Deception is elemental to a good mystery. The author misleads the reader constantly, from every angle.

The characters mislead each other.

Or they mislead the reader, or both.

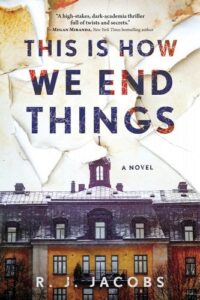

Lying is a theme in my new novel, This Is How We End Things, which is set in a psychology department at a small university where ethically questionable research is being conducted. Psychology is infamous for manipulating perceptions—a mirror may actually conceal an observation room, the participants might not be who they say they are, or the purpose of the study isn’t what’s been advertised—and the history of psychology is filled with research that wouldn’t be possible in the current era because of increased awareness of their potential to harm its participants. It’s an interesting paradox that insights provided by those early studies were essential to moving the field forward and increasing scientific understanding of human nature.

So, when is it ethical, to paraphrase the quote from Merchant of Venice, for characters to do a great right, by doing a little wrong? Characters in modern mysteries and thrillers are most effective when they’re relatable.

When are their deceptions justified?

There are two main ways that lying is seen as justifiable:

1. A character deceives others about their background or identity in order to pursue a virtuous end (they’re under cover).

- Without delving too far into spoiler territory, a character in my new novel, The Is How We End Things, deceives the others about their past. They justifiy this deception because the work they’re doing at the university is meaningful, their long-term career path has the capacity to help many others, and they’d be prevented from pursuing it if their true background was known.

- The Last Flight, by Julie Clark. The main character, Claire, has been planning to flee her abusive marriage for months. When she meets a woman who’s circumstances are equally dire, they switch identities in order to escape. Neither is who they say they are afterward, but they’ve deceived the others in the pursuit of safety and justice.

- What Have We Done, by Alex Finlay. Jenna was trained as an assassin as a teen but has left that life behind to build a stable family life. It’s an adaptive change if ever there was one, and since she was recruited as a young person, her deception is warranted so she can live a productive adult life.

- The Clinic, by Cate Quinn. The main character, Meg, works for a casino in LA, catching cheaters until her sister is found dead in a rehab facility. Meg can’t believe rumors of suicide, and decides to check herself in to the same facility to investigate from the inside. She’s deceiving the others about her identity, but has the chance to catch a murderer.

2. A character deceives others about something they know in order to protect them or pursue a virtuous outcome.

- Murder on The Orient Express, by Agatha Christie. Perhaps the quintessential example of justifiable deception, the characters know what one among them has done but can’t openly share their motives to kill. The real killer must pay.

- No Exit, by Taylor Adams. In a critical sequence, the main character, Darby, must deceive the others into thinking that she does not know about the kidnapped girl in the parking lot. She’s sure one of the others is the kidnapper and revealing the situation too soon would put everyone, particularly the young girl, in greater danger.

- Before She Knew Him, by Peter Swanson. When the main character, Hen, begins to suspect that a new acquaintance is responsible for a student’s murder the previous year, she begins following him. Knowing she would be doubted, and even suspicious of her own perceptions, she conceals her suspicions until she can gather sufficient evidence. Without her concealment, a killer could more likely evade capture.

- Survive the Night, by Riley Sager. The main character, Charlie, is offered a ride home by a man she suspects to be a notorious campus killer. She hides her suspicions from him and hatches a plan to exact revenge and ensure he won’t kill again.

In general, lying is usually seen as ethical to people who are emotionally fragile, near death, or who’s circumstances would be made worse by the truth. In many mysteries and thrillers, a main character is unreliable, which is a playful form of deceiving readers. In these instances, the characters are often seen as sympathetic because they’ve been deceiving themselves all along. Planting a red herring is also a lie of sorts, but imagine a mystery novel in which everything was exactly as it seemed. No guesswork would be required, but most readers would probably agree the story would be a lot less fun.

***