In 2016, journalist Amelia McDonell-Parry and I were asked to look into the death of Freddie Gray for the Undisclosed podcast, a series that focused on wrongful convictions. Gray had been killed in Baltimore police custody the year before, which led to mass protests and riots and became a national news story. State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby charged six officers on the theory that his death was caused by a “rough ride” in the van but failed to win any convictions. Gray’s death was left a mystery.

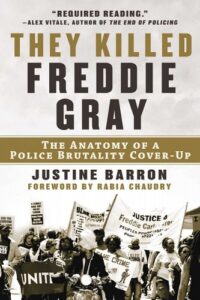

We presented our understanding of the facts in a 2017 series, challenging the rough ride narrative. After the podcast, I obtained much more evidence in the case and, this August, published a book on the subject, They Killed Freddie Gray: The Anatomy of a Police Brutality Cover-Up (Arcade). My book exposes in detail how Baltimore police and other local agencies suppressed evidence of the real cause of his death.

In many ways, my book is a classic true-crime mystery, with surprise twists, red herrings, and smoking guns. Amelia and I never considered that our investigation would be received as anything other than a typical unsolved murder podcast. Yet, I’ve learned over the last seven years that there are barriers and nuances in presenting a death-in-custody case as a true-crime story, both in the investigation and storytelling and in the marketing. I’m sharing some of these challenges with the hopes that more crime journalists and authors will seek to overcome these divides and take on these important cases.

(Note: Freddie Gray was critically injured in custody but died a week later. “Death-in-custody” is a shorthand often used within the criminal justice system to categorize cases in which a death results from a police encounter.)

Overcoming Genre Norms and Racism

True-crime books and media (podcasts, TV series, films, etc.) tend to fall into categories that don’t make obvious room for police brutality stories. Unsolved murder cases are often called “milk carton” stories, because, historically, they have tended to focus on what seem like idealized victims, young white women without criminal records or dubious histories. There are, of course, many other types of true-crime murder victims—cheating husbands, elderly parents, and so on—but usually the police in these cases have some investment in solving the crime (if not always accurately).

In the last ten years, there has also been an explosion of wrongful conviction or innocence stories. True-crime audiences have been made aware that the criminal justice system can get it wrong and that police and prosecutors are not always efficient or just in the cases they pursue.

What these two main subgenres—unsolved murders and wrongful convictions— have in common are victims who are seen to be “innocent.” In a recent event for my book, panelist Wesley Lowery (author of They Can’t Kill Us All and American Whitelash) referred to the “fetishization of innocence” among true-crime audiences, even as they have become more aware of injustices in the criminal justice system.

Many police brutality victims, too, are guilty of little to nothing when they are killed—or at most, guilty of crimes that don’t deserve extra-judicial execution. But police typically release statements emphasizing the victim’s guilt, dangerousness, and/or criminal records to limit public sympathy while at the same time framing the use of force as necessary. As in the Gray case, these media campaigns are often a strategic part of covering up what really happened. A similar smear campaigns was used by police after the 2020 killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

I have found that emphasizing Gray’s innocence on the day of his arrest, his nonviolence generally, and his known generosity and kindness within his community help rhetorically to gain sympathy for what happened to him. Otherwise, he was known to the public as a drug dealer with an arrest record.

As a result of these and other such biases, books and media on death-in-custody cases are traditionally categorized within the racial and social justice subgenre. Mainstream publishers and producers typically invest less in that category than they do in true crime, and there is more competition for the few racial justice slots. (In pitching a documentary on this case, I heard more than once that the network or producers already had in the works a story involving race or policing.)

An investigative book on a police brutality case might not end up on the shelves with the other true-crime books and might not be reviewed or featured within true-crime media, a barrier I have faced. All of this reinforces the myth that these types of cases aren’t classic murders.

Crime journalism is additionally a field still dominated by white men. A Vulture list from 2018, “52 Great True-Crime Podcasts,” included only a few podcasts about Black victims or with Black hosts.

To overcome all of these barriers, there is a need for editors, publishers, and producers to broaden their perspectives on what constitutes true crime. It already happened before, as wrongful conviction became a major subgenre. It can happen again with death-in-custody cases.

Narrating Social and Political Context

There are nuances in narrating a death-in-custody case as a true-crime mystery. Readers need far more social and political context to understand why these deaths happen and how they are covered up. Understanding motive, means, and opportunity in these cases involves recognizing how policing functions to incentivize detainments, arrests, and abuse and to protect officers. Otherwise, actions by the police in the case of Freddie Gray might seem senseless and unusual.

Granted, knowledge of social and political context is important in all murder investigations, especially wrongful convictions. But while it is widely known that, say, murdered women are most often killed by the people they know, the dynamics of policing are less widely understood outside of criminal justice circles and affected populations.

I ended up telling two stories in many of my chapters. There is a chapter on what happened when the three Black cops who were charged by Mosby interacted with Gray at the third, fourth, and fifth stops made by the transport van during his long six-stop arrest. These officers ended up unfairly saddled with the largest burden of responsibility for what happened to Gray. This chapter includes a discussion of the history of racial dynamics on the police force, because that history was very present on the streets during Gray’s arrest and during the investigation that followed.

Accessing Evidence

From an investigative standpoint, police files in death-in-custody cases are simply harder to access than in most cases. As I have learned, the minute police harm someone in custody, there is an internal effort to suppress and manipulate evidence and control the narrative. The ease and rigor with which my book shows police engaged in a cover-up, while promising the public transparency, shows how routine this type of behavior can be within departments. And in our case, the prosecutors that charged the officers were also invested in keeping some evidence from the public, as it didn’t align with the (faulty) case they presented.

To access the buried files in a death-in-custody case, it’s important to be persistent in making requests and to build relationships with sources. Amelia and I found answers in eyewitnesses who were minimized by police and prosecutors but gave similar accounts of excessive and deadly force during Gray’s arrest. We spoke to many eyewitnesses directly, and we uncovered the statements they gave to investigators in the aftermath of Gray’s arrest. Gaining access to these statements and other evidence took many Public Information Act requests over several years as well as developing relationships with anonymous sources who believed in accountability.

An Insider View

For any true-crime investigation, it is helpful to understand the inner workings of police departments and other criminal justice agencies. It is, again, essential in these cases as police will often release “evidence” that is partial or manipulated when their own officers are suspects.

In the Freddie Gray case, the police released some of the dispatch calls made among the officers. But there were also computer-aided dispatch (CAD) reports that shed light on the rest of the calls they made. We learned from sources and research how to analyze these confusing documents as well as how to figure out which CAD reports were still being suppressed. Some of these documents were major smoking guns. Police sources were also extremely helpful in interpreting whether the actions of officers that seemed suspicious were signs of a cover-up or their normal behavior.

A Call to Crime Writers

These are just some of the challenges faced in examining a police brutality case as a true-crime mystery, but they are challenges worth overcoming. The true-crime genre should represent the full range of crimes experienced by the public. It should continue its legacy of helping achieve justice where people have been wronged and the system has failed.

The Freddie Gray case is one of many death-in-custody cases in which police accounts don’t align with the known evidence or common sense. Texas police claimed that Sandra Bland, after a police stop, hung herself by a plastic bag in a police station. It was an unlikely story for so many reasons, including that she had just returned to her home state to start a new job and was excited about it. Stories like hers have all the elements that true-crime audiences look for in their narratives. She and the countless other victims of police violence, known and unknown, deserve deep investigation and compelling storytelling too.

***