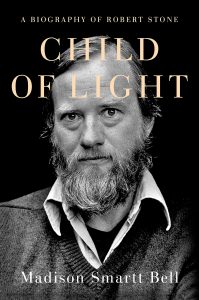

(Excerpted from Child of Light: A Biography of Robert Stone)

The Stones had not been enormously active in the U.K. antiwar movement, although they had marched in one demonstration in Grosvenor Square. Janice’s father, identifying himself squarely with “the silent majority,” wrote them irascibly on the subject: “I don’t mean to hurt your feelings but I know both of you favor the student rebellions and the dissension that is so prevalent in our country today. I believe they are communist-inspired.” Janice briefly sent small sums to sponsor a Vietnamese orphan and gave blood once for a related cause: “Bob teased me that I had donated blood to the Vietcong.” Later on, however, Bob dedicated Dog Soldiers to the Committee of Responsibility, an organization that brought war-wounded Vietnamese children to the United States for treatment (and then repatriated them) and also operated a shelter for children in Saigon.

As the family accountant, Janice was in charge of withholding a percentage of the Stones’ income tax as a protest against the war. Tax resistance (of which Joan Baez was an early popularizer) had been growing since the early 1960s. In 1967, Gerald Walker of The New York Times had organized the Writers and Editors War Tax Protest. By 1970, so many people were involved in tax resistance to the war (usually involving very small sums per individual) that it was not practical to prosecute more than a few. However, Janice’s gesture did inspire an IRS raid on Houghton Mifflin’s Boston office, too late to garnish any payments due to Bob, however, as his contract had run out the previous year. “I was very pleased to hear it,” Janice said, “though it didn’t seem to bode well for our finances.”

Bob’s second novel was going nowhere fast. “I kept running into the Vietnam situation late in the war. I had been away from the United States for a couple of years. I couldn’t get this book written. It seemed to me that these people—my characters—must have been in Vietnam, even though I didn’t know quite who they were. I thought, ‘What is their relationship to this Vietnam situation that is filling everybody’s life now, that is so much on everybody’s mind?’ It’s all anybody could talk about when I was with other Americans. It was so present, looming large in everybody’s consciousness. And I began to wonder suddenly if I couldn’t get some work over there, go and have a look firsthand at what was going on, because it was such an attraction—the idea of Vietnam as a place and as more than a place.” Although the book wasn’t going well at all, Bob’s ambitions for it were quite large, so that “I realized if I wanted to be a ‘definer’ of the American condition, I would have to go to Vietnam. In many ways it changed my life.”

* * *

The Hollywood money was running low, and when Bob decided he absolutely had to go to Vietnam before he could make progress on the book, it didn’t seem affordable to buy a second $500 roundtrip ticket to Saigon, not to mention the point that (as Janice put it), “if I were to go, we would risk orphaning our own children, should anything go wrong.” Bob couldn’t get journalistic accreditation from any established organ of the press, and finally got a card from a start-up (and very short-lived) London publication called INK. At the behest of a friend the Stones had invested $200 in the enterprise, but they were not thrilled with the first issue. “God what a crumby paper it is!” Janice railed to her journal. “The National Mirror was never so bad,” and that was saying a lot. “Every word in it looks untrue—and it’s a left-wing inside-dopester scandal sheet, poorly laid-out,” to boot.

The first issue of INK touched off Bob’s paranoia, always easy enough to provoke. He feared that accreditation would stamp him as a junkie leftist to CIA snoops and Saigon police. So he wrote himself a letter of accreditation on Village Voice stationery, and Mike Zwerin, a European editor of the Voice, obliged him by signing it, though this gesture did not make the credential any less spurious.

The prospect of the trip unnerved Bob to the point that he began spending more time with his children, in the belief he might never see them again. Going to get a visa at the South Vietnamese embassy didn’t soothe his anxiety. A hostile official there was suspicious of him in general and particularly incredulous of the contention that Bob would go to Vietnam to research a novel. Bob came away from this encounter fearful that he might be set up for some bogus bust if he did make the trip.

Bob had been refraining from drink for a bit, perhaps as a sort of training for the trip, but under this stress he fell “off the wagon, with a crash.” Infinitely patient Janice grew exasperated by his dithering. On May 13, his visa came through. The next day he decided he would not go. But in the following few days he and Janice continued to make arrangements for a flight to Saigon and finally bought his ticket for £220. Janice’s diary tracks his vacillation. May 20: “He still says he can’t do it. Wishes he was dead. He’s in very bad shape. . . . He knows it will be nearly as bad if he stays as if he goes. I suspect it may be worse—he may actually have a breakdown.” Saturday, May 22: “He says he won’t know if he’s going until Monday, when he gets drunk and gets on the plane or doesn’t. He says actually he’s going to Vietnam to get killed because he’s impotent. And yesterday I caught myself daydreaming that he was going out there to get recharged mentally and physically, and would come home cured (and thanking me for pushing him out there). But I’m not pushing too hard—I’m afraid to. He might get himself killed for spite, or have a crackup. . . . But I don’t believe for a minute he’s going to die. It’s either Vietnam or a psychiatrist as far as I’m concerned.” Monday, May 24: “Robert has departed.”

