Do you enjoy mysteries with real historical figures as the amateur detective? I love learning about history while I’m tearing through the pages of a good mystery. It makes me feel virtuous and adds to the mystery as I speculate on which aspects are real or fictional. I always end up searching the internet or going to the library to learn more.

When I had the chance to write a mystery series with Eleanor Roosevelt as the detective, I knew only that she was a former First Lady of the United States and an advocate for equality and human rights. As I jumped into research, I learned the real woman was all that and more.

Eleanor Roosevelt wrote four volumes of her autobiography and My Day, a national syndicated newspaper column that ran six days a week and was published in 90 newspapers across the United States at its peak of popularity. While this provides much information about her life, weaving a fictional mystery around her real schedule proved a challenge. I knew I couldn’t be completely accurate, but I wanted the story to be credible—perhaps a murder could have happened, and Eleanor fit an investigation around her packed timetable.

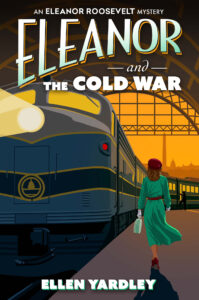

ER, as she was known to match her husband’s FDR, left the White House in 1945 after the death of her husband. Famously, as she was leaving, she said to Harry Truman, who had taken over the presidency, “Is there anything we can do for you? For you are the one in trouble now.” I set my first book, Eleanor and the Cold War, in 1951, while ER was a delegate to the United Nations. President Truman offered her the position, to begin in 1946. Eleanor first considered declining. How could she be a delegate to organize the United Nations when she had no experience in international meetings? She accepted at last, in “fear and trembling.”

Toting her luggage and typewriter case by herself since no one told her she could take a secretary, Eleanor boarded the Queen Elizabeth to sail across the Atlantic Ocean. Faced with incomprehensible State Department papers (in her autobiography, Eleanor wrote she would find it hard to reveal any Department of State secrets because she was seldom sure of the exact meaning of what was on the blue sheets) and discrimination against her gender, Eleanor stated that she walked on eggs. She was the only woman on the delegation and feared that if she failed to be useful, it would be considered that all women had failed.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s days began before eight o’clock, when she met with advisors for breakfast, and ended after midnight with informal meetings with delegates in her room and work on her correspondence. Even though she felt inexperienced, she verbally sparred with Soviet-era politicians as her committee developed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Eleanor writes that she interrupted the Soviet delegate, Dr. Pavlov, in his attack on the United States to state, “Sir, I believe you are hitting below the belt.”

There is no doubt she was a remarkable woman. But what makes Eleanor Roosevelt a great amateur detective?

A good detective understands people and their complex motives. In her autobiography, Eleanor writes, “Very early, I became conscious of the fact that there were people around me who suffered in one way or another.” At six years of age, she helped her father serve Thanksgiving dinner at a newsboys’ club and learned that many of the “ragged little boys” had no homes. She developed compassion for people in all walks of life.

Born in 1884, Eleanor lost her mother to diphtheria when she was 8 and her father to the disease of alcoholism when she was 10. Her mother, a beauty, called young Eleanor “Granny” because she was serious and plain, while Eleanor wanted to sink through the floor in shame. Eleanor blossomed when she was sent away to England to attend Allenswood school, and found her voice and confidence under the tutelage of Mlle. Souvestre. I believe her awkward beginning taught her empathy for individuals. This served her well as she toured through the U.S. during the Great Depression as FDR’s eyes and ears. For me, her empathy was an important aspect of Eleanor Roosevelt as a detective.

I believe an amateur detective should possess a strong moral compass. Eleanor left DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) when that organization refused to let the famous contralto Marion Anderson, a Black woman, sing in their hall. In another instance, when Eleanor was told she must sit in the white section at a meeting, she deliberately placed her chair in the aisle between the two segregated sections. Eleanor championed human rights. I believed that she would also be driven to right injustices, which is the perfect motivation to investigate murder.

The most surprising thing I learned about Eleanor Roosevelt was how she celebrated after the ratification of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. What she did revealed her fascinating personality and, to me, showed she had the main quality that makes a great amateur sleuth.

On Eleanor Roosevelt’s first day of United Nations meetings at the Palais des Nations chambers, she marveled at the entrance lobby—soaring ceilings over acres of polished marble floors. As she went in, she whispered to a State Department advisor, “I’d love to slide on those floors.” After the draft declaration was voted in, Eleanor walked out of the meeting room with a colleague and a Russian representative. She stopped where the hallway opened out to the entrance hall. Her colleague told her, “You can now take your slide.” And Eleanor slid across the marble.

The image of Eleanor Roosevelt playfully and joyously taking a running slide across the marble floor fascinated me. I knew she would make the perfect detective: she possessed joie de vivre, curiosity, and a rebellious, honest heart that led her to break a few rules.

***