This week’s debut of The President Is Missing, by former president Bill Clinton and bestselling scribe James Patterson, marks the first time a “leader of the free world” has used his insider knowledge of the White House to concoct a thriller. But the fact that Clinton accepted this challenge should surprise no one. Like several of his predecessors, America’s 42nd chief executive is an avid crime-fiction reader. An invitation from Patterson to conspire in creating his own page-turner—one that envisions a courageous president ditching his security detail in order to combat a computer-virus threat and expose an advisor’s betrayal—must have been too enticing to ignore. Clinton and Patterson’s book joins an already packed sub-genre of political suspense novels featuring current presidents, future presidents, or their wives as the victims, perpetrators, or solvers of crimes. The dozen titles considered below, some of them built around genuine politicians, represent no more than a sampling of this field’s bounty.

Absolute Power by David Baldacci (1996)

During the 2016 presidential race, Republican Donald Trump—increasingly cocky about his followers’ loyalty—declared, “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose any voters.” But could an elected chief executive get away with murder? In his 1996 debut novel, Baldacci imagines an AARP-eligible burglar, Luther Whitney, breaking into a Virginia mansion—only to hide in the master bedroom as an inebriated male in his 40s and a blonde half his age suddenly stumble in for sexual escapades. When their dalliance turns rough, however, and the woman defends herself with a letter opener, two armed men burst in and blow her brains out. The drunk, it turns out, is Alan J. Richmond, president of the United States; the deceased is Christine Sullivan, the lady of the house. And Whitney? Well, he’s now witnessed a slaying that Richmond’s amoral chief of staff will do anything to cover up, be it rigging the crime scene to look like a fatal break-in or targeting Whitney (who was spotted fleeing the manor) for expeditious removal. Of course, Whitney’s no dummy: he has crucial evidence implicating Richmond in that night’s violence. Whether he’ll have time to employ it for his own survival and to bring down the sociopathic prez is another question altogether.

The Murder of Willie Lincoln by Brad Solomon (2017)

President Abraham Lincoln was devastated by the death of his third son, 11-year-old Willie, in February 1862. The boy took after his father in many respects, being amiable, curious, and possessed of a facility for language that came out in poetry. After Willie perished, reportedly of typhoid fever—which briefly also brought down his younger brother, Tad—the president was oft heard weeping, and social activities at the White House were curtailed for months. But could Willie have died of causes more nefarious than typhoid? That’s what John Hay, an amateur boxer, aspiring litterateur, and one of the president’s two young private secretaries, comes to suspect after receiving an anonymous missive suggesting homicide. At the president’s behest, Hay reconstructs the run-up to Willie’s illness, and seeks to determine whether anyone—be it White House staffers, Southern secessionists intent on striking at Lincoln through his son, or even the president’s own family—helped compel the boy’s untimely exit. A delightful re-creation of anxious and poisonous Civil War-era Washington.

The Impeachment of Abraham Lincoln by Stephen L. Carter (2012)

In this alternative construction of history, Lincoln doesn’t expire in April 1865 after being shot at Ford’s Theatre. Instead, he survives—but then must face, two years later, a potential sacking by radicals in his own Republican Party, who believe the post-Civil War South deserves much harsher treatment than this “petty tyrant” has inflicted upon it. (The congressional hearings to oust the 16th president are based, in part, on the 1868 impeachment and trial of his real-life successor, Andrew Johnson.) Beneath the courtroom drama, though, is layered a multifaceted, dynamic subplot involving the elimination of one of Lincoln’s attorneys (supposedly in company with a prostitute), and the investigation of said crime by 21-year-old Abigail Canner, a brilliant and ambitious African-American law clerk. Enhancing the mystery’s mix are coded messages hinting at a “conspiracy [that] reached the heights of the President’s closest friends and advisers,” and a packet of letters that might prove invaluable to the defense, but come from a suspect source. Ignoring instructions from the “sleepy but cunning” Lincoln to end her probing, Canner continues yanking at loose threads of political chicanery, until she discovers her connection to that scheming is closer than she realized.

The President Vanishes by Anonymous (1934)

Clinton and Patterson aren’t the first fictionists to play out the consequences of an Oval Office occupant disappearing. Robert J. Serling tested such a premise in The President’s Plane Is Missing (1967), and Michael Avallone tried it again in Missing! (1969). The granddaddy of them all, though, is The President Vanishes. That yarn gives us President Craig Stanley, who has been severely criticized for promoting pacifism, even as a disastrous war looms in Europe. Stanley’s failure to show up for his address to Congress on these matters is followed by news of his kidnapping. Suspicion falls on pro-war factions, including munitions companies and the fascistic “Grey Shirts.” Yet the Secret Service fears the roots of this crisis may be traceable to the West Wing, with every cabinet secretary a possible conspirator. As the search for Stanley continues, and riots occur nationwide, the rush to war quiets—which may be the best possible outcome. The President Vanishes was originally credited to “Anonymous,” but was later revealed as the work of Rex Stout, creator of series sleuth Nero Wolfe.

