One of the most popular ghosts in Jamaican folklore is the White Witch of Rose Hall. According to the lore, Annie Palmer, the aforementioned “White Witch,” is said to have been a cruel mistress on a plantation. The stories claim that she tormented her husbands and her male slaves and practiced some form of “dark magic.” Her reign of terror allegedly ended after one of her former slaves murdered her. But soon after her death, she began to make terrible, haunting appearances to all who visited the property.

You can travel to Rose Hall in Montego Bay in hopes of running into Annie Palmer’s unsettling presence. But even if you don’t, other features of the house might still give you a fright. Some visitors report being shoved by invisible hands. Objects disappear and reappear. Footsteps echo through empty halls. Tour guides will probably tell you that these happenings are evidence of duppies—spirits. And at Rose Hall, they’re likely the ghosts of the enslaved, refusing to fade into history without their stories being told.

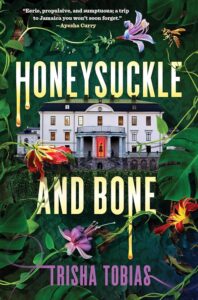

In Honeysuckle and Bone, eighteen year old Jamaican American Carina travels to Jamaica to work as an au pair for a wealthy political family. She expects some culture shock, a smidgen of homesickness, and maybe a few sleepless nights. What she doesn’t expect is to be stalked by an increasingly aggressive duppy, and for reasons she can only speculate. While Carina faces a more personal haunting in modern-day Jamaica, she discovers what locals have known for centuries: some spirits refuse to rest until justice is served.

As I wrote my debut novel Honeysuckle and Bone, I was curious about how Jamaican duppies differ from the ghosts we engage with in Western media—think the US, Canada, and Europe. Because there’s such a broad and rich folklore in Jamaica, in many cases, duppies and Western-type ghosts aren’t that different. Like more familiar-to-the-West ghosts, duppies can be helpful or threatening, or they might be completely disinterested in human affairs. But to me, the real difference comes from the way different cultures view and interact with these specters. Western media seems to walk the line of fearing ghosts while also being intrigued and even entertained by their presence. In Jamaica, the culture might lean more into respect and, at times, genuine fear.

But to understand the duppy’s position in today’s Jamaica, we have to step back to where the myth around these spirits originated: African spirituality. Note that much of what is known about the history of the duppy comes from oral tradition, creating a wide variance in what is considered “true” and how the lore behind this creature evolved. This deep-dive into the mythology, then, is a combination of well-documented history and personal speculation.

Most likely, the concept of the duppy came from African beliefs—likely Akan and/or Bantu—about humans possessing dual or multiple souls. In older Jamaican folklore, people were said to have two spirits. One was “good,” and at death, it ascended to a spiritual realm. The other was “bad,” and if proper rites were not held, that spirit could linger among the living and create chaos of all sorts.

These beliefs traveled to North America during the slave trade, becoming part of the culture for many enslaved Africans. There’s some evidence in folklore studies that storytelling was a form of psychological resistance, helping enslaved individuals cope with their oppression. So it’s possible that during this time, the enslaved people of Jamaica developed the stories around their spiritual beliefs, which might have provided some comfort. While African slaves faced unimaginable horrors, perhaps their belief in the soul’s multiplicity evolved into the idea that after death, while one soul might leave and find peace, the other could become a duppy and persist to complete unfinished business or assert itself after an unjust death.

One can then imagine that on Jamaica’s plantations, duppy stories had the potential to take on new power. Think of the popular tales that grew out of the centuries of subjugation. Instead of spirits merely taking human form, people spoke of duppies who looked like animals—like the myth of the dreaded Rollin’ (or Roaring) Calf, sporting fiery eyes and clinking metal chains. This creature offers a duppy figure who represents fear and retribution. The Calf is meant to be the twisted spirit of a person who was evil in life; in a world of daily mistreatment and abuse, then, why wouldn’t a being like this come to be?

Consider also the legend of the three-foot horse and its rider, the whooping boy. Like the Rollin’ Calf, the three-foot horse (which has three legs) might be terrifying with its flaming gaze and deadly breath. But perhaps more horrifying is the holler of the whooping boy upon its back, who is said to have been the broken spirit of a young slave. Of course someone subjected to so much pain in life would become a menace after death.

It’s plausible, then, that duppy stories developed as a way to imagine scenarios where cruel overseers and plantation owners actually had to acknowledge their crimes. Through that lens, duppy tales become more than ghost stories. They become a form of hope in a world where enslaved individuals were denied tangible justice.

But duppies were not only seen as supernatural weapons against oppressors. People needed protection from the duppies of others. Duppy catchers often used African spiritual practices to protect the living from these restless, vengeful spirits. They developed rituals to trap or banish these ghosts, and they figured out where duppies were strongest, like in cotton trees or at crossroads.

When emancipation eventually came, duppy beliefs didn’t fade. Instead, they evolved to serve new purposes.

Today’s Jamaica still bears the marks of centuries of belief in the duppy—namely, protecting oneself from them or keeping them in the realm of the dead. Lines of salt are laid to keep spirits away. Certain practices, like not announcing when you’re leaving a dead yard, or making sure your shoes face a certain way when you return home from one, are still followed by many today. In isolation, these can read as anxious superstition, funny practices persisting into a modern world. But zoomed out, these could be links to a history of resistance and survival.

The dead yard or nine-night ceremony is perhaps the most well-known and enduring practice, even if it feels somewhat removed from its multi-soul origins. Traditionally, for nine nights after a person’s death, family and friends gather to celebrate and remember the deceased in order to ensure the spirit doesn’t become a lingering duppy. Before, this practice involved more praying and singing; today, there might be more eating, drinking, and dancing. In both cases, telling stories and remembering the lost loved one is important. Even now, people try to guide souls safely to rest in their own plane.

But sometimes, even a fond remembrance and a grand party aren’t enough to soothe a slighted spirit.

Younger people today might smile at their parents and grandparents’ duppy precautions. But even for supposed non-believers, these spirits maintain a significant presence. Maybe there are more mansions than great halls now, but in Honeysuckle and Bone, Carina discovers that whether she’s on a colonial plantation or inside a gated mansion, some spirits refuse to be ignored.

Pop culture continues to pay homage to the duppy and its associated traditions. Authors weave them into their stories. Reggae and dancehall artists reference duppies in their lyrics. (Give Bob Marley’s “Duppy Conqueror” a listen.) And, of course, old traditions evolve to address modern-day fears and anxieties, the injustices of the now like police brutality or poverty. After all, the need for amends didn’t end with emancipation. The desire for hope and justice exist today. Only the means of oppression have changed face.

The power of the duppy lies in more than its ability to frighten or terrorize. Ghosts have long been used to express universal thoughts about guilt, retribution, and the heaviness of the past on the present. When truth has struggled to be heard, these vengeful duppies that were birthed from African beliefs suggest that what’s buried has a way of rising to the surface.

Jamaica’s ghosts remind us that the past and its truth can never be silenced. Not forever.

***