The frontier station of Dauria, in the Trans-Baikal region of Russia, was a garden of bones.

They littered the land for miles around. The dirt floors of the stables of the headquarters of the Tsarist commander were stained with blood, and chunks of flesh and hair hung from metal rings, where tortured prisoners suspected of Communism or Judaism had met their ends in unspeakable pain and brutality. It was the Russian Civil War; one of the most savage and fratricidal conflicts of the twentieth century. The Whites controlled the rail line through Siberia, and the Bolsheviks were far away to the west. Here, the commander of the Czarist forces, ruling the surrounding area with a brutal, iron fist, like the medieval baron he effectively was, was Nikolai Robert Maximillian Freiherr von Ungern-Sternberg. He was among the most brutal, dangerous, and deranged generals in an army that had a well-earned reputation for being brutal, dangerous, and deranged.

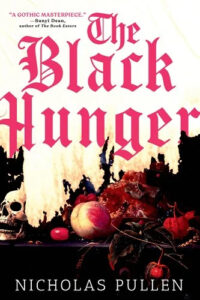

He is also debatably the main antagonist in my horror novel, The Black Hunger, which was published this week by Orbit Books. Ungern, as he is known in the dark, terrifying corners of the alt-right internet where he is worshipped as a hero, is the ultimate proto-fascist; a symbol of the seductive, siren lure of fascism; one of the modern era’s most durable and reliable sources of horror, terror, and death.

I met the baron in my early twenties, at a time in my life when I was myself a little unstable, struggling to comply with my treatment for Bipolar I. I was aimlessly browsing an Indigo in Toronto, my hometown, and he locked eyes with me from across a crowded room, commanding me to come to him.

He was on the cover of a book called The Bloody White Baron, by James Palmer. It was a photo of him taken not long before his execution by the Bolsheviks, and he does not look at all well, if he ever did. His eyes are cold, cruel, and dead, without a spark of humanity, joy, or humour. I would say this was to do with the circumstances of the photograph, but as I discovered more about him, it became increasingly clear that this was a man who did not laugh, unless in cruelty.

He was a Baltic German aristocrat, with family roots in what is now Estonia that went back to the days of the unfathomably brutal crusading order of the Teutonic Knights. The Baltic Germans were among the Tsar’s most fanatically loyal subjects, and had a long tradition of military service to the Tsar and his regime. Ungern was the sort of child who tortured animals and his peers, physically and psychologically. He was not a bully. Even the bullies were terrified of him. He was quickly banished to military school, and entered the service of the Tsar as a young man. He was quickly broken to the ranks for his astonishing, unpredictable, and random cruelty to his fellow officers, his soldiers, and civilians. You really had to stand out to achieve such a feat in the Tsar’s army.

Fascism was yet on the horizon, but all of its primordial elements were already present in the mind of young Ungern. Fascism explicitly rejects Christianity as weak, effete, a slave religion, a Jewish poison corrupting the spirit of the Aryan race. Hitler and his acolytes openly intended to replace the Christian Church with a ‘National Church,’ with Mein Kampf on its altars. The Nazi Party’s earliest origins are in the Thule Society, an occult organization that made its members sign a pledge that they had no Jewish ancestry whatsoever.

Ungern, of course, despised Jews as alien, sinister, and dangerous, and despised Communism, then on the rise in Russia, just as much. Ungern failed at all of his formal education, but acquired an enormous, autodidactic, and eccentric education in Theosophy, one of many occultist movements active in Europe in the early twentieth century, and became increasingly obsessed with Vajrayana Buddhism, seeing in it a purer, manlier, more honest faith than what he saw as the debased Jewish poison of Christianity. He was fanatically loyal to the Tsar, who he saw as chosen by God, though how he reconciled that with his occult beliefs is a matter of mystery to anyone other than him.

Like so many men like him, he was saved by the outbreak of the First World War. War was what he was born for. He existed to kill. By the time the February revolution broke out, toppling Tsar Nicholas II, he had made colonel. As Kerensky’s provisional government was destroyed by the Bolsheviks, he quickly became a leader in the diverse ‘White’ Russian forces opposed to the ‘Red’ Bolsheviks, and as the war progressed, he found himself in Siberia, helping to control the Trans-Siberian Railroad and earning a legendary reputation for cruelty and barbarity.

As the war began to turn against the Whites, he conceived a scheme to conquer and rule Mongolia, ostensibly to support the Bogd Khan, Mongolia’s Buddhist spiritual and temporal leader, who had recently declared Mongolia’s independence from a collapsing China. Ungern led his army into Urga, or Ikh Khuree, now known as Ulaanbataar, in 1921, where he was declared the Tsakhan Burkhan, god of war. His reputation for cruelty and brutality there endures to this day.