No Safe Place by Richard North Patterson (1998)

Kerry Kilcannon, a U.S. senator from New Jersey and the younger brother of another presidential hopeful gunned down in Patterson’s 1985 novel, Private Screening, is something of a dream candidate—mediagenic, idealistic, and refreshingly self-effacing, at least in private. He’s now launched his own campaign for the nation’s highest office, challenging a sitting (but altogether too slippery) vice president for the Democratic Party’s nomination, speaking out in favor of campaign-finance reform, gun safety, gay rights, and compulsory national service. His prospects look favorable, though it’s hardly smooth sailing to Election Day. The Kennedy-esque Kilcannon is haunted by his sibling’s assassination. Word of his past affair with Lara Costello, a comely Hispanic-American TV journalist, has leaked and could become a major scandal. And Kilcannon’s willingness to address the moral ambiguities of abortion has drawn fire from pro-choice supporters at the same time as it’s drawn the ire of anti-abortion zealots—especially a well-armed member of that set, who is stalking the candidate as he competes in California’s presidential primary. No Safe Place is much smarter than the average political thriller, filled with consultants, newsies, and powerbrokers whose behavior and observations would strike any veteran of American elections as familiar.

The Lunatic Fringe by William L. DeAndrea (1980)

Anyone who saw the TV mini-series based on Caleb Carr’s The Alienist knows that prior to becoming president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt served as president of the board of the New York City Police Commissioners. In that post, he made law-enforcement reforms and sought to turf out corrupt officers. DeAndrea’s novel, set in 1896, at the height of the city’s newspaper circulation war, presents Roosevelt with quite another challenge. The tale introduces policeman Dennis Patrick Francis-Xavier Muldoon, who—summoned by shrieks from a tenement landlady—breaks into an apartment and stumbles across a dead man in a wingback chair. He’s Evan Crandall, until recently an editorial cartoonist for William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. In the adjacent bedroom, our hero is shocked again, this time by a beautiful naked woman, tied up beside a painting of her full fair figure. Muldoon releases this “Pink Angel” and goes for assistance; but before he can return, the girl flees with both the cop’s gun and the canvas. Straightaway booted from the force for this bungling, Muldoon turns to Roosevelt for help. Together, they embark on a search for the wayward Angel as well as Crandall’s killers, one that will lead them to a band of burglars, anarchists bent on blowing up Croton Reservoir, and an assassination plot.

The First Lady by E.J. Gorman (1995)

If a president can take a life, why can’t a president’s wife? After three years in the White House, Claire Hutton is used to the demanding schedule and lack of privacy that come with her role as first lady. What’s harder is being neglected by her hubby, Matt, a moderate Republican chief exec who’s dogged by rumors of infidelities and faces political opposition from all fronts. Seeking succor, Claire turns to an old college pal, David Hart. That’s a big mistake, because he’s now a charming gigolo who threatens to give their association a salacious spin and peddle it to the press, unless she forks over $100,000. Worse, no sooner does Claire pay this blackmail, than Hart is murdered and a videotape surfaces to incriminate her. With right-wing radio commentator Knox Stansfield—a thoroughly odious and frustrated former suitor—drowning her in a drip-drip of innuendo, Claire must remake herself as Nancy Drew if she’s to salvage her reputation as well as Matt’s re-election prospects. This caricature of cutthroat politics comes complete with zippy storytelling, duplicity and disloyalty in spades, and even a cinematic car chase.

Jack 1939 by Francine Mathews (2012)

It’s early 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt is mulling a run for his third term in the White House, and John F. “Jack” Kennedy—the self-confident, philandering son of America’s wealthy ambassador to Great Britain—is just 21 years old and planning to cross the Atlantic to do research for his Harvard senior thesis (destined to become the 1940 bestseller Why England Slept). Yet Jack has already caught FDR’s eye. The wheelchair-bound head of state, concerned that German Chancellor Adolf Hitler wants to influence the 1940 U.S. presidential election and replace him with a political isolationist, recruits Kennedy as a personal spy to sort out what the Nazis are up to—and (ideally) stop them. But as Kennedy fine-tunes his espionage skills, he also enjoys a romantic liaison with a rather aloof Englishwoman (a fascist sympathizer he’s not sure can be trusted), and he is dogged by a lethal fanatic on the Gestapo payroll. Homicides ensue, bed sheets are given a proper rumpling, the Enigma cipher machine finds its way into the action, and author Mathews offers insights into vexatious relationships within the Kennedy clan.

