In crime novels, the most famous narrator is probably the private eye. As Raymond Chandler famously described it: “down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero; he is everything.” Through this single perspective, the reader learns about the world and the people in it; the narrator is our arbiter of good and bad, lies and truth; they both seek and often define justice.

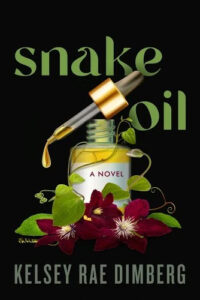

When I was writing my second novel, Snake Oil, I wanted to do the opposite. Instead of a private eye hero who’s “everything” to the story, I wanted to embrace ambiguity, to throw open the questions of good and bad, right and wrong. Snake Oil centers on Rhoda West, a charismatic founder-CEO who’s been accused of some pretty bad deeds. But is she really a villain? In real life, the question would be decided on the internet, probably without much nuance. In my book, I used multiple narrators—a believer, a skeptic, and Rhoda herself—to tell their version of the story. The position of “hero” is uncertain, and even changeable.

Multiple perspectives dramatically impact the structure, pacing, and even meaning of a story. Here are some of my favorite crime novels that deploy multiple narrators to brilliant effect.

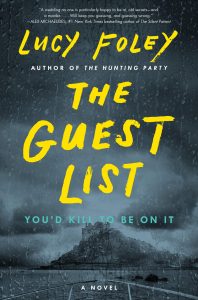

The Guest List by Lucy Foley

Lucy Foley’s mystery novels leap from narrator to narrator in fast-paced chapters, like racers handing off the baton in a relay. In The Guest List, her five narrators convene on a remote island off the coast of Ireland, each as marooned in their own minds as if surrounded by an ocean of rough chop, an emotional riptide. “Everyone has a secret,” the book jacket teases, so the reading experience is quite different from a traditional detective story. Instead of a narrator walking us through the process of deduction, the reader becomes the sleuth. With every chapter, our theories shift. The question is less who-dun-it and more who didn’t do it?

Foley sets up the puzzle early. After a prologue promising murder on the night of a big wedding, we turn back in time to meet the future bride trying on her dress. Ruminating on an anonymous note warning her about the groom, she rationalizes that her whirlwind romance isn’t a mistake: it’s proof of true love. In the next chapter, the best man casually muses that the groom is after the bride’s family money. And so it goes, each chapter’s point of view swiftly undermined or re-framed by information in the following chapter. The imbalance of knowledge generates lots of suspense. After the best man learns of the groom’s betrayal, or the bride’s sister reveals the identity of her dastardly ex-lover, the reader turns the page to find herself inside the mind of a character who doesn’t know what we know—and watch as they wander into danger.

This device does more than complicate the plot. The real question of the book is whether one person can ever truly know another. Readers are privy to the envy between sisters, the raw grief of a seemingly unimportant plus-one, and the haunted nightmares of the best man, so we understand their actions in a way that the other characters cannot. As the bride walks down the aisle, she thinks, “For a strange moment I have the feeling that our guests are all strangers…including the man waiting for me at the end.” She may be right about her husband, but the relationship the reader hopes can finally find words is the one between Jules and her unhappy sister.

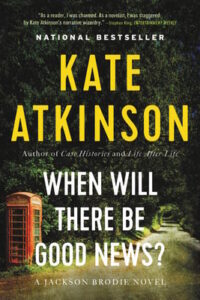

The Jackson Brodie Series, Kate Atkinson

If you’re looking for a series that openly plays with the notion of private eye as hero, look no further than the delightful, hilarious, and devastating novels of Kate Atkinson’s crime series that begins with Case Histories. The series is nominally centered on a private eye who, at a glance, seems to fit Chandler’s definition. Policeman-turned-private-detective Jackson Brodie is solitary and scarred, with a haunted past, a troubled losing streak with women, and a moral code that doesn’t always equate justice with the law. Jackson is fiercely devoted to solving his cases, so stubbornly loyal several characters compare him to a German shepherd. True to genre, Jackson diligently pursues suspects and clues, but here the comparison stops. Jackson is continually perplexed. In When Will There Be Good News?, for instance, the detective spends much of the story driving aimlessly around the countryside, only to board a train going the wrong direction, a very literal way to show how peripheral his sleuthing is to the story.

