In the 1970s, I was a few years out of high school with dreams of being a writer when, in Toronto, to see a friend, I had time on my hands.

The author, Morley Callaghan, lived there. I stopped at a public phone and looked him up in the phone book – remember those? I loved his work. I found his short story, “A Cap for Steve,” very moving. Callaghan was celebrated and had been nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. I knew from reading Callaghan’s memoir, That Summer in Paris, that he’d been friends with the likes of James Joyce, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. Callaghan’s summer in Paris was in the late 1920s. At the time, Fitzgerald was working on Tender Is the Night and Hemingway was wrapping up A Farewell to Arms.

In Paris, Callaghan and Hemingway often boxed at the American Club. One day Fitzgerald joined them as timekeeper. But Fitzgerald let the time of one round slip by, allowing Callaghan to knock Hemingway down. Fitzgerald’s mistake infuriated Hemingway. “All right Scott, if you want to see me getting the shit knocked out of me, just say so. Only don’t say you made a mistake,” Callaghan remembered Hemingway saying to an apologetic Fitzgerald, in the incident which became literary lore.

Standing at the phone booth, I found Callaghan was listed.

I called. I was nervous. I didn’t know Callaghan. What was I doing? I was ready to hang up when a man answered: “Hello.”

“Is this Morley Callaghan?”

“Yes.”

“The author?”

“Yes.”

“I just want to say I enjoy your work, sir.”

There was a pause and he cleared his throat.

“Thank you, I feel ennobled.”

That was it. I walked away having just talked to an ascended god of literature. Very cool, I thought, leaving happy, and kick-starting my amateur pursuit of literary titans. Over the years I’d sat on Hemingway’s bed in Key West, visited the London homes of Joseph Conrad and Charles Dickens, where I sat alone at the writing desk used by Dickens. I visited the dorm of Stephen Crane in Syracuse, and the building where Fitzgerald died in Hollywood.

It got me thinking about how interesting it must’ve been when literary legends met.

Like the time Charles Dickens met Victor Hugo in Paris.

According to a blog post by literary editor, Levi Stahl, who cites two biographies, Charles Dickens a Life by Claire Tomalin, and The Life of Charles Dickens, by John Forster, the year was 1846. Dickens, 34, traveled to Paris with his friend, Forster. The pair called on Victor Hugo, who was a star at the time, having published, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame and was setting out on the years-long struggle that would be Les Misérables.

Stahl writes how Hugo impressed them with his “eloquence, and, very charming flattery, in the best taste.” For his part, Dickens said that Hugo, “looked like the Genius he was, while his wife looked as if she might poison his breakfast any morning.”

If we move ahead a few years, and across the Atlantic, we come to what I regard as something of a gem. It was December 31, 1867, Charles Dickens, at the height of his fame, was reading from David Copperfield at Steinway Hall in New York City. What transpired is drawn from The Mark Twain Papers, Autobiography of Mark Twain, and Listening To Charles Dickens Read David Copperfield With His Future Wife, by Matt Seybold at the Center For Mark Twain Studies; and “How the Great Do Tumble:” Mark Twain’s Later Articles in the San Francisco Daily Alta California, by Andrew Jewell at the University of Nebraska.

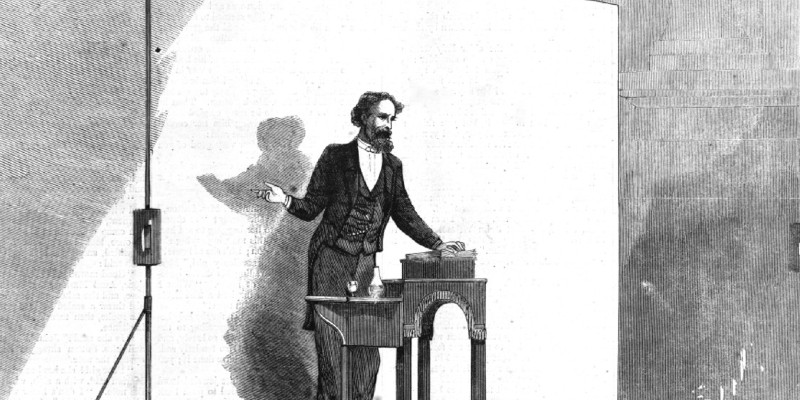

As you may have guessed, in attendance was Samuel Clemens, otherwise known as Mark Twain, then a correspondent who reported on the appearance of Dickens for a San Francisco newspaper. He described the set.

“Dickens stood in front of a huge red screen … Mr. Dickens had a table to put his book on and on it he also had a tumbler, a fancy decanter and a small bouquet. Behind him he had a huge red screen – a bulkhead – a sounding board, I took it to be – and overhead in front was suspended a long board which threw down a glory upon the gentleman, after the fashion in use in the picture-galleries for bringing out the best effects of great paintings. Style! – There is style about Dickens, and style about all his surroundings.”

But, as Matt Seybold writes, Twain considered Dickens a bad reader because he “did not cut the syllables cleanly.” His “husky voice” and “monotonous” delivery didn’t do justice to “the beautiful pathos of his language.” Still, Twain, “the aspiring novelist,” was a fan of the legend before him, admiring “that queer old head” with “the wonderful mechanisms within it,” Seybold writes.

