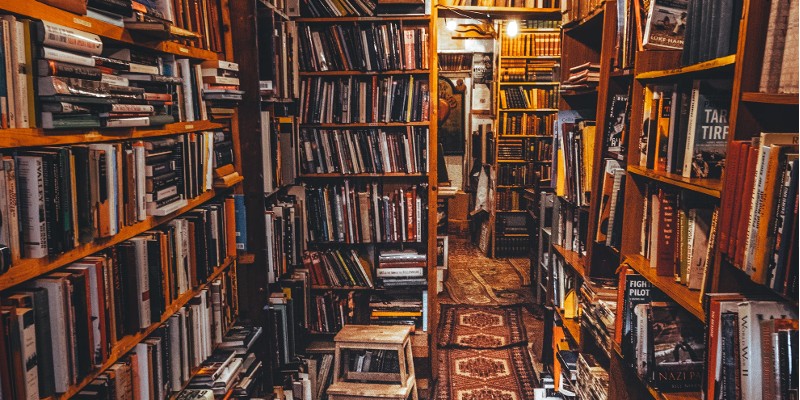

It’s probably an odd distinction, but used bookstores had an aura – yes, probably dust and yellowing paper, but also an aura of possibility. Would you find your new favorite book among 50 copies of some bestseller from 25 years ago?

I was spoiled for great used bookstores when I was younger and didn’t adequately appreciate that fact at the time. I was lucky to grow up in the 1960s and come of age in the 1970s, when anyone who was willing to go to yard sales and estate sales could buy huge numbers of books for next to nothing. Then they could turn those books around and sell them at their own yard sales and garage sales or sell them to used bookstores or use them as fodder for their own used bookstores.

There are some great used bookstores around, notably Powell’s, the Portland, Oregon-based seller of new and used books. Powell’s boasts of having more than a million books at its city-block-sized flagship location. I haven’t been there in years, but I don’t doubt the veracity of the boast. Powell’s is a thing unto itself among used books.

Pulp fiction and more

My favorite store of all the others besides Powell’s was a used bookstore in my hometown of Muncie, Indiana, Al Maynard’s Used Book Headquarters. It was located on the second floor of a deteriorating downtown building and was the kind of inaccessible place that wouldn’t be allowed now, and rightly so. The bookstore was at the top of a long flight of stairs and Maynard, who was famed for being cantankerous, had posted a hand-lettered sign at the top of the stairs. It read something like, “There are 23 steps behind you. Shoplifters will miss most of them on the way down.”

Maynard had accumulated a wealth of books that, in my mind, was a midwestern version of the Library of Alexandria: the wooden shelves lining all the walls were filled with hardbacks, paperbacks, scholarly works, old magazines – probably every edition of National Geographic – and pulp magazines from the first half of the 20th century.

The pulp magazines themselves were astounding. Their very name testifies to their brief time in the world, as they were printed on the cheapest and roughest paper available at the time, to maximize profits for their publishers. That these pulps – row after row, shelf after shelf – had survived decades after they were produced was extraordinary.

The building where Maynard’s bookstore resided was sold in 1982 and rather than find another location, he got out of the used books business and retired. Many of the pulps ended up in the private library of a friend from the time. They’re no doubt slowly decomposing in a room of his house. I can only imagine the smell of that much old pulp paper.

Just as smells of your mother’s cooking are an important part of memory and nostalgia, smell is a big part of longing for a proper used bookstore.

I mentioned on Twitter I was writing about used bookstores and some of my fellow writers weighed in.

“On my travels, every time I come across one, I’m compelled to go in,” M.E. Proctor said. “It’s the smell that seduces me. Like incense. Which makes sense, bookstores are my churches.”

Paperback writer – er, reader

Pulps aside, the staple of a good used bookstore is the paperback book. Encyclopedia.com says the first paperback was published in 1841 but paperbacks probably reached a zenith beginning a century later.

