I am obsessed. I can’t escape it. My thoughts are dominated by the evil, the mystery, the cruelty of one eccentric episode in modern history: The Cold War.

It’s what I read. It’s what I write. It’s my lens for the world.

And, even though the Cold War was pronounced dead with the fall of the Berlin Wall at the end of 1989, I see evidence of the Cold War around me daily, lurking like some half-seen figure in the shadows.

The war in Ukraine? The daily propaganda messages from the Kremlin, amplified by China’s supportive posturing against the West, is the mirror image of events from the Korean War of the 1950s, when China was the combatant and the Soviet Union was the supporter.

Strange theories about Covid or Monkeypox hatched in secret labs? Reminds me of the fears of bioterrorism immediately following WWII that led to the creation, for military purposes, of what today is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Fear, mystery, hidden forces, alien powers, random chaos pushing people towards nihilism, those are the key issues of the Cold War. And they remain alive and well-fed in 2022, fueling a renewed interest in the Cold War in literature, film and television. To be clear, I take a broader view of the Cold War than simply defining it as the era of Soviet-American tensions between 1945-1989. That is the true Cold War. But to me, the broader, literary idea of the Cold War extends to any era in which enemies unknown threaten the stability, the livelihood and existence of regular people in a period where, officially, no war exists. George Orwell’s 1984, published in England in 1948? Absolutely Cold War. Amazon Prime’s 2015-2019 series The Man in the High Castle, based on Phillip K. Dick’s 1962 alternate history in which America loses WWII and is subjugated by the victors, Japan and Germany? Totally Cold War.

There was a time in the late 1970s through the 1980s, when Cold War spy stories dominated the book trade like massive nuclear-armed missiles on the horizon. John le Carré’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, Len Deighton’s Game, Set, Match series, and others were the epic novels of the era, lovingly and painstakingly turned into television miniseries with big budgets and headline actors. But all that faded away for a few decades when the Cold War was said to have ended. Cold War, dead. Spy stories, out. But, like radioactive dust, the winds have blown life back into the Cold War.

One of the best detective thrillers of 2021, according to Stephen King: Five Decembers, a brilliant saga by James Kestrel, set in Hawaii and Hong Kong spanning pre-Pearl Harbor to the end of WWII. The book is crammed with mysterious espionage forces and clandestine military preparations when neither America nor Hong Kong were officially involved in war. New Cold War thrillers out this year include Joseph Kanon’s The Berlin Exchange, the story of a spy swap, and Anika Scott’s The Soviet Sisters, also set in Berlin, but from a distinctively Eastern perspective.

Here’s my bet: We are going to see a continued rise of new Cold War books, especially Noir tales, in the next two years. Just as the Kennedy assassinations in the 1960s, the Watergate break-in and coverup in 1972, and the CIA-backed coup and assassination of Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973 led to a slew of government conspiracy-laced thrillers, like James Grady’s Six Days of the Condor and Frederick Forsyth’s The Odessa File, I think we are ripe for an exploration of unsettling forces loose in the world today.

Why? Because literature becomes a go-to, partly for solace to heal and explain modern tensions through the lens of history, and partly to echo and reinforce themes of alienation, anxiety and social distress, much like a tongue probing a chipped tooth. After all, when Mickey Spillane’s private eye antihero Mike Hammer decried his essence as a government-trained, war-inured, legalized killer in One Lonely Night, published in 1951, he was reflecting back more than a decade of turmoil, doubt and repercussions from World War II. And readers loved it.

From my scan of the horizon, there are a handful of wild forces at play that are unlikely to be tamed any time soon: mistrust for government, fear of war, whether conventional war or cyber-war, and fear of increasingly powerful and seemingly malevolent technology. After all, who isn’t, deep down, afraid of what Google or the NSA knows about them? Throw in a few conspiracy theories smoldering on the internet and you’ve got the seeds for a new crop of Cold War novels.

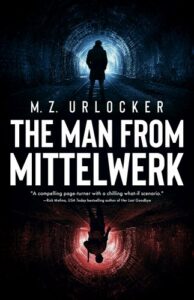

My own novel, The Man from Mittelwerk, is set in California in 1950, with a traumatized World War II vet facing his worst nightmare, the appearance of Nazi scientists in America. (This really happened: The U.S. imported 1,600 top German Scientists under a secret program called Operation Paperclip.) I don’t want to spoil the story here, but I will say, even though it’s a Cold War thriller with spies and codes and a few murders, it’s actually a critique of our modern obsession with technology.

As a writer, the Cold War is an extra character that serves as the best sort of Noir villain, hidden, cruel, unpredictable, like a poison gas in the air. I was inspired by Philip Kerr’s brilliant Berlin Noir trilogy, a Chandler-style detective story transplanted from the mean streets of Los Angeles to the madness of Nazi Berlin. Nobody beats Kerr in describing the daily life for Germans under Hitler. Kerr painted a picture of the attempt to normalize the oppression of the Nazi regime across all aspects of daily life, from the “volunteer” donation drives to the suddenly booming business for his lead character, ex-cop Bernie Gunther, in searching for missing persons, usually Jews, usually dead in the river.

On the surface, Kerr wrote detective stories in homage to Chandler, but in reality, he portrayed an epic battle of good versus pervasive evil. Whether that evil represented war or a political force or technology gone wild doesn’t really matter. It’s the struggle that keeps the reader’s interest.

In the tumultuous time we’re in, the winds of cold war continue to chill us. There are battles being fought in undeclared wars, some we know about, some we may never know. It’s in these times that people turn to Cold War noir to help them understand the world we’re in. Decades after it was pronounced dead, the Cold War lives on for readers, for writers, for all of us.

***