British crime writing is famed for its grittiness: hard-bitten cops risking all in the war against drugs, gangs, human trafficking and corruption. Favoured backdrops are the high-rise council estates of Glasgow or London’s East End, where it’s entirely realistic that every utterance begins and ends with the f word.

In real life, of course, crime is not restricted to a particular social class. One of the most enduringly fascinating murders in recent British history is that of Lord ‘Lucky’ Lucan, the earl who bludgeoned the family nanny to death on 7 November 1974, before escaping in a borrowed Ford Corsair and disappearing, well, forever. Last Christmas yet another film about the ‘murderous peer’ was aired, in the form of a BBC documentary miniseries.

The most shocking aspect of the crime was not its brutality, nor even that the perpetrator and his pals were British aristocrats, but that it took place at 46 Lower Belgrave Street, in the heart of London’s most expensive residential district. Like Regent’s Park and parts of Kensington, Belgravia is a magnificent architectural set piece: 200 gleaming acres of white stucco and gracious gardens, designed and constructed by Thomas Cubitt between 1830 and 1847. Walking around today, it looks very much as it must have done then (imagine horses and landaus instead of cars) and remains under the draconian control of the family which commissioned it, under the auspices of the Grosvenor Estate.

I have an albeit slender personal connection with the Lucan case – a friend of mine was sent in to babysit Lady Lucan in the days after the murder. Her ladyship – Veronica – would spend the afternoon stretched out on the marital bed, smoking cigarettes and watching TV. ‘Look!’ she’d drawl, eyes wide. ‘We’re famous.’

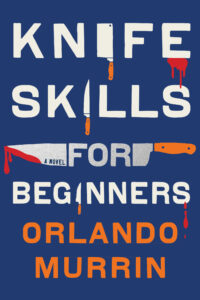

As I’m never likely to live in Belgravia (alas), I thought the next best thing would be to write a story set there, which is how I embarked on my cozy crime debut, Knife Skills For Beginners. Recently bereaved Paul Delamare, a talented chef and food writer, has been left ‘the smallest house in Belgravia’ – a two-up, two-down cottage perched above Sloane Square tube station.

What with estate charges and compulsory maintenance, Paul has to watch every penny, while neighbours – when they’re not on the slopes at Zermatt or sunning themselves on their superyachts – luxuriate in five-storey mansions, complete with swimming pools, home cinemas and underground garages. My story zigzags between Paul’s tiny pad and – in brutal contrast – the faded grandeur of the Chester Square Cookery School, a five-minute walk away, with ten bedrooms and clerestory ballroom.

‘London is famously a city where the socioeconomic picture might change entirely from one end of the street to another,’ declares Alex Hay, historical suspense author, whose two novels, The Housekeepers and The Queen Of Fives, are set in Edwardian Mayfair, across the park from Belgravia. ‘This has always been a place where extreme wealth lives cheek-by-jowl with desperation and poverty.’

It makes sense: rich people need servants – hence the poky mews and service lanes behind the big properties, originally for horses and deliveries, grooms and footmen. And they’re also magnets for robbers and felons: if you’re looking to lift a Bentley or snatch a string of pearls, you won’t find many in Tower Hamlets.

‘For The Queen of Fives I spent a lot of time looking at real-life con-artists of the late nineteenth century – those charlatans and imposters who infiltrated the wealthiest corners of society on both sides of the Atlantic. Really, the extraordinary thing is how much they could get away with. But this was an age of slower communications. False heiresses could operate in plain sight for months before being rumbled.’

‘All is not as it seems’ could equally be a catchline for The Attic at Wilton Place (2023), the story of a hard-up student dazzled by her godmother’s Belgravia lifestyle by C E Rose (the pen name of Caroline England). Rose explains her choice of setting. ‘I walked those silent weirdly silent pavements, took in the beautiful architecture, the pillars, grand doors and basements. I stroked the railings with curious fingers, peered into the panelled windows and thought to myself: what goes on behind those voluptuous drapes? There’ll surely be something dark and forbidden behind the innocent, beautiful façade…’

The Wilton Place townhouse, with its sumptuous drawing rooms and sweeping staircases, is a reflection of the godmother – Vanessa’s – psyche: ‘Elegant and charming, beguiling and full of tempting riches on the outside, but not necessarily the same within. Up in the attic, there’s a hidden room with disturbing secrets, just as there are in Vanessa’s head.’

Previously a divorce lawyer in an affluent part of northern England, Rose has more knowledge than most of the betrayal, controlling behaviour, hidden vices and sexual deviance that can lurk behind apparent respectability. Her latest thriller, The Return of Frankie Whittle (just out), was inspired by a visit to a gated community build on the site of a Victorian workhouse. ‘The silence, the immaculate walkways and identical gardens gave me strong Stepford Wives and other modern horror vibes.’

Another crime series set in Belgravia is by Natasha Cooper, now the crime correspondent for London’s Literary Review. ‘Thirty-odd years ago, while I was writing seriously researched historical novels, I decided to venture into light-hearted crime and came up with a sleuth with a double life. Half the time she was senior civil servant Willow King, despised by her colleagues for her drab clothes and even drabber private life; for the rest of each week she was the ragingly successful romantic novelist Cressida Woodruffe, who lived in a ravishing flat in Belgravia and had a highly satisfactory love life.’ The first of this classic series was published as Festering Lilies in the UK and A Common Death in the US.

Given the opulence and glamour of a Belgravia setting, I wonder if I might be slightly jealous of the people who live there, and by embroiling them in a grisly murder I’m unconsciously punishing them for being wealthy and fortunate. I ask Alex Hay if he feels the same about Edwardian Mayfair: ‘Would I enjoy thundering through those gaslit streets in my expensive brougham, with countless mysteries to solve and a silken top hat in one hand? Well, yes! Yes I would! But I have a feeling that the significant health benefits and sundry comforts of living in modern-day London might outweigh my initial enthusiasm.’

I can see what a strain it places on poor Paul Delamare, dreading another bill arriving in the morning post, so on balance I agree Belgravia is best left to the oligarchs.

***