The notion of “Identity” can be regarded in multiple ways:

Identity (noun):

- the condition or fact of being a specific person or thing;

- the ways that people’s self-concepts are based on their membership in social groups;

- the characteristics and qualities of a person, considered collectively and regarded as essential to that person’s self-awareness.

This discussion explores ways in which each of these concepts can be central to crime fiction and how, as an author, I have explored each of them.

*

In mysteries and thrillers, it’s often customary to follow a plot to find out “Whodunnit?”, that is to uncover the identity of the perpetrator of an illegal act. Some crimes suggest the offender knew the victim. In this case, friends, lovers, exes, co-workers, and acquaintances may be scrutinized to determine motive and opportunity: Had they recently broken up? Were they arguing? Did someone harbor a long-held grudge against the victim? Were they spotted together just before the crime?

Other offenses may appear to have occurred at random, and the breadth of possible suspects is wider. Did anyone near the incident see anything unusual? Hear something? Was anything left at the crime scene to provide a lead?

In either case, the detective or protagonist looks for clues—often left unintentionally, sometimes deliberately—and uses these scraps of information to lead them to the culprit. The perpetrator dropped cigarette butts, left heel prints from size 10 boots in the dirt outside the crime scene. Witnesses saw a Chevy van with New Jersey plates careening away at the time of the incident. It’s the detective’s skill in recognizing, pinpointing, and determining the significance of such clues that brings the quest to a successful resolution, and the identity of the perpetrator is revealed.

But often the pieces don’t come together smoothly, and the investigation involves misidentification of suspects. In my 2009 novel, The Labrys Reunion, a group of women gather to mourn the murder of one of their daughters. Frustrated by the perceived indifference of the police, they follow clues that seem to suggest a suspect. With no training, only a fervent thirst for justice, they take it upon themselves to detain this potential perpetrator and, overcome with a lust for vengeance, almost become executioners of what turns out to be an innocent man.

“Whodunnits” primarily concentrate on the first definition of identity provided above, to name and apprehend the guilty party. It’s somewhat rarer to concentrate on the psychological profile of the perpetrator, although in some novels, readers may learn a lot about this in the search for clues.

The reader is also sifting for for evidence right alongside the investigator, and making determinations about whether we draw the same conclusions or have our own ideas about who the offender might be. This engagement of the reader, drawing on our own skills of assessment and discernment to weigh and discard possible scenarios, makes crime novels such an exciting read.

*

Beginning in the late 19th century, mysteries began to introduce detectives of diverse identities—female, Asian American, Native American. Often, these characters were drawn from the imaginations of writers who were white and male and could therefore present inauthentic or stereotypical representations, such as in Earl Derr Biggers’ characterization of the detective, Charlie Chan.

While women writers and writers of color were publishing detective fiction during this period, they often chosen protagonists who were white and male, perhaps due to commercial considerations. Although José F. Godoy is considered the first Latin American writer to write a mystery novel (Who Did It? The Last New York Mystery,1883), and Todd Downing of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma was one of the first commercially published mystery writers of Native American descent, both Godoy and Downing chose to feature white protagonists.

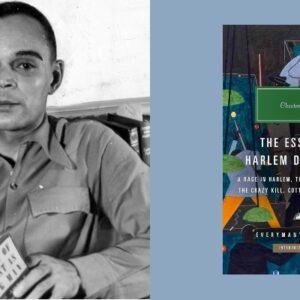

The exception seems to be African American writers who, as early as 1901, featured Black detectives in their work. Perhaps due to the dearth of opportunities to publish in white publications, they understood their audience to be Black readers. In both Pauline Hopkins’s Hagar’s Daughter (1901-02) and John Bruce’s The Black Sleuth (1908-09), the authors incorporate black vernacular, the music of black speech, as well as detectives whose black identity is essential to the solving of the murders. These novels also function as social critiques of pre-and post-Civil War racism, and pave the way for writers of diverse backgrounds to use the mystery genre as a vehicle for heightening awareness of the issues confronting their communities.

From the mid-20th century to the present, female, Latino, Native American, Asian-American, and LGBTQ as well as African American writers explore their identities and communities through crime fiction. Leading with protagonists who represent those communities, stories reveal the social identities of and demonstrate how the protagonists are up against straight, white, male-dominated structures. Often these protagonists are called upon to prove themselves to a mainstream culture that questions their abilities.

The protagonists in my novels are always lesbian and the stories illuminate aspects of that community. In my 2011 novel, Stealing Angel, the protagonist kidnaps the daughter she has co-parented when she learns that someone close to her ex has been physically abusing the seven-year-old child. She leaves the familiarity of her community and heads for a spiritual commune in the southern Baja. There she is an outsider, because she’s a lesbian, is not a member of that insular community, and its members disapprove of her choice to abscond with the child. She must win the trust of the community to gain their help.

*

In the psychological thriller, we may find more emphasis on the identity of the protagonist, who must resolve internal issues in order to survive the threat to them.

In my most recent novel, Season of Eclipse, the protagonist loses her sense of self when she is forced to relinquish her identity and construct another. Marielle Wing is a successful author who unexpectedly witnesses a large-scale, public crime. As someone who may have seen the perpetrators, she is forced to enter the Witness Security Program and thus, give up her identity. Relocated to a new part of the country and assigned a new name and birthdate, she must then construct a new self-concept and story. This won’t be the first time she undergoes a change of name and visual appearance as she struggles to stay out of the clutches of those who are looking for her.

This brings to the forefront the question of Who am I? once the trappings of our lives are stripped away. While not all of us solve crimes or go undercover, nearly everyone at one time or another must revise our self-image—whether as a result of marriage or divorce, parenthood, job change or job loss, or coming out. This aspect of identity turns out to be one with which most readers can readily identify.

***