As dawn breaks, William Kent Krueger can be found hunched over his notebook at the local coffee shop, fueled by the rising of the sun and the promise of a story.

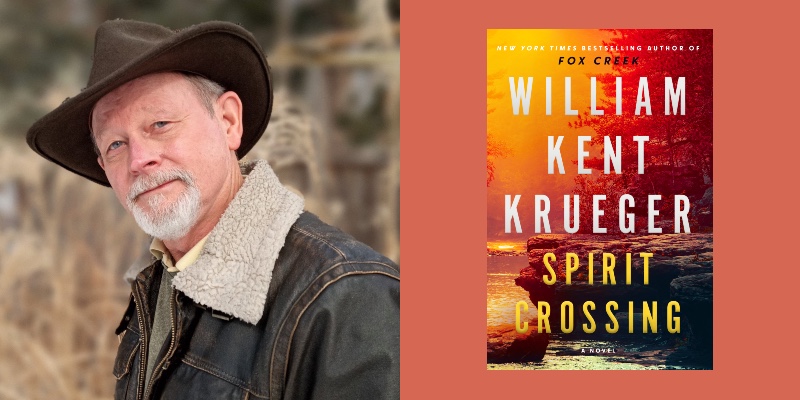

It’s the same routine he’s followed for the entirety of his writing career, from the short fiction of his fledgling younger days to the completion of the twentieth novel in his beloved Cork O’Connor mystery series, Spirit Crossing (August 20, 2024; Atria Books)—and beyond. Despite having achieved the kind of success that most can only imagine—Krueger is the recipient of accolades ranging from the Minnesota Book Award to the Friends of American Writers Prize (not to mention the Anthony, Barry, Dilys, and Edgar Awards) and has had thirteen consecutive New York Times bestsellers—these early morning sessions remind him of a childhood dream, and how he made it come true.

For more than twenty-five years, Cork O’Connor—Aurora, Minnesota’s half-Irish, half-Ojibwe sheriff-turned-PI—has kept the author company, from their debut with Iron Lake through 2025’s as-yet untitled work in progress. (There have been standalones and short stories, also, culminating in sales of more than 1.6 million copies.) As the series and its characters have progressed, so too have the circumstances and crimes within its pages, which range from existential threats against the natural world to the vulnerability of the Native American community. After all, Krueger understands that the potency of fictional stories often resonates more profoundly with readers than the facts that informed them.

In that vein, Spirit Crossing finds O’Connor investigating the murder of a young Ojibwe woman, whose disappearance and death have been overshadowed by that of a teenage girl from a prominent white family. Suspecting a link between the two cases (and others), O’Connor—whose gifted grandson, Waaboo, finds himself the unwitting target of a killer—joins forces with the newly established Iron Lake Ojibwe Tribal Police to seek justice. Meanwhile, his daughter, Annie, has returned home for a family wedding with the intention of revealing a burdensome secret—assuming she lives long enough to tell it as the evil draws near.

Now, William Kent Krueger reflects on this landmark novel and the truths that inspired it …

John B. Valeri: Spirit Crossing marks a milestone in your illustrious career: the 20th(!) Cork O’Connor novel. In what ways do you see this book as celebrating the roots of the series while also maintaining its progressive nature? How does the evolution continue to challenge and motivate you?

William Kent Krueger: Over time, the series has evolved into a family saga of sorts. It’s not just about Cork O’Connor, but also about the growth of everyone in the O’Connor household. I believe that more than any previous novel, Spirit Crossing incorporates the soul of the clan while also highlighting the work, lives, and challenges of each family member individually. That said, it’s also very much in keeping with the elemental traditions of the series. So, it’s a mystery. It’s set in the North Country of Minnesota. It involves issues significant to the Anishinaabe community. And, of course, Henry Meloux plays an important role.

Always the challenge with a long-running series is how to keep it fresh. To my mind, the best way to do this is to offer, book by book, a look at the dynamic process of growth for the characters as they age, as events shape and reshape how they view the world, themselves, and their relationship with one another. That’s what keeps it fresh for me, anyway.

JBV: Here, O’Connor investigates the link between a missing white teenager from a prominent family and the murder of a young Ojibwe woman, which reveals the stark chasm that exists when it comes to the treatment of missing and murdered Indigenous people (particularly women). Tell us about the facts behind the fiction. How can storytelling be a vehicle through which to explore unpalatable societal issues that demand a reckoning?

WKK: Here are some startling statistics: 1) The murder rate for Indigenous women and girls is ten times higher than that of any other ethnicity; 2) Murder is the third leading cause of death for Indigenous women; 3) The Bureau of Indian Affairs estimates there are 4,200 missing and murdered cases that are still unsolved. This is a crisis. As I’ve spoken with my friends in the Native community while researching my novels, this deep, long-term concern regarding Missing and Murdered Indigenous People has been obvious. One thing I’ve come to realize is that facts don’t necessarily move people to action. But a good story that deals truthfully with the issue can often have a more profound impact. When I first considered creating a Cork O’Connor story centered on this issue, I asked my Ojibwe friends what they thought of the idea. To a person, they were supportive. I hope that in writing Spirit Crossing I’ve justified their trust in me.

