It had to be the worst decision of his life. Heinrich Friedrich Albert was sitting comfortably and reading as he traveled uptown on the Sixth Avenue elevated train in New York on the afternoon of July 24, 1915. When he looked up and realized the train was at the 50th Street station and about to move on, he panicked and decided to rush from his seat, yelling to the guard on the platform to hold the door open. That was all he was thinking about—not missing his stop. As he exited the train, however, a woman sitting near him shouted out that he had forgotten his briefcase. He tried to get back into the train but was unable to do so. In the meantime, a man had taken the briefcase and also exited the train. Albert then saw the man carrying the briefcase in the street and chased him along Sixth Avenue. The man jumped onto the running board of a moving, open surface car and informed the conductor that he was being chased by a crazy man who had just caused a disturbance on the elevated train. The conductor told the motorman to keep the car moving past its next stop, leaving a frantic Albert far behind.

Albert, who was the commercial attaché for the German embassy, notified two of his colleagues about the incident. They decided to place an ad in a newspaper offering a reward of $20 for the return of the briefcase and its contents, hoping that the person who took it was just a common thief and, after not finding any money inside, would return it for that meager reward. What they didn’t know at the time was that no amount of money would have resulted in the return of that briefcase. It was now in the hands of the U.S. Secret Service, and the lid was about to be blown off a sophisticated German propaganda, espionage, and sabotage plan inside the United States.

The person who took the briefcase was Frank Burke, a Secret Service agent and leader of an eleven-man special squad that William J. Flynn, chief of the service, had formed to uncover German espionage in America in the years leading up to U.S. entry into World War I. Burke was tailing Albert and didn’t hesitate to grab the briefcase when the German left the train. When Burke showed the contents to his boss, Flynn knew he and his men had struck gold. Inside the briefcase were documents detailing Germany’s nefarious plans in America, including a $27 million budget under Albert’s control to fund pro-German propaganda, attacks on ships carrying war supplies for the Allies, and strikes at the docks and in munitions plants.

Also involved in the espionage and sabotage activities in America were Captain Franz von Papen, the military attaché for the German embassy (and the future chancellor of Germany), and Captain Karl Boy-Ed, the naval attaché. Both were expelled from the United States in December 1915. No official action was taken against Albert, who returned to Germany when America entered the war in April 1917. Exposing the spy ring was a major triumph for Flynn, who was known as “the Bulldog” for his tenacity in pursuing leads. As one newspaper proclaimed, Flynn “probably did more than any one man to rid this country of foreign spies.”

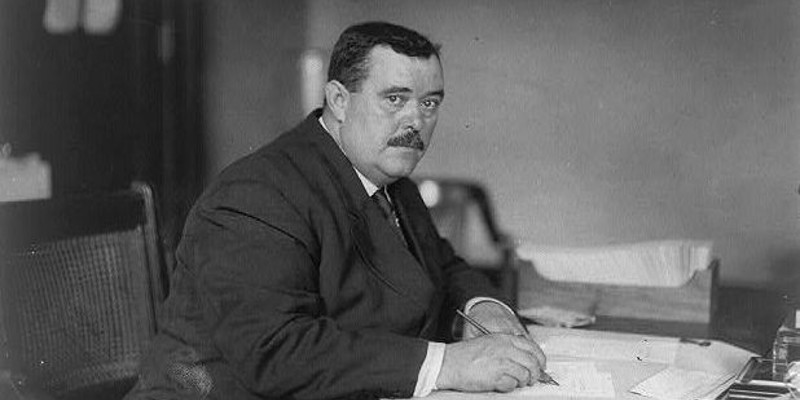

Flynn was a big man. At six feet tall with a cropped mustache and weighing about three hundred pounds, he struck an imposing figure wherever he went. Often in a derby hat, he was once described by a reporter as “large, mountainous almost, up and down as well as circumferentially.” Flynn worked as a plumber, tinsmith, stone carver, and semi-professional baseball player before joining the Secret Service in 1897. He soon rose through the ranks to become one of the most respected and influential detectives and law enforcement officials of that era.

Long before Eliot Ness and the Untouchables went after Al Capone and the Italian mob in Chicago, Flynn dismantled the first Mafia family to exist in America. As head of the Eastern Division of the Secret Service from 1901 until 1910, Flynn pursued the Morello–Lupo gang, who were engaged in murder, extortion, counterfeiting, and other criminal activities both in New York and around the country. He ran an intelligence operation that tracked the movements and activities of Giuseppe “The Clutch Hand” Morello, Ignazio “The Wolf ” Lupo, and other members of the gang for several years, building an airtight counterfeiting case against them that resulted in long prison terms for the mobsters.

The success against the Mafia made Flynn famous, with front-page stories about him in newspapers across the country. The Boston Globe described him as “one of the greatest detectives in the world.” Understanding the value of good publicity for one’s career, Flynn also published first-person accounts of his adventures. While he loved the media attention and benefited from the usually glowing stories about him, Flynn nevertheless played down the image of anybody being a supersleuth like the fictional Sherlock Holmes:

If you want some reading that will put you gently to sleep, try a detective’s record of a sensational case, just as he keeps it: “Interviewed three shoe clerks; no result. Analyst reported poison lotion to be talcum and water. Spent afternoon in subway, endeavoring to locate guard with missing tooth; no result.” And that goes on for weeks and maybe years and still no result, till you have very grave misgivings about the adventures of analytical criminologists and their pale, flexible hands, not to mention their eyes that seem to pierce, etc. No it’s a great bore to be a real detective, when you compare yourself with a super-detective in a novel, growing more super with every chapter.