Ungern was attributed supernatural powers by his enemies. He seemed impervious to bullets. He skipped and danced in the heat of battle like a little girl. Bullets seemed to bounce off him. He claimed to be able to read minds, and would execute people whose thoughts he could see were disloyal. He knew the White cause was finished. As a last ditch attempt to stop the Jews and Communists, he believed he could muster an army of horse lords, as a reincarnated Genghis Khan, to conquer the world, and wipe out the Jews and Communists to the last man, woman, and child, thus restoring the natural order of things: the dominance of the Aryan race. The enterprise was quixotic, to say nothing of stupid, in the age of the machine gun, and when he failed, he was executed by the Bolsheviks after a well-deserved show trial.

One of the germs from which my own book grew was the simple thought: what would it have taken for his evil, terrifying, apocalyptic scheme to have succeeded?

I have a rather broad, holistic interpretation of horror, and what it constitutes. One of horror’s most enduring and powerful uses as a genre is to reflect our own fears and anxieties back to us. Though we may think these fears are personal to us, unique, they are often in fact manifestations of the fears that grip the zeitgeist of our wider society. Thus, the vampire’s roots in the Victorian era reflect that generation’s fears and loathing of sexuality. The zombie, with its roots in a misunderstanding of Haitian religion, reflects both American racism and fear of a black other, and in more recent decades, our dread of the apocalypse we are manufacturing for ourselves.

The Black Hunger was semi-consciously written under the influence of my own terror, as a gay man, certainly, but also as a human being, at the rise of the euphemistically termed ‘alt right,’ which is internet marketing speak for fascism.The Black Hunger was semi-consciously written under the influence of my own terror, as a gay man, certainly, but also as a human being, at the rise of the euphemistically termed ‘alt right,’ which is internet marketing speak for fascism. Obviously I’m not speaking of any particular Italian political party from the 1920s. I’m speaking of it in the sense Umberto Eco did: as ur-fascism, eternal fascism, an easily recognizable and definable tendency towards nationalism, contempt for law and institutions, and hatred. Our contemporary fascists may have (largely) abandoned their obsession with Jews, and prefer instead to focus on migrants and on proponents of ‘gender ideology,’ but if they do succeed (as they are beginning to in Italy, Hungary, and perhaps the United States) the death camps they establish will be populated by much the same group of ‘undesirables’ they were in the 1940s.

Like the vampire, part of the terror of fascism lies in its power of seduction. It is not always ugly. If evil things were always ugly, the world would be a much simpler place. It is easy, if one is not on guard, to be seduced by the power, the elegance, the thrill of seemingly simple solutions to complex problems. It’s the fault of the Jews, for example. Or the immigrants. Or the queers. The bogeymen change, but the lure of the easy enemy, the simple solution, never does. Fascism revolts against a messy, nuanced, complicated world, where there are no easy answers and no obvious order. Fascism craves order, simplicity, purity. And it is always prepared to kill to acquire it. To punish. To destroy.

The Black Hunger centres around a cult of reactionary occult fanatics, led by a fictionalized Ungern, and by the Count Evgeni Vorontzoff, determined to wipe out all life on earth in accordance with their perversion of Buddhist theology. They are as nihilistic and deranged as Hungary’s Jobbik Party, or France’s National Rally, or the dominant strains of America’s Republican Party. But there is an allure to their evil; to their desire to destroy. Evgeni is by design a seductive character. In the case of the Dhaumri Karoti, my cult, it is not just Jews, or Marxists, or Queers, or Muslims, or Migrants, but life itself that is to blame. This, in the end, is what fascists oppose: life, in all its variability, nuance, and complexity. They want to burn and destroy, not build and redeem. As far as they are concerned, death and terror are ends in themselves, not means.

The Dhaumri Karoti are fictional, and it is nowhere yet a matter of public record that our twenty-first century fascists are members of a cannibal cult (though nothing would surprise me at this point), but it doesn’t take long delving into the darkest corners of the fascist internet, whether in the netherworld of alt-right Twitter, or in the writings of Bronze Age Pervert or Mencius Moldbug, to find Ungern spoken of reverentially, almost religiously, enshrined in memes and fan art, and in text, as the harbinger, the man who saw what was coming and tried to stop it. They adore him. Indeed, to be aware of him at all, is usually a terrible sign. If someone you know has heard of him, you should regard them with at the very least wary suspicion, until they’ve shown you how and why they know who he is.

I like horror that plays for high stakes. The slasher and the serial killer and even the vampire are not for me, much as I love and respect them. I’m drawn to the apocalyptic, the earth-shattering, the epochal. I want the fate of our civilization to be the stakes of our game. This is why I love the occult, tampering with demonic, unstoppable forces. This is why I love the Lovecraftian cultist and the Great Old Ones, with their resonance of unfathomable purposes and apocalypse. This is why I love the zombie. It represents death; uncaring, unreasoning, unstoppable death. And not just my death. Yours, and everybody else’s as well. The Dhaumri Karoti, Count Vorontzoff, and Baron Ungern are playing for high stakes in my novel. So are my protagonists.

And in the global fight against fascism, so are we all…

***