When people hear that I’m a writer, there’s one question that they always ask: So, what kind of books do you write? It’s a sensible question, of course, but it’s very hard to answer. Um, I want to say, well, books about power, books about joy and betrayal and seduction, books about love…? But those answers are not the kind that most people are looking for, and so I find myself trying to describe the genre of my books. Historical magical realism, I say, or maybe historical sci-fi. Historical, anyway. At least, sort of. That is, the most recent one is set in the nineteenth century. I mean, not exactly the real nineteenth century, obviously, but… um… Yes, well, anyway, what do you do for a living?

Thankfully, I don’t really have to arrive at a good answer. It’s the publishers, not me, who have to make the final call about how to label my books and how to convince the right readers to pick them up. But those conversations make me think about genre, and how we often imagine that it’s a series of profoundly different categories, with well-defined boundaries and easily identifiable tropes; and how, most of all, we think of “genre” fiction and “realism” as being qualitatively different, as if authors took a binary decision about whether to write about the real world or an unreal one.

At first glance, that assumption makes sense; but speaking as an author, it doesn’t resonate with me. Genre, to me, isn’t a question of picking a label. It’s more as if it’s a spectrum, and the choice I make is not about accessories— Dragon? Fantasy! Spaceship? Sci-fi!—but about where I draw the line between reality and fiction, truth and invention. To start with, no novel is ever set in the real world. If it were, it wouldn’t be a novel. On the other hand, all novels are about the real world, which is why we read them—and why, I think, there are some rules which are pretty much universal and immutable, whatever the setting (the rule of causality, for example).

All fiction is speculative. It all poses the question: what if…? At one end of the spectrum you might be writing about a real person, doing the things she really did on the real dates she did them; at the other you might be writing about Middle Earth or the Discworld. But somewhere there is a line between reality and fiction, a gap filled with imagination rather than truth. The bubble of invention might be as tiny as a seed inside your character’s head, with room for nothing but her thoughts, or it might extend beyond the boundaries of the landscape, enclosing a whole universe (or, ahem, multiverse). But it’s there, and it’s the exact same thing: the place where reality and fiction brush up against each other, fizzing.

In some ways the placement of that boundary depends on predictable factors. The smaller the circumference, the less scope you have for creativity and the more accurate your research needs to be. Neither is exactly easier, though; you just have to choose between the two disciplines of accuracy and consistency. It’s easy to think that if you invent a whole world, no one can tell you you’ve got it wrong—but you can get it wrong, all the same. In the real world, you can rely on the laws of reality. The sky is blue, fire burns, electricity turns on lights. Everyone knows those things happen. You don’t have to understand or justify. But if you’re the only one who knows how the world works, you really do have to know. If you’ve got a dozen moons, what does that do to the tide? If some animals talk and others don’t, why? You don’t get carte blanche, even inside your bubble: it has to feel just as real as the room your reader is sitting in. So when you’re writing, some of that decision—let’s be honest, maybe most of it—is just about what sort of thinking you like best. Do you enjoy the mastery of learning new things? Or would you rather go through the details of your daydreams, obsessively ironing out the wrinkles?

But it isn’t only a question of the writer’s temperament or inclination. By choosing where your fictional world begins and ends, you’re choosing what your book is about. Remember I said that the boundary fizzes? That fizz is the story. It’s the friction between what we recognise and what we don’t that forces us to look, to pay attention. So if the only thing your world has in common with the real one is humanity—or intelligent life—that’s your subject. If the only thing your world does not have in common with the real one is the interior life of an otherwise real person… well, you get the idea.

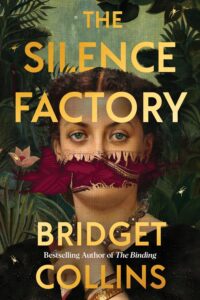

So for me, that zone—the experimental zone, really, where the effects of the what if premise can be most clearly seen —is the most interesting place in a novel. And deciding on its exact location can be unexpectedly tricky, even when you know more or less where you want it. In The Silence Factory, for example, I knew that I wanted the world to be more or less the nineteenth century, and the setting the West of England—more or less Devon; I knew, in fact, that the town was more or less the real town of Tiverton, and the house more or less the real house of Knightshayes Court. I knew too that the protagonist’s home was in London, which was more or less the real London.

But “more or less” is not good enough; the setting had to be exact and immersive, full of names and details. What I wanted was as real a world as I could get away with, given my speculative not-quite-supernatural premise: a world that would be a perfect petri dish for a “what if” about industry and patriarchy, privilege and sexuality and British colonialism. I wanted the story to have roots that went right down into real places and times – but at the same time I knew that reality had to budge up to make room. Too specific a setting would be distracting and rigid. It is a fact that Tiverton never had a factory that spun spider silk; but if I drew my fictional bubble a little wider than the factory itself, Tiverton could become Telverton, just as Knightshayes Court could become Cathermute House, leaving new space for possibility. Where the focus was not as sharp, there was less need to sidestep the reader’s disbelief: further out, in the blurred background, Exeter remained Exeter, and Devon remained Devon—and, of course, London was London (although that is partly because nineteenth-century London is a special case, almost a fictional place in its own right, like fourteenth-century Verona or the Forest of Arden).

I realise I am making it sound as if the process of choosing a setting was very considered – as if I did this and this, because of this and this – and, of course, writing is not like that at all. Most of the time you are working by instinct, taking the path that you hope will lead you where you want to go. The only thing that you can rely on is the voice in your head, the one that is always asking, yes, but what would it be like, really, if…? So I renamed Tiverton Telverton, but I kept the street names, hoping some of the reality would cling to them; I did not specify a year, but I researched the exact dates of Punch cartoons, to check that my hero could have seen them; no one real actually appears in the book, but my characters namecheck Florence Nightingale and Thomas Braidwood and Christina Rossetti. My Greek island is entirely fictional, but I knew when the forest fires had decimated the oak forests, years after my heroine had left it behind for good—and so on, and so on. It was superstition, in a way, but also a kind of conscientiousness, a reminder that having sacrificed literal reality hadn’t absolved me of making the fictional world as real as I could.

One of my favourite books (I was going to write, “as a child”, but hey, it’s still one of them) is Fire and Hemlock, by the masterful and brilliant Diana Wynne Jones. It’s a wonderful, complex, funny book, where the boundaries of real and not-real waver and dissolve and reform, and at the centre of the story is the image of two spinning vases, both with NOWHERE carved on them. Sometimes after they’ve been spun they spell NOWHERE; sometimes, HERE NOW; sometimes, WHERE NOW? For me, that metaphor is a perfect one for fantasy, and for fiction. It’s my job, when I’m writing, to make NOWHERE feel as close to NOW HERE as it can be: and it’s in the space between, with one hand on each, that you find yourself in exactly the right place, asking the right question.

***