Monasteries are easier to get away from than to get into. As a young man I tried to get into one but the vocation master, well-trained in such matters, knew as soon as I opened my mouth that I was for this world, not his. He sent me on my way, but I never lost the desire to experience his world of ritual chant followed by hours of profound silence. Since writing is a profession of profound silence requiring intense ritual, I’ve found my own form of monastic life, and my latest hero is a monk. So I’ve got it all, and I’m grateful to that vocation master of long ago who steered me toward the only monastery in which I could be comfortable, the one in my own mind.

Each time I begin a book, the walls of that monastery open. I walk through with trepidation, knowing I’ll be behind them for at least a year, in desperate prayer and meditation. Frequently I’ll want to escape and it should be easy. But the walls remain closed as I plead my case: “It was a bad idea for a book, I shouldn’t be here.” No response. “I should be in Hawaii, drinking a mai tai.”

Recently I’ve been behind the walls with my hero, Brother Tommy Martini. He belongs to the Benedictine order but his reason for being in a monastery comes not from a need for silence but to escape prosecution for a felony. I’m lucky I didn’t become a criminal myself because the small town I grew up in was filled with criminals, some of them friends of mine. Once in childhood when we were discussing what we wanted to be when we grew up, I said the usual – fireman. But my ten-year-old friend said, “I want to find an old lady who’s soft in the head and take her for everything she’s worth.” Twenty years later, he went to jail for exactly that crime. I offer this as an example of the mystery of existence. Had he somehow seen his future lying in wait for him? I didn’t become a fireman but he did become a criminal. Childhood is enchanted but we can’t quite grasp exactly how. If we could, perhaps my friend could have escaped the prison cell that was awaiting him.

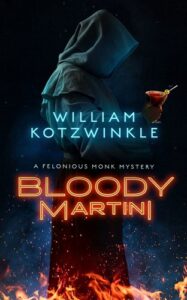

Brother Tommy Martini made his first appearance in Felonious Monk. I took him to glittering Las Vegas, a test for his monastic vow of nonviolence and chastity. In Book 2, Bloody Martini, I take him back to his hometown. I’ve always avoided mine, certain no good awaits me there. But Tommy, with the ghostly ease of a fictional figure, does go, and he visits a place that fascinated me in my youth – a Catholic convent. Many times I walked past its walls imagining sad, beautiful nuns, broken by love and maintaining their vows to never speak to a man, or anyone, again. All they needed to brighten them up was me. That never happened, of course. But in the convent of the mind miracles happen, and with great pleasure I carried Brother Tommy Martini through those forbidding walls. There he walked the quiet gardens, saw veiled faces peering at him through tiny windows. I can’t reveal more, for behind the walls of this convent of the mind is one of the secrets of Bloody Martini.

These days people return to their hometowns through the Internet, contacting lost loves. It’s a dangerous game, for a mysterious glow is cast over those we knew decades ago, and we’re in love before we know it. Class reunions function in the same sinister way; the glow of love saturates entire rooms, threatening marriages while promising the impossible – turning back the clock. So if you’re happily married and an unexpected email arrives, compressing time in a delightful way, I recommend checking into the monastery of the mind.

Sending Brother Tommy as my emissary to the old hometown and letting his fictional form run all the risks for me, I have avoided what happened to an actor friend of mine. He said, “I’ve got to get away from all these drugs in LA. I’m going back to where we grew up.” He learned what Tommy learns, that these days small towns have all the coke you want, courtesy of urban gangs that bring it in. And my actor friend died of a heart attack on a barroom stool in our old hometown.

Brother Tommy checks out these barrooms where the dark spirits hang out. And there are even darker spirits. It’s a coal mining town and beneath the town, mine fires are burning. They’re hard to put out and they burned throughout my childhood. You could walk in certain neighborhoods and feel the heat under your feet. It never failed to impress me but it wasn’t until many years later that I discovered that fiction gives off its own subterranean heat. The minute I started writing about those burning mines, their glow became the presence of evil haunting Coalville.

This quality in the mind, to conjure dark and light, has given birth to the crime and thriller genre. I’m happy to be one of its practitioners.

***