All my life, I’ve loved folklore and mythology, and the way they fire the imagination. They aren’t history, but they suggest history and inspire us to think about the world as it existed before the one we know today. In a way, I feel the same way about my love of early cinema—it’s not the way the world really was, but a window through which to view the storytellers of a world long past.

I’ve always had a particular fascination with horror tropes and legendary monsters, as part of this larger interest in the stories of the past. My first novel, Of Saints and Shadows, was largely inspired by my thoughts about vampire folklore, about the “rules” of vampire stories. In that novel, I tried to create my own mythology to make sense of it all, but in other works I’ve focused on the idea that every one of these monstrous legends must have a root. There were vampiric legends all over the world at a time when stories didn’t travel much, which brought me to the conclusion that there had to be some other reason for the similarities in the folklore of these far-flung places.

In the many years since then, I’ve dug into—and invented—both history and pre-history many times. I love imagining a world before the world, before humanity. Gods before gods. Monsters who lived so long ago that historians can’t say for sure whether or not they existed. The Earth is very old, and we continue to be surprised by discoveries of evidence of human societies in places and times we once thought impossible.

This isn’t to say that I believe monsters roamed the Earth in pre-history, but it’s so much fun to imagine, and every time there’s a new discovery about pre-history, story sparks fly. When I wrote my Bram Stoker Award-winning novel Ararat, I certainly didn’t believe that Noah’s Ark existed, but I knew that stories of an incredible flood were common across a variety of ancient world cultures, which suggests that such a flood really happened. To the people in those times, it must have seemed as if the whole world flooded, because they didn’t realize how much more “world” was out there. The real stumbling block was figuring out how anyone could have built an “ark” in a time when boats had barely been imagined, and methods had not been created to craft a boat of that size that could have stayed afloat.

In my novel Road of Bones…hmm, how do I explain this without spoiling it for you? Suffice to say that as the story unfolds, we learn about the world before the world. There are layers of supernatural in that book—one that represents human society, one of early human history, and a layer that I suppose we could call the world before the world before the world. A time when the spirits of nature roamed, unfiltered, unchained by human concepts of good and evil. The arrival of the first people gave them something to pique their interest, and the adoration or fear they inspired in those first people turned them into something else. Gods and monsters and devils.

When Mike Mignola and I wrote our novel Baltimore, or the Steadfast Tin Soldier and the Vampire, we found a shared love of such stories, of folklore, and imagining a world that was ancient when the ancients were young. As Baltimore’s story segued into comic books, building through that and other titles in its own comic book universe—the Outerverse—we crafted a massive, sprawling pre-history, including a creature called the Red King, who in the Outerverse was the father of all monsters. In the pages of Baltimore and then Lady Baltimore, we continued to explore, and when we introduced a variety of witches into the series, my instinct demanded that I explain that variety. Who were these witches?

The Ur-Witch was born.

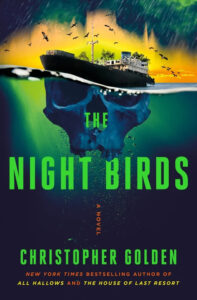

Though the world of The Night Birds is very much not the same world as the Outerverse, I’ve borrowed the concept of Ur-Witches from myself, and it has evolved significantly. There are so many different ideas and images of witches and witchcraft, around the world and across the centuries. Some of those images are empowering and others were created as tools of oppression. Some conjured beauty and others ugliness. But, as with vampires, the legends and stories of people (especially women) and creatures who were portrayed as witches, or as performing something like witchcraft, span the world. So when I sat down to write The Night Birds, I wasn’t just thinking about a coven of witches, I was thinking about the roots of that coven. The history and folklore.

These weren’t going to be modern wiccans, or stereotypes from the Middle Ages. These are contemporary women who discovered the ancestral roots of witchcraft, going back to the earliest humans. In this story, I delve into the prehistoric existence of a race of creatures capable of monstrous magic, the Ur-Witches—the beings that inspired thousands of years of legends around the world, and a profound dread in small men who were afraid of powerful women. These Ur-Witches were worshipped by women who learned their craft and were gifted with a bit of their magic. The remaining legends come down to us from Iceland, where these women were called NäturvefjarI. In English they’re “the night weavers,” and they are the reason for our ancestral fear of witches and conjurors, and the terrifying imagery that lingers in our reptilian brains and imprints itself on human perceptions over the centuries.

The thing that makes me happiest about this bit of folklore is when readers come up to me and ask about my research into Icelandic folklore, and I get to tell them it’s all invented. There are no legends of the Ur-Witches or the Näturvefjar outside of this novel, but it thrills me to think that readers might go on believing this folklore is real, because then…doesn’t it become real? Doesn’t it become part of the existing folklore? Centuries from now, if some student or historian believes that ancient people worshipped Ur-Witches and thought of themselves as Näturvefjar, nothing would make me happier.

It all starts in The Night Birds.

***