My debut novel is a tribute to my hero, Jane Austen, in the format of a murder mystery. It is fitting because Austen’s classic works are essentially mysteries where the heroine must uncover the true characters of those around her, especially the hero. In a world where a women’s entire future depends upon who she marries, it pays to investigates one’s love interest thoroughly. With that in mind, here are all six of Jane Austen’s heroines, ranked from worst to best for their detection skills.

There is one young woman who combines all these qualities in abundance and whose prowess at sleuthing outshines even her greatest protagonist, and that’s Austen herself. Throughout her works and letters, she displays an innate understanding of human nature, a passion for justice, and an unflinching gaze at the mercenary society which she inhabits. That’s why, when I was looking for a way to tell Austen’s life story, I couldn’t resist making her the star of her very own murder mystery. In this first installment, Miss Austen Investigates, The Hapless Milliner, my Jane is very young and most definitely in her Catherine Morland era. However, when the body of a milliner is found bludgeoned to death at a ball, and Jane’s gentle brother Georgy is thrown into gaol, nothing will prevent her from using her sharp wit and fierce determination to uncover the true culprit and save Georgy from the gallows.

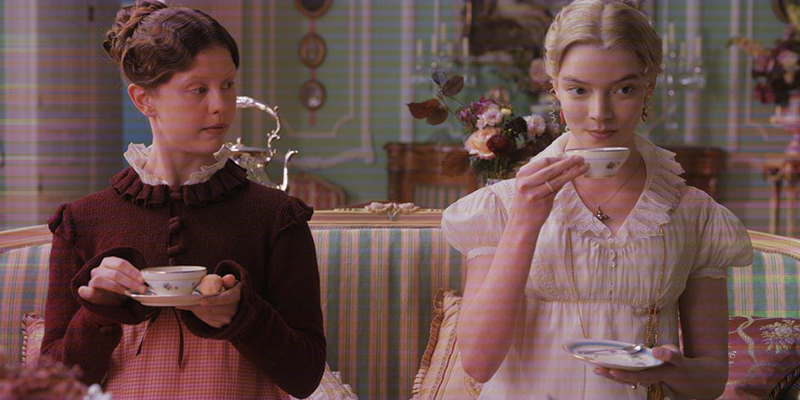

Emma Woodhouse

It’s ironic that Austen’s most lacklustre sleuth is the protagonist of her most perfect mystery, for Emma follows the conventions of a contemporary whodunnit. There’s no dead body, but Austen cleverly sprinkles the clues as to the real story, the secret engagement between Jane Fairfax and Frank Churchill, throughout the narrative. Unfortunately, Emma is too self-absorbed to spot them. The sheltered life she’s endured trapped at Hartfield with her controlling father, combined with her extreme privilege, have left her bereft of insight. She really is clueless. Although Emma develops enough self-awareness to regret her terrible behavior and understand her romantic feelings for Mr Knightley by the end of the novel, in terms of sleuthing skills, I’m afraid it’s ‘badly done, indeed!’

Catherine Morland

Catherine should be most suited to a life of solving cozy crime. The ‘horrid’ Gothic novels she’s read (the Regency equivalent of our true crime obsession?) make her an expert on dastardly deeds and she’s on the hunt for the truth about what happened to the former mistress of Northanger Abbey as soon as she arrives. At first, it might seem as if Austen is encouraging us to laugh at Catherine’s wild imagination when she accuses General Tilney of murdering his wife. Catherine is certainly mortified and allows herself to be persuaded out of her convictions by Henry Tilney’s pompous sermon. But it’s hard to ignore the fact that Catherine turns out to be right – there is something monstrously callous about General Tilney, who throws teenage Catherine out of his house, at a moment’s notice and with no protection, for not being as rich as he thought she was. Excellent instincts Catherine.

Fanny Price

Unlike Emma and Catherine, poor Fanny doesn’t have the luxury of complacency. Having been ripped away from her family and emotionally abused by her wealthy relations, Fanny is constantly on her guard. Rightfully so, as one wrong move and she’s sent back to her negligent parents as punishment for refusing a socially and financially advantageous match in Henry Crawford. But Fanny won’t bend. She saw through Henry’s roguish charms the moment he arrived on the scene. Her lowly status and her own timidity leave her powerless to prevent the corruption wreaking havoc at Mansfield Park—from the inappropriate choice of amateur dramatics to the slavery it’s built on—but she sees everything, and, through her, we see it too. In Fanny’s own words: ‘I was quiet, but I was not blind.’

Elinor Dashwood and Anne Elliot

Joint runners up are ‘sensible’ Elinor and ‘capable’ Anne. Their steady temperaments mean others are constantly confiding in them, even when Elinor and Anne would rather they did not. Colonel Brandon trusts Elinor with the tragic tale of Eliza Williams because, unlike the emotionally incontinent Marianne, he knows she can govern her response to it. Lucy Steele forces Elinor into her confidence to warn her off her fiancé, and even Willoughby has the gall to make Elinor his confessor. Rather than collapsing under the burden of everyone else’s admissions, Elinor discretely uses this knowledge to navigate towards a satisfactory conclusion. Similarly, Anne’s legendary tact means she’s forced to listen to the complaints of her various acquaintances and given the task of babysitting the insufferable. While Anne may not relish an evening of Benwick’s mournful poetry, it is her gentle probing of the melancholy captain which causes Wentworth to realise he’s still in with a chance. Nice work ladies.

Elizabeth Bennet

Mr Darcy accuses Lizzy of setting out ‘wilfully to misunderstand’ everyone she meets, but he’s as wrong about her as she was about him. When Lizzy realises the discrepancy between Wickham and Darcy’s accounts of their prior relationship, she proactively sets out to investigate by questioning the witnesses (including Aunt Gardiner and Pemberley’s housekeeper) and weighing up the probability of one man’s version of events against the other’s. It is to Lizzy’s credit that she’s ever willing to be proved wrong and, even better, to examine why she might have let herself be deceived. She can even laugh at her foibles. This delightful humility throughout her epic journey of self-discovery is what makes Lizzy not only Austen’s best detective, but also her most beloved heroine of all.

***