Not without trepidation, of course. In parting he told Janice simply: “I hope I see you again.” Janice informed him that she had invoked the spirits of her ancestors to protect him. “Again, as when he went to Mexico, it was as if he had disappeared into a black hole.”

In fact, Bob had checked into Saigon’s Royale, “the hotel of choice of the ‘third-country press,’ meaning many of the European reporters and photographers who were not, as they say, on board.” That style of alienation was congenial enough for him to adopt (and shared by a good number of the American press corps as well). The Continental, where Graham Greene had stayed, was now occupied by a television crew. Bob went there to confer about a possible trip to Cambodia, but if he caught any whiff of Greene’s own special brand of ennui, he didn’t write about it.

Though his flimsy credentials were accepted only by the South Vietnamese Ministry of Information (and not by the American military), Bob soon fell in with a coterie of journalists, whom he described as “all serious war reporters who have paid their dues,” including Gloria Emerson, Dede Donovan, and Judith Coburn. He had a particular admiration for Michael Herr, for the unusual amount of time he spent close to the heavy action of 1968 and 1969. Herr had left Vietnam well before Bob got there, surviving to tell the tale in the enduring form of Dispatches, while others (Sean Flynn, Dana Stone, Larry Burrows, Kent Potter to name a few) were not so lucky. Other journalists kept away from the front lines (not that there were any fixed lines in this guerrilla conflict), did color reporting around Saigon, and imbibed their military information from MACV briefings. The acronym stood for Military Advisory Command, Vietnam, which Bob jocularly personified as a “many-faced, many-armed deity,” which “declared elephants to be enemy agents since they were employed in logistical transport by the NVA and the Front. There ensued what might have been an episode from the Ramayana, in which MACV unleashed enormous deadly flying insects called choppers to destroy his enemies the elephants. Whooping gunners descended on the herd to mow them down with 50 millimeter machine guns, and even my scandalized informant remembers the operation with something like insane exhilaration.”

By Stone and others, the war effort was apt to be portrayed as this kind of darkly comical, epic folly. “They laugh a great deal,” Bob wrote of his colleagues. “There is speculation about the number of reporters who have gotten into smack and talk of acquaintances rightly or wrongly alleged to have habits or who have kicked their habits.” Heroin and marijuana were handily available all over Saigon. Bob had previously tasted smack with Kesey in Oregon (and perhaps also while running the streets of New York in his teens, at a time and place when there was plenty around to be tasted), but the Vietnam trip was probably his first extended fling with the drug, though thanks to his aversion to needles he only snorted, smoked, or possibly drank it on one occasion in “a bar on Tu Do Street, a bar which had the reputation of serving heroin in beer on request.” American soldiers on R&R were equally enthusiastic consumers. “Bands of GIs, many of them hopelessly out of uniform in headbands and Japanese beads, wander around checking it all out. ‘Wow,’ they’re saying. ‘There it is.’ They’re smoking Park Lane cigarettes, which are filtered packaged joints, 600 piastres for 20.” In Bob’s observation, “dope is so pervasive that the language of war has become head shorthand.”

One of his introductions took him to the heart of the expat drug world. “When I arrived in Saigon I had one name to look up. A friend of mine told me you’ve got to look up this guy, so I spent a couple of weeks looking for him, and when I found him I found that he was a junkie, that he lived in a pad on Tu Do Street with a lot of famed journalists, some with Vietnamese girlfriends, and they were dealing in heroin. And also when I located other people that I knew there, nobody wanted to know him, or wanted him anywhere around. And I also discovered that in the hotel where I was staying people were doing a lot of opium smoking. I just generally found myself, as far as I could see, up to my ears in smack.” Some of his discoveries were too outlandish to use. “It is a fact that heroin was smuggled into the United States in corpses, in the coffins of dead soldiers. It seemed to me that this was just too much. . . . The American dead were being sent to Aberdeen, Maryland, with heroin concealed in their coffins. So it’s something that fiction can’t possibly do justice to.

“Stories of the most unimaginably baroque nature came out of the war, and my feeling is you can’t discount any of them.”

“Saigon—it was Babylon. I was seeing incredible things. This guy took me around to these incredible joints, like existentialist caves, full of Vietnamese students, scenes of draft dodgers, cowboys, rooms beyond rooms, wheels within wheels. And everybody was stoned morning, noon and night. It was extraordinary. Stories of the most unimaginably baroque nature came out of the war, and my feeling is you can’t discount any of them.”

