“I’m not involved… It had been an article of my creed,” Thomas Fowler boasts in The Quiet American, Graham Greene’s magnificent novel of Western embroilment in 1950s Vietnam. Not involved, Fowler insists, in the Indochina conflict; not involved in the murder of young CIA officer Alden Pyle, his romantic rival and sometime friend; not even particularly involved in his own two primary relationships—with wife and mistress. Fowler, a seasoned British journalist stationed in Saigon, takes pride in his neutrality, the only sensible position in a world of imperfect options: the Vietminh, French colonists, Americans, communists, Caodaists, Hoa-Haos. “The human condition being what it was,” Fowler intones, “let them fight, let them love, let them murder, I would not be involved.” The Quiet American, one might say, is the quintessential cautionary tale against entanglement.

I began to understand Fowler’s creed when I became a spy. In 2004, I volunteered to go to Baghdad as a counterterrorist case officer for the CIA. My mission was to recruit informants who could help track down Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQIZ) leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and dismantle his network. It was my first tour, a plunge into the murk of espionage and the knot of American involvement abroad. Terrorists were battling civilians; Shia were battling Sunni; everyone, it seemed, was battling America and its allies; even Iran had entered the fray. A complex landscape; one might call it, as Greene called Vietnam, a world of too many views.

On dusty, foreign soil, we struggled to identify a well-hidden and poorly defined enemy; to pick terrorists from mere troublemakers, empty threats from real ones, altruistic from ulterior motives, truth from lies. The stakes were high. Soldiers relied—and their lives depended—on intelligence we collected: a bomb location, a porous checkpoint, the name of a dealer peddling explosives. The battlefield had no clear lines. I became acutely aware of the possibility of missteps, of the precariousness, weight, and dangers of involvement.

Seven years after leaving Iraq, no longer a spy, I again landed in the Middle East. This time, in Bahrain, a tiny Persian Gulf island, during the Arab Spring. The Shiite majority was revolting against the Sunni monarchy, demanding rights, equality, opportunity. Saudi Arabia was backing the Bahraini regime, while Iran was rumored to be covertly assisting the opposition. America, whose Fifth Fleet is headquartered in Bahrain, was floating uncomfortably in the middle, torn between its own security needs, supporting democratic reforms, and fending off Iranian aggression in the Gulf. Once again, I was in a world, like Greene’s 1950s Vietnam, with many views and players—none angelic, none on clear moral high ground. Another thorny tangle that seemed to dare outsiders to get involved: Just try to pick a side.

My years in the Middle East made plain the challenges of American and foreign involvement. The region is still volatile, still hasn’t embraced democracy; conflict has persisted and even flourished in places. I found myself thinking back to The Quiet American. According to writer Robert Stone, Greene viewed Western involvement in Vietnam as “the beginning of a terrible mistake, a deadly mistake, the mistake of a great power armed to the teeth attempting to inflict its will in a part of the world to whose language and gestures it was tone deaf.” One could be forgiven for thinking Greene was opining on the here-and-now. It’s as though history and Greene are exchanging knowing glances.

Not long after leaving Bahrain, I opened my computer and began writing my first novel, The Peacock and the Sparrow. It’s about an aging, apathetic spy stationed in Bahrain for his final tour. Buffeted by the crosswinds of the Arab Spring, he becomes entangled in murder, consuming love, and an unpredictable revolution. Ultimately, he sheds his indifference and chooses sides—only to face the startling consequences of his decisions. More than half a century after The Quiet American was written, I found a well of inspiration in Greene’s wisdom.

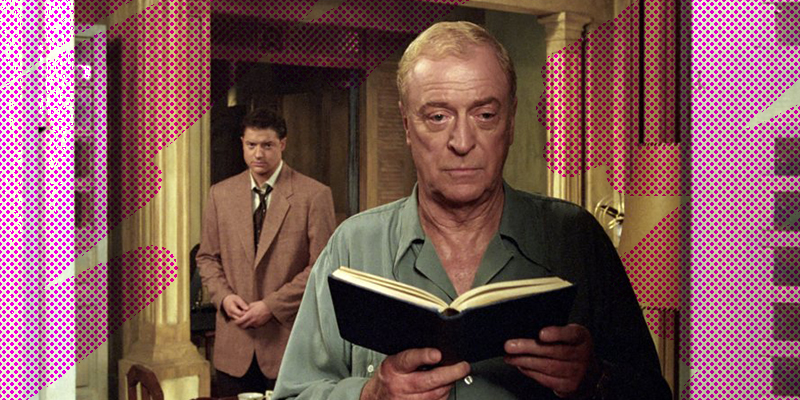

While writing, I also came to appreciate what is, perhaps, Greene’s most important message: that the human and global are hopelessly intertwined. That there’s little boundary between our inner and outer worlds. Conflict boils down to the personal stakes of our lives. In The Quiet American, Pyle’s crusade to save Vietnam blurs into his crusade to save Fowler’s mistress. And to Fowler, Pyle’s arrogance in foreign policy and his arrogance in his romantic ambitions are one and the same. Even the characters’ physicality reflects larger dynamics: Pyle, with his crew-cut and “wide campus gaze,” is the face of American optimism and naivete (Brendan Fraser’s doe eyes and smooth-faced schoolboy charm, in the 2002 film adaptation, have a similar effect), while fermented, fifty-something Fowler’s opium addiction, drinking, and weary movements betray, by his own admission, “age and despair.”

Entanglement can be hazardous. At its heart, it’s personal. Perhaps, then, Greene’s final message is no surprise: involvement is inevitable. It’s simply not possible to stay out of the fray, he seems to say. Neutrality’s an illusion. The ropes are no barrier to the ring. Eventually, a toe-dip or graze becomes submersion. The protagonist in my novel, Shane Collins, is tasked with uncovering Iranian support for the revolution against the Sunni monarchy. Along the way, he discovers his informant has murky allegiances; his ambitious station chief supports the regime at seemingly any cost; his lover, straddling the worlds of East and West, harbors her own secrets. Collins’ life and the Arab Spring twine until they’re indistinguishable. Little by little, he becomes involved. When, at last, Collins’ informant asks if he will do something for the revolution, Collins responds, “Which is it: for you or the revolution?” His informant replies, “Is there a difference?”

“Pyle believed in being involved,” Fowler summarily explains the young optimist’s demise. And by the end, Fowler too is involved. When Pyle, with his signature American arrogance, poaches Fowler’s lover, it’s simply too much for Fowler to bear; the Vietnam War has become personal. He resigns himself to his informant Heng’s adage that, “Sooner or later…one has to take sides. If one is to remain human.”

I often say that my novel is about the power and perils of belief. The simultaneous exhilaration and risk of doing something. “My downfall was also my salvation,” Collins reassures himself during his final, daring mission in The Peacock and the Sparrow. Stepping off the sidelines can be hazardous, but it’s also tempting, perhaps irresistible—as tempting as a river, a breeze, a pipe of opium, or the touch of a girl who might tell you she loves you.

***