To be honest, there’s something deeply wrong with those of us who choose to write murder mysteries and crime fiction. The things we put our characters through is appalling. Our choice of genre borders on sociopathy.

Which, I suspect, is why some of the best crime novels also are pretty funny.

Murder and mayhem are tough stuff to write about. Unless your goal is to frighten the reader—and yes, there are some awesome thrillers that do just that, with no hint of humor—then you’ve gotta do something to leaven the topic.

Besides, “violent” and “funny” blend for the same reason “sweet” and “salty” do. They provide contrast and depth.

This is nothing new. Donald Westlake was blending crime and comedy back in the 1960s. The first book I read featuring John Archibald Dortmunder was The Hot Rock (1970). I remember thinking: I can’t be laughing out loud at these guys. They’re criminals. And yet….

Gregory McDonald and 1974’s Fletch was terrific. (Guy in a black suit and shades: “We’re CIA.” Fletch: “How do you spell that?”)

The master would be Elmore Leonard. Pick a book. Any of them. Great mysteries and great humor, with sparse dialogue. The dude’s the master; no question. Perhaps my favorite scene of his: 1974’s 52 Pickup, in which thieves hijack a tour bus in Detroit and start showing the tourists their version of Motor City, pointing out bordellos and illegal drinking joints. Those boarded-up buildings to the left? “Historic remains of the riot we had a few years ago.”

This isn’t a set-up, a punch-line and a rim-shot. This is humor found in everyday experiences of people on the fringes of society.

(Anyone else notice that I seem stuck in the 1970s here?)

Tastes differ. If you’re a fan of the comedy novel that happens to have a mystery or thriller story element, Kyra Davis—Sex, Murder and a Double Latte—is killing it (sorry).

Others prefer mysteries and thrillers that employ comedy as a storytelling element.

Robert Crais, creator of Elvis Cole and Joe Pike, has been blending violent and funny in a perfect ragout for decades now, including his most recent, 2019’s A Dangerous Man. The reason his books work is because first and foremost, they have terrific plots. Secondly, they have terrific characters. Then he adds the funny. For Crais, funny is cilantro. It’s not the body of the dish, but it sure adds to the flavor.

Another element of Crais’s genius, I think, is this: Elvis is funny, sure, but Pike has no sense of humor whatsoever. Putting a completely humorless guy in funny scenes works for the same reason the Marx Brothers kept putting Margaret Dumont in their movies as the society doyenne. (From everything I’ve read, she never understood why the jokes were funny, so the brothers insisted on casting her in, like, seven films. And they remain comedy gold today.)

We don’t think of Lee Child as a funny writer, because the Reacher novels—while terrific—are pretty straight-forward mystery thrillers. The humor’s there, but Child never went for the belly laugh. He went for the wry smile. I’m thinking of his 2011 novella, Second Son, in which we meet his bad-ass protagonist as a teenager living on a military base in Okinawa with his family. The teens on the base are cowed by a big brute of a kid and his loyal gang of bullies. Right up until Reacher wraps a couple yards of wire around his fist, lets the much bigger kid come for him, and clocks him. He then turns to the rest of the gang. “Next… Anyone…? OK. Let’s all get it straight. From now on, it is what it is,” and then walks back into his house. Bully problem solved for good.

Again: It isn’t thigh-slapper of a joke. It’s just satisfyingly offbeat.

There are writers who only turn funny when they feel like it. Gar Anthony Haywood’s Aaron Gunner series is pretty grim; then he threw us a curveball with his exceedingly funny Man Eater.

Also: Check out Oyinkan Braithwaite’s My Sister, the Serial Killer. It’s awesome and surprisingly funny given the topic.

Some writers lean a lot stronger into the funny, and if they’re good enough, they can get away with it. I’m thinking Carl Hiaasen or Janet Evanovich. Hiaasen comes out of journalism, just as I do. And nobody has ever skewered Florida as well as he does. (Sorry, Sunshine State: It’s a longstanding meme in newsrooms to collect headlines that begin with “Florida man…” and end with some absolutely insane crime.) From 1986’s Tourist Season through 2020’s Squeeze Me, Hiaasen has been clobbering his home state in much the same way that anvils clobber coyotes.

Evanovich started with Hero at Large in 1980 but she’s best known for the Stephanie Plum series, which began with 1994’s One for the Money and runs through 2019’s Twisted Twenty-Six. Evanovich is nothing if not prolific.

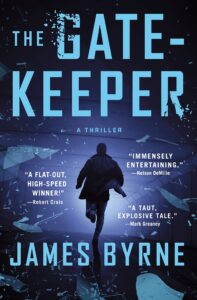

In The Gatekeeper, I challenged myself to come up with a mystery thriller and to play the humor big. It’s a tough needle to thread. When I began creating the protagonist, Desmond Aloysius Limerick, or Dez, he went through a whole lot of iterations. He was an American. He was in his fifties. He was a Marine, then a cop, then a criminal. Then he was none of those things. He was laconic until he wasn’t. (Comedy aside: In my newsroom, I once describe a guy as laconic and my sports editor said, “Laconic? Does that mean he can’t drink milk?” Totally not making that up.)

What I ended up with was an action hero in an action plot who’s basically the happiest guy in the world, loving his life, taking very little—especially himself—seriously. My favorite element of Dez is that, when offered sex, he’s instantly fifteen years old. (“Sex? God, that’d be brilliant! Yeah, please!” He’s the polar opposite of cool.)

I’d read enough great thriller novels with brooding heroes, and figured I couldn’t beat Gregg Hurwitz or Mark Greaney (those guys are awesome) at that game. So I’d have to try something entirely different.

I tried to put the laughter in slaughter.

***