Some twenty years later, in 1888, Twain’s fame clearly established, he met with Scottish author, Robert Louis Stevenson, who gave the world, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; Treasure Island, and Kidnapped.

According to The Mark Twain Papers, Autobiography of Mark Twain, Twain admired RLS’s work and was pleased when RLS said he had read Huckleberry Finn “four times, and am quite ready to begin again tomorrow.” Stevenson, ill with lung disease, had wintered in a health resort in Saranac Lake, New York and wrote to Twain proposing they meet when he got to New York City.

“It was on a bench in Washington Square that I saw the most of Louis Stevenson. It was an outing that lasted an hour or more and was very pleasant and sociable,” Twain wrote, according to The Mark Twain Papers, Autobiography of Mark Twain.

“I had come with him from his house where I have been paying my respects to his family. His business in the Square was to absorb the sunshine. He was most scantily furnished with flesh. His clothes seem to fall into hollows, as if there might be nothing inside, but the frame for a sculptor statue.

“His long face and lank hair and dark complexion, and musing and melancholy expression seemed to fit these details, justly and harmoniously, and the altogether of it seemed especially planned to gather the rays of your observation, and focalize them upon Stevenson’s special distinction and commanding feature, his splendid eyes.

“They burned with a smouldering rich fire under the penthouse of his brows, and they made him beautiful.”

Looking at other relationships, one of the most interesting, as most literary historians know, is the friendship between Joseph Conrad and Stephen Crane.

It comes to life in the recent and excellent work, Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane, by Paul Auster, from which I borrow.

Crane was famous for The Red Badge of Courage, when he traveled to England. There, an editor, who worked with Crane, 26, and Conrad, 39, arranged for the two to meet in a London restaurant, October 15, 1897. Auster notes Conrad’s recollection.

“We shook hands with intense gravity and a direct stare at each other, after the manner of two children told to make friends.” When they talked, Conrad said, “I like your General,” referring to a character in The Red Badge of Courage. Crane responded, “I like your young man – I can just see him,” referring to one of Conrad’s characters. They talked for hours, walking London’s streets, and their friendship was born.

Auster writes that the Cranes rented Ravensbrook Villa in Surrey, socialized with authors like Henry James and Ford Maddox Ford. But it was Conrad and his family, whom they invited to stay with them for ten days at Ravensbrook in 1898. It may have arisen from his background as a reporter, and being poor and sharing tenement apartments with friends, but Crane was known to be able to write in a noisy room without being distracted.

Auster writes that during their stay, Conrad and Crane were so comfortable with each other that Conrad would sit in Crane’s study with him while Crane worked, noting Conrad’s memory of it.

“Crane would settle himself at the long table, at which he used to write. I would take a book and settle myself at the other end of the same table, with my back to him; and for two hours or so not a sound would be heard in that room. At the end of that time Crane would say suddenly: ‘I can’t do anymore now, Joseph’. He would’ve covered three of his large sheets with regular, legible, perfectly controlled handwriting, with no more than half a dozen erasures – mostly single words in the whole lot. It seems to me always a perfect miracle in the way of mastery over material and expression.”

Later, Auster reports, that before their relationship took a complicated turn, Crane, in a letter to a friend, praised Conrad and his skill, writing of Conrad: “He is strangely hopeless about himself. I like him …. His eye is very individual and his expression satisfies me artistically … why is he not immensely popular? With his strength, with his rapidity of action, with that amazing faculty of vision – why is he not?”

When it comes to complications, action and braggadocio, you can look at the time John Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingway got together, the one and only time the two authors met. It was 1939, at Costello’s New York Bar and Restaurant on 3rd Avenue. Steinbeck, a rising star after Grapes of Wrath, and his friend writer John O’Hara met Hemingway, as chronicled and taken from, John Steinbeck and His Contemporaries edited by Stephen K. George and Barbara A. Heavilin.

Steinbeck, after reading one of Hemingway stories, “The Butterfly and the Tank,” in Esquire, wrote to him, and said the story struck him as, “One of the finest stories in all time.”

According to George and Heavilin’s book, Hemingway told a friend about Steinbeck’s letter. That friend set up a dinner for Steinbeck and Hemingway at Costello’s. Meanwhile, novelist John O’Hara was there at the bar and had a walking stick that Steinbeck had given to him as a gift. Hemingway noticed the stick, questioned its composition and bet O’Hara $50 that he could break it over his own head. O’Hara took the bet and Hemingway broke it over his own skull.

“It was no great achievement because the cane was old – that was part of its value in Steinbeck’s eyes, but Hemingway was very proud of himself. Steinbeck was silently disgusted. As much as he admired Hemingway’s writing he scorned Hemingway’s search for publicity, and the legend it fostered,” according to the text edited by George and Heavilin.

Of course, the history of literature is coloured with many encounters, friendships and feuds. Often, they make for reading as compelling as the works themselves.

As a midlist author, I’ve had the privilege of meeting many of my contemporaries, at all levels in their careers. I’m pleased to report that no punches or shade, have been thrown, no challenges issued, and no breaking of anything.

So far.

***