The Only Thing to Fear by David Poyer (1995)

In the spring of 1945, with World War II winding down, now 27-year-old Navy lieutenant Jack Kennedy—recovering (with a bad back and mysterious fatigue symptoms) from dramatic action in the South Pacific—is transferred to Washington, D.C., where he joins FDR’s personal staff. It seems “someone close to the President is planning an attempt on his life,” and it falls to Kennedy to impede a Russian killer who’s defected to the Nazis and arrived in the U.S. capital via U-boat. The Germans hope Roosevelt can be slain in such a way that it implicates the Russians, splits the Allies, and provokes a military altercation between the United States and the Soviet Union that will take a bit of heat off the Third Reich. With aid from a comely actress and a modicum of sharp marksmanship, Kennedy just might be able to save the day. A farfetched but captivating adventure, nicely capturing the 1940s atmosphere and enriched by its depiction of two Democratic presidents—one then current, one future—joined by ideals and, in this case, subterfuge.

The Whole Truth by John Ehrlichman (1979)

Ehrlichman, who’d served as White House counsel to Richard Nixon, wound up doing 18 months in prison for his involvement in the Watergate scandal. He penned his debut novel, The Company (about a Machiavellian CIA director), before going to the slammer; he wrote most of The Whole Truth behind bars. The latter work pictures President Hugh Frankling being essentially bribed by a multinational corporation—one heavily involved in Latin America—to authorize a CIA operation to assassinate the leftist leader of Uruguay and replace him with somebody friendlier to U.S. interests. Predictably, this coup attempt ends in disaster. Frankling, worried that Congress’ investigation of the matter will lead to his impeachment, decides his optimal strategy is to deny everything, lie his ass off, and blame the whole fiasco on Robin Warren, the special aide he’d sent to give the CIA its marching orders. What results is a battle in the press between the president and his subordinate, both seeking to prove their own credibility and knock down their opponent’s. Eventually, Frankling is pushed to the edge of a Nixon-like resignation, but not before Ehrlichman fills his pages with sex, bipartisan skullduggery, and other crowd-pleasing diversions.

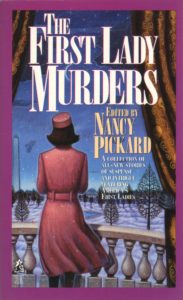

Mr. President, Private Eye edited by Martin H. Greenberg and Francis M. Nevins Jr. (1988) and The First Lady Murders edited by Nancy Pickard (1999)

If you still haven’t had your fill of intrigue linked to denizens of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, then track down these volumes of short stories. The first comprises a dozen original tales, each casting a U.S. president as mystery-solver. Edward D. Hoch, for instance, imagines a dying George Washington leaving behind evidence of treachery. . .which will only be unearthed 50 years later by Illinois lawyer Abraham Lincoln. Elsewhere, Grover Cleveland pinpoints the killer of a newspaper reporter while he’s on his honeymoon; Calvin Coolidge sniffs out the truth behind the demise of his disgraced predecessor, Warren G. Harding; and a train stopover in Nevada allows Herbert Hoover and his wife, Lou, time enough to figure out who offed the manager of a silver mine. Meanwhile, The First Lady Murders boasts 20 stories of presidents’ spouses (or their stand-ins) showing an aptitude for detection. In one, we see James Madison’s wife, the indomitable Dolley, using her baking knowledge to puzzle out the circumstances of a crime among White House staff; in another, Bess Truman recalls a grim secret of the White House’s construction; and in Anne Perry’s “Madam President,” Edith Wilson must ascertain who ended the life of a blackmailer bent on revealing that the president, Woodrow Wilson, may no longer be fit to fulfill his responsibilities.

***

Also worth mentioning: Night of Camp David by Fletcher Knebel (1965); Ask Not by Max Allan Collins (2013); Mrs. Roosevelt’s Confidante by Susan Elia MacNeal (2015); Executive Privilege by Philip Margolin (2008); The Better Angels by Charles McCarry (1979); Father’s Day by John Calvin Batchelor (1994); Die Like a Hero by Clyde Linsley (2005); The Big Stick by Lawrence Alexander (1986); Murder in the White House (1980), written by former “first daughter” Margaret Truman; and Elliott Roosevelt’s Murder and the First Lady (1984), the first of 20 historical mysteries featuring his mother, Eleanor, as a particularly sagacious snoop.