Though the books do set up (and solve) mysteries, coincidence is more relevant than procedure. The numerous narrators intersect in surprising ways, colliding like billiard balls and sending the story (and Jackson) spinning in new directions. By decentering the methodical accumulation of clues toward a solution, Atkinson toys with the notion of closure as a possibility. Many of her narrators—including Jackson—are the family or friends of crime victims, whose lives have carried on, yes: but so have their scars. “Really, you’re looking for your sister,” one character tells Jackson. “Your own dear grail. You’re never going to find her, Jackson. She’s gone. She’s never coming back.”

The God of the Woods, Liz Moore

Multiple perspectives give us a bigger window on a story than any single narrator can. In The God of the Woods, the narrators are locals and summer people, of different ages and social classes. One narrator is an investigator on the missing person case at the heart of the book, another is arrested as a suspect. These voices draw a rich picture of the setting. Everything matters, from the gossip at sleepover camp to the risqué parties of the nearby mansion, the protocols and prejudice of the police force, and even the economics and history of the region.

Moore has another trick up her sleeve. In addition to multiple narrators, she tosses in multiple timelines. The character of Alice Van Laar narrates both in the present day of the story, 1975, and in the 1950’s and 60’s. In 1975, where we first meet Alice, she’s rather…odd. Cold and harsh to her daughter, she’s also in pain herself. Glancing at the clock, she thinks, “Her daily countdown was underway: at five o’clock, she was allowed one of the pills Dr. Lewis had prescribed for her nerves.” Instead of the recommended one pill, she swallows two. She has “bad days,” we learn, when “she was thinking too much about Bear.”

Alice is the mother of a young boy who mysteriously vanished several summers earlier—and in 1975, her daughter disappears as well. Flashing back to the chapters narrated by a younger, loving, shy Alice, the reader wonders what happened to the missing children—and to Alice. Her transformation is like a second mystery, running under the story like a current in a river, and we sense that whatever happened to change Alice must be key to the disappearances.

Laura, Vera Caspary

Using multiple narrators in a crime novel isn’t new. Back in 1943, Vera Caspary puzzled over a limitation of crime fiction: “The murderer,” she wrote, “the most interesting character, has always to be on the periphery of action lest he give away the secret that can be revealed only in the final pages.”

The solution? Write a novel with multiple narrators. In Laura, after a beautiful advertising executive is found killed in her apartment, the men in her life take it upon themselves to tell her story.

Up first, Laura’s friend Waldo Lydecker. A snobbish, elegant bachelor whose droll essays have made him wealthy, Waldo is happy to play narrator. The day after her death, he writes, “I had gathered strength for the writing of Laura’s epitaph. My grief at her sudden and violent death found consolation in the thought that my friend, had she lived to a ripe old age, would have passed into oblivion, whereas the violence of her passing and the genius of her admirer gave her a fair chance at immortality.”

How lucky for Laura! Yes, she’s dead, but now she’ll be brilliantly preserved by Waldo’s pen.

The narrative eventually shifts to the detective Mark McPherson, who is intrigued by the magnetic (albeit dead) Laura himself.

In Laura, the multiple perspectives are in competition. Who gets to tell Laura’s story? Who gets to possess the beautiful dead woman?

All this is complicated when (spoiler alert) midway through the novel, Laura walks into her own apartment, finding the detective napping over her diaries. The investigation spins in a new direction, with Laura herself the prime suspect.

When Laura finally gets her own narrative, she must overcome the obstacle of the reader’s already seeing her through the male narrators’ eyes. Their narratives are a bid for control, but Laura’s is a bid for agency—a struggle that fuels the story to its finale.

***