Bob wrote color with the best of them, better than most in fact, savoring the ironies of cultural confusion: “rock music is as thoroughly un-Vietnamese as bobsledding or gang rape (which seems to have been another innovation stimulated by the American presence) and watching CBC [a Vietnamese rock band taking its name from the CBC bar in Saigon] one is aware that the process through which a 25-year-old Vietnamese transforms himself into a San Francisco bass player must be extremely dislocating.” Scenes like these (first published in the Guardian, since INK had evaporated, leaving scarcely a stain, by the time Bob got back to London) would make their way into the opening movement of Dog Soldiers. Even in his color reportage, moral nausea sometimes leaked through his lightly satirical tone.

“The previous occupant of my Saigon hotel room apparently had a thing about smashing lizards . . . Since house lizards are useful insectivores, a cheerful friendly presence in every hot country on earth, it is difficult to understand why anyone should want to massacre them in this fashion. So the vision of my faceless predecessor stalking about his Sydney Greenstreet Colonial hotel wasting lizards with a framed tintype of Our Lady of Lourdes (on evidence, the hunter’s instrument) is a disturbing one with which to begin the day.” Later: “in the course of my short walk from the hotel I have seen several lepers, a couple of crippled ARVN soldiers and a begging cretin led by an ancient woman, but it still seems to be the lizards that worry me.

“Lights ash in my eyes—the carefully nurtured outraged humanism I brought with me seems to have stalled at ‘Reptiles.’ . . . My fever is coming back, the low-grade fever I’ve been nursing for several days, along with that outraged humanism.”

Bob collected bitterly telling anecdotes: The Great Elephant Stomp, the active-duty, uniformed ARVN soldier pretending to be blind to facilitate his begging. Tipped by Judith Coburn, he visited the scene of a bombed tax office (which Coburn had witnessed from a restaurant across the street). “Nearby buildings have their windows broken and there are still a few shards of dishware and the odd spoon lying around among the chips of concrete. The street seems to smell of Clorox. Here and there are sprinklings of dried white powder that someone says is chloride of lime and on one wall a brown smear that appears to be a washed-over bloodstain.”

On one occasion Bob did get closer to the action, “by motorcycle with another journalist,” by Janice’s recollection, “and he scared himself quite a bit.” The other man was a buddy Bob wrote about “under the name of Harry Lime . . . for so long I can’t remember his actual name.” They rode along the outskirts of Operation Dewey Canyon II, in which U.S. troops supported an incursion of South Vietnamese troops into Laos—the ultimate goal was to interdict the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This outing was sufficiently dangerous, and Bob got a glimpse of what in his later writings on war he’d call “the elephant,” “going to see the elephant” having been an American Civil War expression for a green soldier’s first experience of combat. It was not something he talked or wrote about directly (though John Converse’s experience under fire in Dog Soldiers probably runs very close to Bob’s own).

Even twenty years later, writing for Esquire, Bob remained elliptical about it: “When I had finished my business in Saigon, I seemed to feel, for reasons that now strike me as idiotic, that honor required my reparation to a point in-country where ordnance of some sort might be discharged in my general direction.

“Off I went, to a place whose name I’ve forgotten; I think it was about thirty kilometers northwest of Saigon. A grunt who briefly traveled with me expressed the hope that since I professed a moral responsibility to be shot at (or at least near), I might find it in me to get my ass killed outright. This was the fate he found suitable for the sort of people who were in Vietnam when they didn’t have to be.”

If the trip to a live-combat zone was unnerving, civilian life in Vietnam could be even more so. “I did get to know far more than I wanted to know about the Saigon underworld. I found that scene thoroughly scary—so scary that sometimes I felt safer when I went out toward the line than I did in Saigon.”

“It was the spring of 1971,” Bob wrote, decades later; “the war was lost. I had just taught my kids, in London, to ride their two-wheel bicycles. I didn’t want to be there, in Vietnam; I didn’t want to stay. I didn’t want to leave, either, because it seemed betrayal.” His experience in the navy gave him a sense of solidarity with the American combat grunts in Vietnam, while he also sympathized with the antiwar sentiment common in the press corps to which he now belonged (and indeed there was plenty of antiwar sentiment among the combat grunts too). On his way back to London from Saigon, he stopped in Thailand and spent a night in the Buddhist monastery at Ayutthaya, where he “obtained and drank a bottle of Mekong whiskey.

“‘Weakness of the strong man,’ the chief monk said merrily as he prodded me awake . . .

“‘There it is,’ I said. Who knew what I meant by that? It was what everybody said in Vietnam when they thought they had glimpsed the dark antic spirit of the war.”

Inscrutable, ineffable, irreducible, the expression stayed with Bob for a very long time. Back in London, he used it as the closer for his piece in The Guardian on the tax-office bombing. “There it is. A marginal incident represented by a day-old bloodstain. I stand in the street, getting in the way of pedestrians—the thoughtful tourist trying to draw a moral. But there isn’t any moral, it makes no sense at all. It reminds me of the lizards smashed on the hotel wall.”