I think about murder a lot.

No big surprise, since I write murder mysteries for a living.

But I’ve been thinking about murder for a lot longer than I’ve been writing it. Since I was old enough to pull a well-thumbed paperback off my grandmother’s bookshelf.

Detective fiction has been my comfort food since I was a child. And my preoccupation with murder hasn’t stopped at fictional ones. If my audiobook library can be believed, I spent a large chunk of the 2010s consuming true crime podcasts and documentaries about long-caught serial killers.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about the why of it all. Why the preoccupation with murder? Why was I reading Sherlock Holmes at eight years old and Agatha Christie at ten and Stephen King (fantastical murder but still murder) at twelve? Then why the jump to Ann Rule and My Favorite Murder and other staples of true crime?

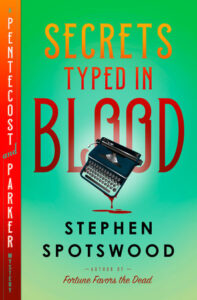

In SECRETS TYPED IN BLOOD, the third installment in the Pentecost & Parker series, my detectives’ client is Holly Quick, a pulp crime writer who discovers that someone is recreating her fictional murders in real life. The suspects include members of a private club of well-heeled men obsessed with killers. Consequently, there’s some discussion in the book about why so many people are drawn to fictional mysteries and real life murder.

Naturally, I wanted to answer that about myself.

As to the first question––why did I fall so easily into mysteries as a child–that’s relatively easy. Or at least I’ve had longer to think about it.

Yes, there’s the puzzle-solving aspect of it. I still remember the joy when I figured out who committed the murder on the Orient Express before Hercule Poirot. But if that were the only draw, mysteries wouldn’t hold up to rereads.

I think the real reason I was drawn to mysteries is very similar to the one Holly gives for writing them. Mysteries–especially of the whodunit variety–show us a world where a terrible thing has happened but we know that by the last page everything will be put right. Or as right as it can be when death is involved.

It says: Here, look, if you’re smart enough and work hard enough and get a little lucky, even the thorniest problems can be solved. For children living certain kinds of childhoods, that is extraordinarily comforting. Alternate those mysteries with some fantasy and sci-fi and you’ve got a pretty good self-care regimen to get you through to adulthood.

My later-in-life binge of true crime is a little more difficult to parse. These aren’t puzzles, after all, they’re tragedies.

In 1947, when SECRETS TYPED IN BLOOD is set, the medium for true crime stories were the pulps: Crime Detective, True Detective, Confidential Detective, Front Page Detective, Uncensored Detective. They contained articles like “I Was a Lonely Hearts Racketeer,” “I Was a Shill for a Blackmail Bandit,” “Crime Wave of the Gentlemen Crook and the Blonde Bait,” and “Nobody Else Can Have My Lady Love.”

Women weren’t always featured in the stories, but when they were, they were usually femme fatales, good girls who’ve fallen into vice, or corpses.

It wasn’t a secret who the magazines were geared towards. The women on the covers were sometimes elaborately bound and almost always in various states of undress, shrinking back from some seen or unseen assailant. The ads leaned heavily into hernia aids and hair growth potions; mail-order courses on how to be a radio operator; or “marital aid” books, which was a flimsy code for porn.

True crime in the 1930s/40s was very much about the male gaze. Men read it to be titillated, to be voyeurs to the so-called dark, underbelly of society. They also read it to have their ideas of the world and of women’s roles in it reinforced: there are virgins and whores, and it’s fun to hear how the former can turn into the latter, but don’t forget that either can end up dead if they put a foot wrong.

This is a generalization of the true crime pulps, sure. There were exceptions in the stories, and people other than balding, hernia-bedeviled men found joy in reading them. I made Will Parker, my protagonist, a fan of the pulps. Though she’d say her reasons are at least partly professional.

Her boss, Lillian Pentecost, doesn’t share that affection. At one point in SECRETS TYPED IN BLOOD, Ms. Pentecost declares that those obsessed with murder and murderers rarely afford the victims that same attention.

Which is the biggest argument around true crime today. Is it exploitative of those victims? Does it mine grief for entertainment? Is there an ethical way to consume true crime?

Most of the solutions involve centering the victims, which true crime is finally making the effort to do.

Sometimes.

Sort of.

More so when the victims are white and able-bodied and might look good in a tattered negligee.

But at least the questions are being asked.

Probably because the readers/listeners/viewers these days look more like the victims than the killer. Today, the most passionate consumers of true crime, especially stories about violent crime, are women.

The most common reason given, by both women and researchers on the subject, is that by consuming descriptions of awful things that happened to other people they can learn how to avoid dangerous situations and people in real life.

Women and gender-nonconforming individuals are more likely to be victims of intimate partner violence. They’re more likely to know their killer and have a chance of seeing the danger signs.

True crime, they say, is a master’s course in identifying red flags.

But that still doesn’t answer my own question: Why was I personally preoccupied with true crime? Because I didn’t binge-listen to Anne Rule to learn red flags, and I never turned into an armchair detective.

So was it out of morbid voyeurism? Was I the audience Uncensored Detective was aiming for?

Or was it a counter-note to all those whodunits? A reminder that real crime is never so neatly structured, and rarely wrapped by the third act?

Honestly, I still don’t know.

And there’s a reason I use the past tense when talking about my consumption of true crime. After that mid-2010s binge, I seem to have lost my taste for it. Nowadays, my audiobooks are mostly autobiographies and I no longer have to turn down my car stereo when I’m at a stoplight (if you know, you know). Nowadays the murders I consume (at least outside the news) are all fictional.

Maybe my turn away from true crime can be blamed on the pandemic. Maybe there was enough tragedy spreading throughout the world that I didn’t need to go searching for it.

Or it could be that I started writing the Pentecost & Parker series. That I started thinking about murder for a living.

Except, that’s not really true. In fiction, as in real life, a murder only takes a moment.

When I break it down, as a writer I don’t think about murder much at all. I think about the aftermath. About the victims and the holes left by their absences. Especially when I’ve got Lillian Pentecost at the helm, whose personal ethos is to always center the victim.

Which, now that I think about it, is almost certainly something that was inspired by that fling with true crime. Maybe not from the books or podcasts themselves, but from the conversation around them. Is there a more thoughtful way of creating a murder? One that still has the structure and the whodunit and the tropes and the trappings, but doesn’t ignore the trauma, or pretend that the world is set right when a killer is caught.

My love of fictional murders helped me get through childhood. And my love of real ones, however brief, is helping me create new fictional murders that, hopefully, will help others in the same way.

Now that I type it, that sounds a little too neat. Which probably means I’m making it up.

But, I think, it might be true.

***