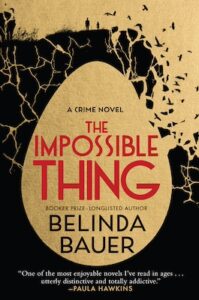

When I pitched The Impossible Thing to my publisher, his eyes glazed over.

Embarrassed, I changed the subject. I already knew it was a weird one: The true story of thirty miraculous red eggs that were all taken from the same guillemot, sold to the highest bidder for a small fortune, and then somehow disappeared, never to be seen again.

I thought it was a crime novel where the victim was a bird, and a wonderful mystery.

Apparently I was wrong.

I tried to forget about it, but that sad little seabird that never raised a chick haunted me. Over the next few years I’d try to explain the story to people, but it was never received with enthusiasm.

Finally my brave publicist asked one critical question:

‘B,’ she said hesitantly, ‘Does the bird talk?’

‘What?!’ I said, aghast. ‘NO!’

‘In that case,’ she said. ‘I LOVE it!’

And I realised where I’d been going wrong.

Anthropomorphism.

When it comes to fear of ridicule, it’s right up there with Bigfoot.

Enlightened and relieved, I wrote the book.

But I still think about that question all the time…

No, my bird doesn’t talk, but if I’d felt it would serve the book, I would not have demurred. And I do give her emotions. Limited bird-emotions, admittedly, but I believe animals have feelings, that they communicate more efficiently than we do, and that we do them a disservice when these things are discounted.

I have given animals bit-parts in most of my novels, and it confuses me that more people don’t. We live alongside animals, spend billions on their care, talk to them, enact laws to protect them, worship them as gods, dress them like babies.

Adult fiction has occasionally veered towards rocky anthropomorphic shores, but it’s only when the motives attributed to the animal are antagonistic or satirical that such fiction becomes ‘respectable’. Moby Dick must be allowed his vengeance, and Napoleon his revolution. Other mainstream books, such as Watership Down, that dare to imagine animals talking to each other, are regarded as mere fantasies.

Conversely, children’s stories are crammed with animals displaying every possible emotion, and our own lives are shaped by these formative tales. We all cried when Bambi’s mother was killed, we rooted for Babe the sheep-pig, and we cheered when Dumbo spread his ears and flew.

But we are conditioned to mock the very idea that a cow might cry for her stolen calf.

When does it change? And why? When does treating animals as thinking, emotional beings suddenly become a wholly crazy notion, like Santa Claus or the tooth fairy? And how does it serve us to shed our belief in the connectedness of all living things and to regard animals as unfeeling and mute? Is it a convenience that shields us from how badly we misuse them? If we didn’t mock anthropomorphism so ruthlessly, could we really eat Bambi? Hook Dory? Murder Eeyore for his skin?

So childlike compassion is derided and we fold under peer pressure.

Ironically our language – bacon, steak, hamburger – distances us from the animals that are the source of these meals. Our denial runs deep. Who knows, if only we called it ‘long pig’, could we more easily overcome our aversion to cannibalism? Why not? We already pick and choose those marked for exploitation and consumption because we have been convinced they are ‘less than’…

Is the power of speech the only thing that stops us?

The saddest thing about this ridicule is that the very thing we’re being made to feel embarrassed by – and the only thing we lose by it – is the one thing that anthropomorphism teaches every child.

Empathy.

And where is the benefit to society in reducing our collective empathy?

I am grateful to report that, overwhelmingly, the readers of The Impossible Thing have been moved by the book – instinctively grasping the sorrow of the bird, the horror of the sport of egg collecting, and the shame of man.

Maybe it’s only our lingering memories of talking bees and bears and butterflies that keeps us from treating animals – and each other – even more badly than we already do.

Anthropomorphism?

I’m all for it.

***