Some real places cry out to be used as thriller settings. When an editor suggested I write a novel about dark doings in a magic library, the first thing that popped into my mind was a memory from my college work-study job, decades earlier.

As an undergraduate at Harvard, I worked part-time in the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library, the flagship of the university’s library system, which houses about 3.5 million books on ten levels of stacks. During my junior and senior years, the library undertook the massive project of digitizing its catalog. Every dusty book had to receive a newfangled barcode, and students like me were dispatched into the bowels of the library to apply them volume by volume.

Sometimes my Widener wanderings led me to subterranean Pusey Library, where overflow was stored. And venturing into that area felt like trekking to the end of the world, or perhaps to the ninth and lowest circle of Dante’s Inferno.

From the touristy parts of Widener—the palatial marble staircases, the high-ceilinged reading room, the bustling circulation area—I slipped through a narrow door into the twilight of the stacks, frequented mainly by bleary-eyed students. From there, I descended four levels to an inconspicuous door in a far corner, which opened into a roar like a wind tunnel.

This was the underground tunnel to Pusey, windowless and adorned only with giant pipes that suggested the belly of an ocean liner. At the end of the passage, I found myself in a streamlined, modern library that felt as disconnected from the outside world as a dream.

To maximize shelf space, most of Pusey’s books were hidden inside towering mobile stacks. You accessed them by pressing a button and waiting for gears to grind, giant shelves to move, and an aisle to open. Signage warned against climbing the shelves. That could deactivate the floor sensors and allow another unwitting patron to close your aisle, crushing you between two merciless units.

As far as I know, no unwary book seeker has ever actually perished in Pusey this way. In May 1995, the Harvard Crimson did report on a professor whose arm was broken by the movable shelves, prompting a safety review. The writer’s lede: “Anyone who has ever used the movable stacks of Pusey Library has probably wondered what would happen if someone actually got caught between the sliding rows of books.”

As a morbid suspense writer in the making, I certainly had. Later, meditating on my magic library book, I decided a gruesomely bookish death in the stacks of Pusey would kick off my plot.

There’s nothing magical about Pusey itself in The Library of Fates. The library of the title is a separate and completely fictional one, though I situated it on the top floor of Boylston Hall, a real classroom building next to Widener.

The Library of Fates is a cozy refuge presided over by imperious librarian Odile Vernet, who has curated it to reflect her personal beliefs about the power of books to shape our lives. Enter the library and ask Odile to bring you the “book you need,” and she’ll produce a volume you find eerily relevant to your circumstances.

Some students say the librarian is a charlatan, playing on the power of suggestion. Others insist the library truly is magic, and the magic emanates from the eighteenth-century Book of Dark Nights hidden in the safe in Odile’s office.

The novel opens in the wake of Odile’s unexpected death. Perusing Pusey’s mobile stacks, the strong-willed, short-statured septuagenarian ignores the warnings and scales the shelves in search of an unreachable volume. The shelves begin to close, not fully crushing Odile—I’ve given Harvard’s current safety measures the benefit of the doubt—but knocking her from her perch and precipitating a fatal heart attack.

It seems like a tragic freak accident—until Odile’s protégée and successor, Eleanor, discovers that the Book of Dark Nights has vanished. Did someone steal the priceless volume? And could the thief have had a hand in Odile’s demise? To find out, Eleanor teams up with Odile’s son to follow a string of cryptic literary clues his mother left for them.

The quest will eventually bring the pair to Pusey Library, but first it takes them all the way to the Latin Quarter of Paris, another storied place where I’ve lived. I considered sending my protagonists to the Eglise Saint Sulpice, like the monk Silas in The Da Vinci Code. But instead I ended up planting their clue in the cellar of the Luxembourg Museum, once a palace of the Ancien Régime.

I mention this because I had no qualms about inventing that cellar out of whole cloth, just as I invented the Library of Fates itself. But when it came to Pusey Library, a strange desire for factual accuracy possessed me. Because I had such vivid memories of my creepy pilgrimages to the far reaches of Widener, I wanted to get the place right.

A trip to Cambridge wasn’t in the cards, so I perused anecdotes online. On Reddit, I confirmed that cellphones get no reception in Pusey and found an invaluable resource. A user sent me their personal video footage of the tunnel, which helped me correct the vagaries of my thirty-plus-year-old memories.

Another find that gave me chills was a 1997 essay from the Harvard Library Bulletin, which appears in Harvard Magazine’s online archives. The late scholar Richard Marius describes the descent from Widener to Pusey in novelistic detail, from the “mysterious alchemy of convection currents” in the tunnel to the dire warnings on the mobile shelves.

He even wrote a sentence that seems to presage my book: “Sometimes I think of writing the Pusey Library Mystery whereby a scholar is found crushed like a waffle between the moving shelves in what seems to be an accident but…to the probing eye of a hard-boiled Harvard scholar…immediately presents itself as murder.”

Though Marius will never be able to read The Library of Fates, I’m glad I wasn’t alone in seeing Pusey’s potential as a setting. I hope I’ve produced a “Pusey Library mystery” worthy of him and everyone else who’s explored this strange pocket of the world-class library.

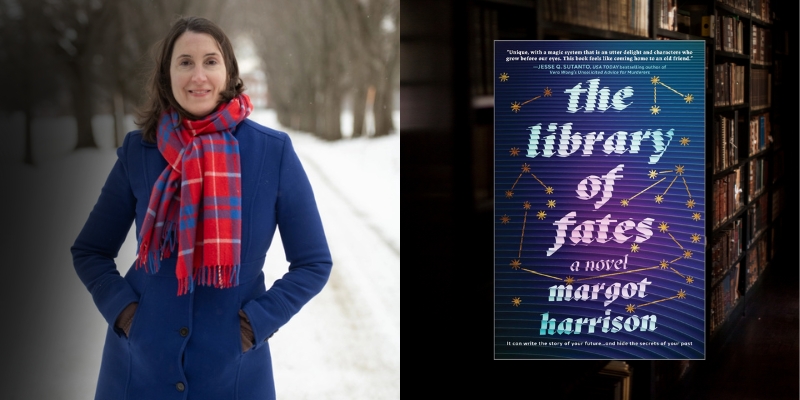

***