Flynn’s life, however, was anything but boring. In between his exploits against the Mafia and German spies, he also attempted to end corruption and ineffectiveness in the New York Police Department (NYPD) when he was named deputy police commissioner in 1910. Flynn joined his men in raids on gambling houses, “chasing gamblers up fire escapes and across roofs and dropping down skylights.” Flynn began to reorganize the Detective Bureau to make it more effective and eliminate graft in the police department but was met with opposition from his superiors and entrenched political interests opposed to any reforms within the NYPD. Calling it “a thankless job,” he resigned after just six months and returned to the federal government, where he was promoted to chief of the Secret Service in 1912.

Flynn and his family were targets for revenge from criminals that he put away, including the mob. While in prison, Ignazio Lupo sent out orders to members of his gang who were still free to assassinate Flynn. Giuseppe Morello’s half brothers, Vincenzo, Nicola, and Ciro Terranova, debated a plan to kidnap Flynn’s children. They did not follow through with the kidnapping, but when Flynn learned of this, he told his children to never venture alone more than one hundred yards from their home. Christmastime was a dangerous holiday for the family. Suspicious packages disguised as gifts and addressed to his children and wife would arrive at their home in New York. On one occasion, Flynn started to open a package addressed to him with a return address he was familiar with. But he noticed that something was just not right with the package. He ran outside, put it in the yard, and then got a bucket of water and doused it. He gave it to a Secret Service agent who confirmed that it was a makeshift bomb that would have killed or seriously injured Flynn and his family had it gone off. After that occurred, to the great dismay of Flynn’s children, Secret Service agents dunked every package that arrived at the home in water before they first opened them, thereby ruining any legitimate presents for the children.

Flynn’s exploits against German spies and saboteurs as head of the Secret Service built up his legend and caught the attention of the movie industry. A twenty-part silent movie serial about his adventures was made in 1918 by Wharton Studio, a pioneering film studio based in Ithaca, New York. King Baggot, an international film star and a friend of Flynn’s, played a fictional character patterned after Flynn, who appeared as himself in one of the episodes. Had this been the end of his career, Flynn would have cemented a stellar legacy. Incorruptible, fiercely patriotic, and determined to get results no matter how long it took, he would have left an impressive record of accomplishments that served his country well.

But it was when he took on anarchists and other radicals in 1919 that his career began a downward slide. After anarchists set off bombs in seven cities on the evening of June 2, 1919, including one at the home of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, Flynn was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation (BI), the forerunner of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Palmer, with great fanfare, announced the appointment of Flynn to head the BI and find the perpetrators, calling Flynn “the greatest anarchist expert in the United States.” With these lofty expectations, Flynn faced a difficult task. There was no blueprint to follow on how to organize an investigation into such a sophisticated attack as the June 2 bombings, which had been preceded by a nationwide package bomb attack targeting prominent government officials.

Flynn therefore devised the first counterterrorist strategy and policy in U.S. history. He established a powerful federal police force along with a top-notch team of agents to aid him in the pursuit of anarchists and other radicals in the country. Palmer, though, created a new division in the BI, the Radical Division, and put a young, ambitious former library clerk named J. Edgar Hoover in charge. Hoover soon hijacked Flynn’s investigation and, along with Palmer, orchestrated the infamous Palmer Raids, which involved illegally rounding up, detaining, and in many cases deporting aliens who had committed no crimes. Flynn supported the raids and never spoke up against these violations of civil liberties. Combined with his failure to solve the series of bombings, this tarnished his otherwise stellar reputation.

Flynn had one last chance to redeem himself. After a horse-drawn wagon exploded on Wall Street in September 1920, killing thirty-eight people and injuring hundreds of others in the worst terrorist attack on American soil at that time, Flynn once again tried in vain to find the perpetrators. With no meaningful progress to show from his investigation, he was removed from his post in August 1921 and never again returned to government service.

For Flynn, this was an inglorious end to his distinguished career. He opened a private detective agency a couple of months later and made two of his children, Elmer and Veronica, partners. That was a bad choice, as both were alcoholics and irresponsible, overspending and upsetting clients. Flynn’s wife, Anne, was also an alcoholic who made alcohol in the bathtub of their home for herself and some of their six children when they were of age to drink. The excessive drinking of the family (Flynn mostly abstained from alcohol) and the problems with his detective agency depressed and weakened Flynn, who died of heart failure on October 14, 1928.

Although retirement was not a happy time for him, Flynn did launch one business venture that gave him great joy. In 1924, he edited a new fiction magazine called Flynn’s. To make sure readers knew who was behind this publication, the words “William J. Flynn, Editor, Twenty-Five Years in the U.S. Secret Service” appeared below the title. This gave Flynn a chance to relive his glory days with the Secret Service. While most of the stories were fictionalized, some were based on actual cases that Flynn or his former Secret Service colleagues had worked on. Flynn’s (it would undergo various name changes over the years) became one of the most popular detective magazines of its time. It continued to be published for many years after Flynn’s death.

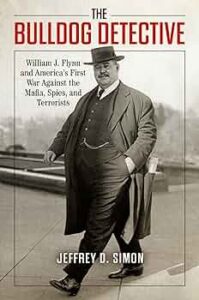

“I might have become a prosperous plumber had I stuck to my shop and original business,” Flynn once told a reporter, “but I’m glad I followed my bent and am now a detective.” Surprisingly, there is no published biography of the man who became one of this country’s greatest detectives by pursuing the Mafia, spies, and terrorists and forged a lasting place for himself in American history. He was at the center of some of the most sensational events of the early twentieth century, and yet today, very few people know his name. This book is the first to tell the fascinating, exciting, and at times tragic story of William J. Flynn. The challenges that he faced more than one hundred years ago still plague America: organized crime, espionage, and terrorism. Understanding how one man tried to tackle these issues and his successes and failures can offer us insight into these endless problems.

___________________________________