In Richard Lupoff’s 2001 history, “The Great American Paperback: An Illustrated Tribute to the Legends of the Book,” the era of modern U.S. paperbacks began with Pocket Books in 1939. In a review of Lupoff’s book, Paul Maliszewski wrote, “Why did Pocket and others succeed where their predecessors had failed? According to John Tebbel’s magnificent four-volume ‘History of Book Publishing in the United States (1972–81),’ Pocket combined the advantages of uniform size and price with enticing color covers, inexpensive paper, rotary printing (the technology first used to print newspapers on continuous rolls of paper), and—this is the key—a distribution system that treated books like magazines. Pocket allied with newspaper and periodical wholesale outfits, which placed the new paperbacks in drugstores, smoke shops, five-and-dimes, newsstands, train stations, and, of course, bookstores. No longer, the company promised, would readers be forced to ‘dawdle idly in reception rooms, fret on train or bus rides, sit vacantly at a restaurant table.’”

Paperbacks were inexpensive compared to hardcovers and held a mystique that could inspire a Beatles song. The paperback market thrived on mysteries and double-sided sci-fi and cheap versions of hardcover bestsellers, sometimes expurgated and sometimes not. Some publishers proclaimed on the cover: “CONTAINS EVERY WORD OF THE HARDCOVER ORIGINAL.”

For those reasons and others paperbacks were a blessing to used bookstores. These cheap books were really cheap to buy used from cardboard boxes at tag sales and they stuffed shelves at used bookstores. They were easy to take in trade.

And the rows of used paperbacks were the best way to search for a forgotten gem or previously unknown gem.

Or sneaky publications from the hottest author in the world.

At some point in the early 1980s, word started circulating – don’t ask me how, since this was before the Internet, but I heard these rumors – that Stephen King, my favorite author, was releasing books under a pen name.

What the name was we didn’t yet know, but the story was that King’s publishers thought his output was so prodigious that it would seem cheapened if he released more than one book each year.

Being a King fanatic – I’ve read “The Stand” more times than any other book – I immediately began searching my town’s used bookstores for paperbacks that might have secretly been penned by King.

How did I do this? Badly, it turned out. I looked for paperbacks that were horror or science fiction and whose author was unfamiliar to me. It helped if they were thick and gory.

I “discovered” that Robert McCammon was the pen name of Stephen King.

And I cleaned out my used bookstores of every McCammon book.

Of course, McCammon was not the pen name for Stephen King. King revealed in 1985 that he had published five books since 1977 under the pen name Richard Bachman.

I probably wasn’t the only person who thought some author was a King-created literary machine. I probably wasn’t the only person who thought that McCammon was King’s alter ego.

The winner in this incident was, no doubt, used bookstores, which sold a lot of books written by other authors besides King. Which is a good thing.

To live in the village of books

“I used to go to used bookstores to treasure hunt for old copies of Mary Stewart and Victoria Holt novels because I loved the books and the old covers,” my friend and author Meghan Leigh Paulk said. “Once everything became available on eBay, it just wasn’t the same.”

There are plenty of online resources now if you’re looking for particular books. A friend in Indiana recently came into possession of three dozen boxes of old paperbacks. They’re selling them online, I think, but I can’t help but fantasize about walking into a used bookstore and finding all those mid-century crime novels about hardboiled detectives and mysterious murders on the shelves.

Author Jozzie Stuchell Velesig agreed about the allure of a used bookstore. “When I was probably 14-ish, my mom dropped me off in a used bookstore while she ran next door to a different shop. She came back to find me in a corner on the floor completely surrounded by open books. It’s one of my happiest memories.”

Maybe a bunch of us should pack up and move to Hobart, New York, a town in the Catskills known as “The Book Village.” That’s because there are (at least) eight used bookstores there, lining the quiet streets of this town of fewer than 400 souls. (Surely someone will write a cozy mystery set in this town, featuring a bookstore owner killed by a rival … or rivals.)

Closer to home for me, I’ve been able to look around Knoxville a bit since we moved down here and have found lowercase books, a small used bookstore with a diverse collection of volumes including a Shakespeare set dating to the late 1890s, hardboiled detective novels like Mickey Spillane’s “The Big Kill,” his Mike Hammer novel from 1951, and several volumes of collected Pogo comics, many of which are already on our shelves at home.

Thanks to all the old books, the place smells right.

I know that I’m not just looking for a good used bookstore. I’m also looking to recreate how I felt when I was standing in one of those stores all those years ago.

I’d give a lot to be back in a cramped hole-in-the-wall store, running my fingers along the spines of those colorful paperbacks and picking up the scent of cheap, aging paper.

Those books would smell like the past. My past.