The 8:04 is coming down the tracks.

Board at your own risk.

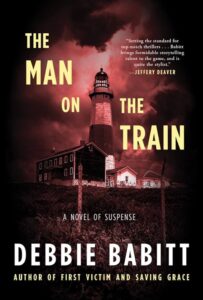

This is the warning on the cover reveal for my new thriller The Man on the Train.

Ever since the original damsel in distress was tied to the railroad tracks and early audiences purportedly fled in terror at the sight of the locomotive roaring into the station in an 1895 silent short by the Lumière brothers, filmmakers and novelists have explored the thrilling possibilities of this singular form of travel.

What makes trains so irresistible to suspense auteurs? Because of their confined, claustrophobic interiors that force strangers into intimate proximity with few places to hide and no means of escape? The fact that they’re constantly in motion, hurtling through time and space across borders and treacherous terrain where neither the passengers nor the audience can get off?

We hear it before we see it, a shrill, piercing sound that sets our adrenaline pumping, especially when it starts out as a human shriek and morphs into a train whistle in The 39 Steps, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1935 tale of international intrigue.

Then suddenly there it is, lumbering into sight. Which means you’ll have to move with lightning speed if you’re the villain preparing to push your unwitting victim onto the tracks. Or it can be a deceptively ordinary arrival, as the Metro North pulls into the Scarsdale station where my married protagonist Guy Kingship waits with his fellow commuters for the doors to open. Then it’s every man and woman for themselves as they race aboard to snag that coveted aisle or window seat. But Guy’s everyday train ride into Manhattan becomes a journey with an unexpected stop in the past he has buried deep when a beautiful woman takes the empty seat next to him.

Speaking of seats on trains, in Hitchcock’s 1941 paranoid thriller Suspicion, based on the novel Before the Fact, the heroine (portrayed by Joan Fontaine) is happily ensconced in her first-class compartment when handsome stranger Cary Grant enters and arouses her suspicions by presenting a third-class ticket to the conductor.

The Master of Suspense’s love affair with locomotives included 1941’s Shadow of a Doubt, which opens at a train station with Teresa Wright’s character eagerly awaiting the arrival of her favorite uncle and namesake Charlie, portrayed by Joseph Cotten. The action climaxes with the story’s antagonist plunging to his death into the path of an oncoming train.

In the 1945 film Spellbound, it’s the layout of the tracks that evokes a plot-advancing flashback in amnesiac Gregory Peck while train-bound with psychoanalyst Ingrid Bergman.

Our first glimpse of the thief played by Tippi Hedren (and that infamous yellow pocketbook) in 1964’s Marnie is from the back as she walks briskly across the platform to await her train.

Cary Grant meets another beautiful woman on a train in the 1959 cross-country thriller North by Northwest, which leaves the after-story to the viewer’s imagination as it concludes with Grant and Eva Marie Saint on a sleeper train about to enter a tunnel.

The Lady Vanishes, adapted from the aptly titled novel The Wheel Spins, was Hitch’s only film with the action set almost entirely on a train. This 1938 spy classic, shot on a ninety-foot set in a London film studio, brilliantly captures the sense of confinement ideal for attempting to conceal sinister doings (including a scene in a baggage car) in the story of an elderly woman who disappears aboard a European express where everyone denies having seen her.

With a screenplay co-written by Raymond Chandler and based on Patricia Highsmith’s novel, the seminal 1951 Strangers on a Train delivers first-class chills. Although little of the film’s action actually takes place on a train, who can forget the fateful in-transit encounter between Farley Granger’s Guy Haines and Robert Walker’s Bruno Antony, the charming psychopath who suggests they swap murders?

Nowhere is premeditated evil more on display than during the train sequence in Billy Wilder’s 1944 film noir Double Indemnity, as Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray carry out an ingenious plan for disposing of the body of Stanwyck’s dead husband.

What about the trains that bear witness to crimes real or imagined?

The recovering alcoholic heroine in Paula Hawkins’s 2015 The Girl on the Train sees something shocking taking place in the backyard of a house she passes on her daily commute to London. Another Lady on the Train was portrayed by musical star Deanne Durbin in the 1945 film about a San Francisco debutante on a New York-bound train who looks up from her book just in time to watch a murder being committed in a nearby building. In Agatha Christie’s 1957 mystery 4:50 from Paddington, Mrs. McGillicuddy is en route to visit her friend Jane Marple when her train passes another train speeding along in the same direction, where a man appears to be strangling his intended victim.

Unreliable narrators or eyewitnesses to brutal acts of violence?

Trains run by timetable, and this strict adherence to schedules heightens suspense and the feeling of impending danger. The action can turn into a furious race against the clock, which happens in the climactic moments of The Man on the Train when Guy Kingship’s attorney wife Linda rushes to prevent a murder with only minutes to spare.

Transcontinental journeys add a sense of the exotic and the unknown.

Christie’s 1934 masterpiece Murder on the Orient Express, written during the UK’s Golden Age of Steam Travel and made into two feature films, is the quintessential train tale because all the action takes place on the fabled luxury liner as it wends its way from Istanbul to Paris. In a setting where physical movement is limited, you can’t commit murder and flee the scene unless you want to risk your life jumping off a speeding locomotive. Even if you happen to be seen, your appearance arouses little suspicion because you are not out of place. You are who and where you’re supposed to be: an anonymous passenger on a train. But nothing and no one is what they seem as the Queen of Crime subverts expectations and the train becomes a repository for the characters’ vengeful secrets and a place of sudden, violent death. Now it’s up to Hercule Poirot, confronted with the most challenging case of his career, to use his little grey cells to deduce the killer’s identity.

Here are a few more films that feature some form of train in the title:

The Sleeping Car Murders, a 1965 Costas Gravas noir film about a woman found strangled in her berth based on Sebastien Japrisot’s novel 10:30 from Marseilles reminiscent of Murder on the Orient Express; the eponymous 1929 film The Flying Scotsman, believed to be the most iconic train in British railway history; Boxcar Bertha (1972), Martin Scorcese’s second feature film; The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, the 1974 film about a subway train taken hostage; Bong joon-ho’s 2013 film Snowpiercer, based on the 1982 graphic novel about earth’s surviving humans living on an enormous train that circumnavigates their glacial planet.

The list goes on.

Maybe now you’re starting to get an idea of why trains make such pitch-perfect suspense and mystery settings. As Federico Fellini said: “Our duty as storytellers is to bring people to the station. There each person will chose his or her own train.”

All aboard!

***