Over the course of the pandemic, we (the royal, anxious, self-isolated we) watched a lot of horror movies. More than usual. In fact, Contagion, Steven Soderbergh’s chilling pandemic thriller from 2011 was one of the most streamed movies of 2020. This data generated a few headlines of course, because why on earth would we (the collectively sad and terrified we) want to micro-dose on fear in the middle of a waking nightmare?

There’s a thing that people say—usually to themselves just before a rectal exam, but also sometimes to other people going through a tough time: the best way out is always through. Meaning, among other things, that life’s challenges can’t be avoided, only faced, endured, and mined for lessons (clench less next time).

Perhaps, by binging horror fictions, we’ve actually been training—bolstering our brains against the mental anguish of the pandemic, prepping for whatever else the decade has in store. Consider the experience of watching a horror movie: you’re hyper-focused, present with the television, your mind hooked by a tight leash to the film’s threat. You’re stressed, sure, but as opposed to anxiety’s relentless spiral, this stress is directed. And there’s a cap to it. You’re not actually scared that Samara from The Ring is going to crawl all jittering pixels and pointy elbows out of your TV screen. Your sympathetic nervous system responds as though she is, activating the involuntary processes of the fight or flight response—increased heartrate, raised blood pressure—but in your heart of hearts you know she’s not. You know that you’re safe and sound in your living room. And that you haven’t had a landline in a decade. Enter the parasympathetic nervous system, which facilitates the rest and digest response—lowering blood pressure, decreasing heart rate, letting your body know that it’s okay—and what you have is a challenge faced, endured, and mined for lessons.

This theory aligns with the outcomes of a recently published study, which asked over 300 participants about their entertainment preferences, and their emotional state during the pandemic. The study found that “voluntary use of horror entertainment may lead to less reliance on avoidance mechanisms in response to fear…by eliciting fear in a safe setting, horror fiction presents an opportunity for audiences to hone their emotion regulation skills…which have, in turn, been shown to be associated with increased psychological resilience.”

In other words, as the legendary Wes Craven once put it, “horror films don’t create fear, they release it.”

But I suspect there’s even more to it than that. The experience of anxiety and depression exist so far beyond language that only metaphor can begin to adequately describe it. Horror gives a face to the monsters which lurk in our own minds. The Babadook is grief. The Yellow Wallpaper is postpartum depression. To see these depicted on screen or in print, is to know, on some level, (a level which might sometimes be buried beneath an inky thick of hopelessness) that you’re not actually alone. Because another person experienced this awful thing too, and they lived to write about it.

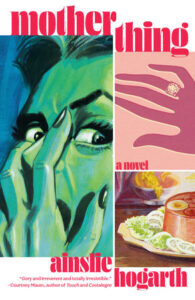

My new novel MOTHERTHING is just such a book—a story about depression, but also, a ghost. Abby Lamb has married the perfect man, Ralph, who is going to give her the perfect life—lots of love and a big family, in a clean, safe home. Exactly what she’s always wanted but never had. When Ralph’s mother, Laura, a cruel woman who Abby tried very hard to love, commits suicide, her ghost returns to terrorize them both: dragging Ralph down into his own suicidal depression, and threatening to destroy all of Abby’s hopes for a better life. With everything on the line, Abby must come up with a chilling plan to rescue Ralph from his tortured mind, and break Laura’s hold on the family for good.

This idea germinated while living with a loved one in the throes of a severe depressive episode. It was a long, difficult process, caring for this body which had seemingly been emptied of its soul. In darker moments I worried, perhaps selfishly, how their illness might be affecting me. Other diseases of the body were easy enough to avoid, contaminated respiratory droplets for example, can be blocked by a fresh face mask. But depression is different. More insidious. So, like everyone who streamed Contagion in 2020, I became very interested in stories of folie a deux, shared madness, a psychiatric syndrome in which delusions are transmitted from one person to another.

The most sensational examples of folie a deux are about couples who murder together. And though that’s not Abby and Ralph’s story, it made me wonder about the extent to which shared madness is a possibility in any close romantic relationship. Maybe even a necessity for close romantic relationships, particularly as we’ve defined romantic relationships for straight women: hopeless devotion, blurred boundaries, implicit trust, the expectation that you and your husband will fulfill one another’s every physical, emotional, and mental need. And so Abby—a lightning rod for all the bad intel passed down to women about marriage and relationships—was born.

And over time, reading all those real-life horror stories about folie a deux was good for my mental health. By engaging with what terrified me, I felt somehow inoculated against it. By the time my loved one began to feel better, I had a first draft finished. And that old adage proved itself to be true once again: the best way out is always through.

***