I’ve always been drawn to American crime fiction.

My gateway drug was Thomas Harris’s sublime Red Dragon. I read it as a young boy, and it opened my eyes to the sort of stories fiction could tell. I struggled to fully let it go; a part of it, I think, remains lodged in my brain, tainting anything I try to write with its wonderful darkness. The simple concept of this dreadful killer roaming the vast country and the tortured detective hunting him down was unlike anything I’d read at that point; a story that somehow felt both elevated and yet more introspective at the same time.

Looking back over some of my favourites of the genre—the James Ellroys, the Gillian Flynns, the True Detectives—I’ve tried to work out what it is about these US-set stories that I love so much.

I think some of the attraction comes from the setting, or at least the sheer variety of it on offer. America is a colossal smorgasbord of environments. A buffet of bustling cities and small towns, of arid lands and frozen wastes, of mountainous peaks and rolling plains. This vast array of possible settings has a direct influence on the types of stories you can tell. You can dive into the gritty workings of an inner-city, with all the bureaucracy and dogmas that come with it. Or you can dump a couple of detectives in the back end of nowhere, without back up or oversight, and drag them through sheer bloody hell. You can write a pacey police procedural or you can write a horror. There’s a range of stories in American crime fiction that I don’t see anywhere else, and I think it must come—at least in part—from the array of environments it has to offer.

Take Michael Connelly’s incredible Bosch series of books, set in the tangled web of Los Angeles and filled with the politics of career detectives— take that and compare it to something like Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men. McCarthy’s book is so simple it’s almost barebones; a cat-and-mouse chase across the open deserts of West Texas. Both crime stories, both completely different, both entangled with their setting to such a degree that it becomes like a character all of its own.

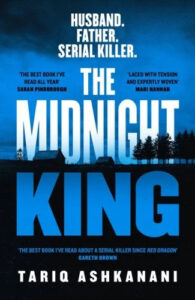

When writing my latest book, The Midnight King, I knew I wanted to set it in a US city. Too scared to try New York or LA—cities that have been done so well before and by people who know them far better—I quickly settled on Nashville. It’s a place I’ve been to a couple times before and am absolutely in love with. The music, the food, the atmosphere; it’s such a wonderful, welcoming place, and somewhere that I’ve never really seen a dark story set before. The draw of writing a murky, murderous serial killer novel and placing it in such a happy, vibrant city was a contradiction too good to ignore.

I suspect part of my fascination with US crime fiction also comes from the way I write. I’m a very visual writer, and when I’m doing a scene or trying to plot out an arc, I picture it in my head as something akin to a film scene. I love leaning into dialogue and letting that do the heavy lifting— both in moving the plot forward and revealing character. I try to write scenes the way they might be portrayed in a screenplay. I know the great advantage of a novel is the ability to dive into your characters’ heads and put their innermost thoughts down on the page, and of course I do that, but honestly I love seeing them come to life organically: through their actions, their speech, their interplay with others.

My touchstones here are in film and TV, and again they are almost overwhelmingly American. Things like True Detective, Seven, and Hell or High Water. It helps that many of my favorite books have been adapted for the screen—Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects, James Ellroy’s LA Confidential, Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. I love comparing the books to their film and TV counterparts, analyzing how they were changed, how they were broken down and—in some cases—how they were improved.

When I compare UK crime fiction to its US counterparts, I find the biggest differences are nearly always in the focus of the protagonists. Here in the UK, we love a police procedural. We love diving into the inner workings of an investigation, into the bureaucracy and the various ranks of the officers involved. There is a great pride in the accuracy of the depiction (and legions of readers who will spot any mistake). By and large, my experience of US crime fiction has been quite different. Often the detectives will operate by themselves, or with little oversight from a superior. There is more variety in the stories being told, perhaps even a willingness to push against boundaries and merge genres in a way that the UK seems reluctant. Personally, when it comes to the great ‘authenticity versus accuracy’ debate, I find myself firmly on the former; I’m never too fussed about whether or not something is true, so long as it feels true. There is freedom in being able to play a little fast and loose with the rules, a recurring motif that I find predominantly in US fiction.

Writing about America is useful in other, less obvious ways too. The great age of the serial killer—that period during the 70s and 80s before DNA evidence existed—gives us a multitude of terrifying characters to base stories on. People like the Night Stalker, the Zodiac, the Golden State Killer. All truly horrifying, all deep chasms of inspiration for stories, and all American.

These killers served as perfect inspiration for my own—Lucas Cole, aka The Midnight King. A sadistic psychopath who has strangled at least thirteen children whilst maintaining the public persona of a quiet, pleasant family man. Could someone like Lucas Cole have existed only in America? I’m sure the answer is no—people such as Peter Sutcliffe, Fred and Rosemary West or Myra Hindley and Ian Brady show that evil exists in all corners of the world. And yet there is something intrinsic about serial killers and America. There is a connection there, one likely reinforced by decades of Hollywood movies and documentaries, but a connection nonetheless.

The vast landscape of America also lends itself nicely to that other facet of US crime fiction—the vigilante. People take the law into their own hands no matter where they live, but the character of a PI is again something that I think is uniquely suited to the US. I love a detective-like character, but sometimes you want to move even further away from the confines of working for a police department. A PI lets you break the rules a little more, it lets you put an everyman in over their heads and watch them scrabble to get clear. That was how I saw the character of Isaac Holloway, the PI who is hired to track down one of Lucas Cole’s still-missing victims. Someone who butted heads with the detectives working the case, who was forced to act outside the law to get to the truth.

Of course, it’s also impossible to write truthfully about America without addressing the reality of America. A country that now seems more divided than ever, more troubled, more insular. And sure, the UK has gone through its fair share of division these past few years, through referendums and the steady churn of political leaders, but watching America from afar at the moment is something akin to a car crash in slow motion. It’s ugly and terrifying and impossible to look away from. And so surely now, more than ever, is the time to explore, to use all the trappings of the genre to dive into what America is. A much better writer than me once said that crime fiction was a lens through which people viewed society, and I think that’s perhaps its greatest gift. It allows you to examine and pass commentary on the current state of the world. The Wire is the obvious sublime example; a show that used each of its five seasons to painstakingly pick apart a social topic and to lay bare the reality of the arguments used by both sides.

America is a complex, contrasting, challenging place. In setting, in beliefs, in history. It has given us some of the most wonderful, inspiring stories, and some of the worst of humanity. It is both unmoving and ever changing. For writers drawn to the darkness, to the horror, to the fear, it is a perfect place to hunt.

After all, fear—to quote the wonderful Red Dragon—is simply the price of imagination.

***