JBV: One of the complicating factors when it comes to investigating these crimes is the jurisdictional quagmire that exists between law enforcement agencies. How did you endeavor to understand these complexities for the purposes of the book – and what are the real-life implications?

WKK: Before undertaking the writing, I spoke with several folks directly involved in dealing with the convoluted jurisdictional issues—reservation law enforcement, state law enforcement, and federal law enforcement. What I came to understand is that one of the reasons cases involving missing or murdered Native people go unsolved are myriad—lack of communication between agencies, confusion over jurisdictional boundaries, unfamiliarity with pertinent legal imperatives, and sometimes simply an unwillingness, for many reasons, to pursue these cases. What it means for Indian Country is the continued challenge of getting answers to their desperate questions or their pleas for help.

JBV: One of the story’s characters, Chief of the Iron Lake Tribal Police Monte Bonhomme, takes his inspiration from a longtime friend of yours whose adoptive Ojibwe daughter suffered a tragic fate. How did this personal connection allow you to imbue the book with its deep sense of intimacy – and in what ways do you hope the story honors your friend and his daughter?

WKK: Quite a while ago, Monte Fronk shared with me the tragic story of his daughter’s murder. I suppose that played a significant part in my decision to go forward with the project. Monte has shared the story of his daughter, Nada, at many gatherings in the hope of raising awareness of the issue of violence against Native people, particularly women. My hope in creating a piece of fiction with this issue at its heart was that I might be able to open the eyes of what is, essentially, a white reading population, so that they might better understand the life-threatening challenges in being Native American.

JBV: As you acknowledge, you have no Native blood running through your veins. How have you endeavored to capture the Anishinaabeg culture with authenticity and nuance – and what advice would you offer to others seeking to inhabit circumstances other than their own for the purposes of storytelling?

WKK: More than thirty years ago, when I began work on Iron Lake, the first book in my series, I knew almost nothing about the Anishinaabeg. But I was a cultural anthropology major in college, and I began to learn in the way of a scholar, by reading. In the course of my research, I began to meet folks in the Ojibwe community and form relationships that have, over all these years, become important friendships. I rely on my Native friends for their insights, perceptions, and suggestions. Many of the stories in the series have arisen because of issues that my friends have made me aware of. Whenever I complete a manuscript for a new Cork O’Connor story, I give it to at least one—but usually a couple—of my Ojibwe friends to read and vet, so that I haven’t said anything that is untrue or stupid or, most importantly, offensive. I think this is a pretty good guide for approaching a culture that is not your own.

JBV: The narrative also continues personal storylines – Annie’s return home, Stephen’s impending marriage, Waaboo’s developing “gifts” – that sometimes amplify the crime elements and other times provide reprieve from them. In non-spoilery terms, tell us about the evolution of the O’Connor family and how their circumstances underscore the themes you explore throughout the book.

WKK: I believe that we are basically ignorant when it comes to what we understand about existence, about the world we inhabit, physically and spiritually. There is so much more to life than we can understand with our brain. Indigenous people around the world honor the spirit in all things, understand that we are a part of a greater energy than can ever be comprehended. I have heard my Ojibwe friends refer to this as the Great Mystery. So, I often step outside the bounds of normal perception in my stories. In the case of Spirit Crossing, the ability of young Waaboo, Cork’s grandson, to touch life beyond this life puts him and the O’Connors at risk. It’s a plot device—great suspense—but with a nod toward a truth I believe in.

JBV: Spirit Crossing is set against the backdrop of Aurora, Minnesota, where the construction of an oil pipeline threatens the sanctity of the land from which the book derives its title. What do you see as the relationship between place and plot – and how do natural elements, which are constantly under threat of development, enhance the ethereal nature of your stories?

WKK: When I taught writing, I would always teach setting before anything else. So much of a story rises out of a sense of place. Character is shaped by place. Motivation is driven by the circumstances or conflicts inherent in a place. Atmosphere is generated by place. The constant threat to our natural environment here in Minnesota, and it’s true in so many places, is such an easy well to tap for stories in my genre. Not only is it pretty simple to create the conflict that will help drive a story but it also serves as a way of continuing to raise the consciousness of those who are ignorant or ill-informed about the greed that drives these threats to our natural world.

JBV: Leave us with a teaser: What comes next?

WKK: I have one more Cork O’Connor novel under contract. I’d planned to put that one on hold while I worked on a standalone that has been begging me to write it for a long time now. I actually began composing that manuscript. Then, like a bolt of lightning (if you’ll excuse the cliché), a great idea for the next book hit me. I’m at work on that now. The piece doesn’t have a title yet and I won’t give anything away. But, God willing, it should be ready for publication in the fall of 2025.